Review Article

Review Article

Addressing Pain in The Oncologic Patient: The Therapeutic Possibilities in The Pharmacological and Interventionist Field

João Lucas Pereira Rodrigues1, Ana Luísa Peireira Rodrigues2, Bruno Belmonte Martineli Gomes3, Eduardo Elias Vieira de Carvalho4, Ana Karina Marques Salge5, Dayana Pousa Siqueira Abrahão6, George Kemil Abdalla6 and Douglas Reis Abdalla6*

1University of Uberaba, Brazil

2University Center of Patos de Minas, Brazil

3University of São Paulo, Brazil

4Federal University of Triângulo Mineiro, Brazil

5Federal University of Goiás

6Faculty of Human Talents - FACTHUS

Douglas Reis Abdalla, Faculty of Human Talents, Uberaba/MG, Brazil.

Received Date: September 10, 2020; Published Date: September 21, 2020

Abstract

Cancer is the second cause of death worldwide, presenting a number of different symptoms, with pain being present in up to 66% of these patients, being characterized as one of the most invalidating symptoms, which may be present regardless of the stage of the disease, either as the first symptom, during diagnosis and treatment or in advanced stages of disease. Thus, this work aims to address the various means of analgesia for cancer patients. Among the approaches are included from the steps established by the pain scale recommended by the World Health Organization, to the approach of interventionist techniques currently in use, giving greater prominence to the use of anesthetics, by different routes of administration (oral, subcutaneous, itratectal, neuroaxial and neuronal blocks), such as safe and effective analgesia for cancer patients.

Keywords: Cancer; Pain; Analgesia

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) states that cancer is the second leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for about 9.6 million deaths, or one in six deaths, in 2018. The National Cancer Institute describes as some of the symptoms of cancer change in breasts, difficulty, pain or blood when urinating, eating problems such as difficulty swallowing, nausea, vomiting, change in appetite, fatigue, fever or night sweating, weight gain or loss without known reason, among others. According to Caraceni [1], pain in the oncologic population is one of the most invalidating symptoms, affecting approximately 66% of patients. The pain of these patients is composed of different conditions, characterized by different etiologies, characteristics and pathological mechanisms. It is estimated that, regardless of stage, up to half of cancer patients feel pain at some point of the disease. Pain in the oncologic patient may manifest as the first symptom of this pathology, during its diagnosis and even during treatment, accompanying the patients to the advanced stages of the disease, where the largest proportion of oncologic patients with pain are found. In view of this, this article aims to address the different management of pain in oncologic patients, with emphasis on interventionist measures and the use of anesthetics for better pain relief.

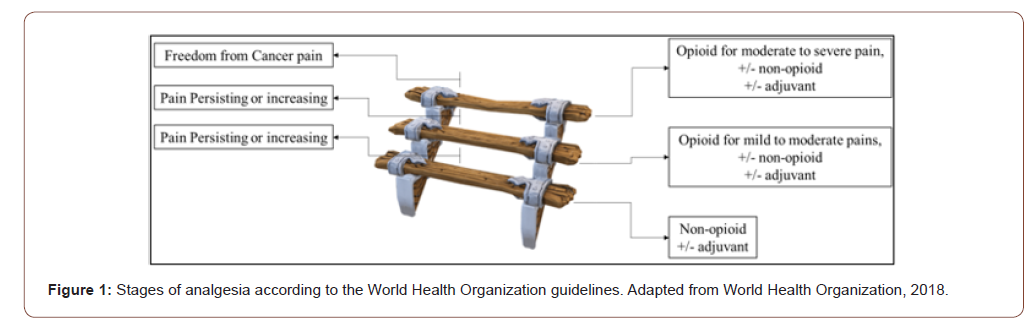

Pain and Oncologic Patient

In view of this, Borda and collaborators, define the general principles of pain management in oncologic patients, with the objective of prolonging survival, optimizing comfort, optimizing function ability and pain relief. In addition, the pain leads to several repercussions, such as insomnia, worry, despair, isolation, depression, among others. Therefore, an individualized treatment for each patient is necessary, besides a multidisciplinary followup, involving psychological and physiotherapeutic follow-up. Thus, the World Health Organization (WHO) has developed a threestep ‘ladder’ to assist pain management in oncologic patients, characterized by the progression of different drug classes, starting with the first step with non-opioids, progressing as necessary to the second step composed of the light opioids, then to the third step, the strong opioids and, if necessary, the use of adjuvant drugs. This approach has proven cheap and effective, and adjuvant therapies should be individualized for each patient if the drugs are not fully effective. On the first step on the ‘ladder’ of WHO pain include acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs), the dose of both drugs is limited by a maximum effect, which when reached there is no benefit in increasing the dose. The second step, composed of mild opioids, is recommended for mild to moderate oncologic pain and includes drugs containing hydrocodone, oxycodone, codeine and tramadol, as well as propoxyfen and dihydrocodeine. Finally, on the third step, WHO recommends its use as first-line therapy for moderate to severe pain, and consists of strong opioids such as: morphine, oxycodone, hydromorphone, fentanyl, levorphanol, methadone (Prommer, 2015) (Figure 1).

Interventionist Actions in Oncologic Pain

Also, according to Prommer [2], there are interventionist modalities, and treatment options include nerve blocks, as well as spinal administration of anesthetics, opioids and other adjuvants. And the adjuvant therapies, which consist of drugs in which their primary indications differ from pain relief, but which have analgesic properties, such as: antidepressants, anticonvulsants, muscle relaxants, corticosteroids, neuroleptics, oral, parenteral and intradermal anesthetics. Thus, the use of anesthetics for the treatment of pain in oncologic patients stands out, and according to Sharma and collaborators [3], the use of only one dose of lidocaine showed improvement in analgesia, Ripamonti [4], reports that the initial recommended dose is 1 to 5 mg/kg infused for 20 to 30 minutes, and should be avoided in patients with coronary artery disease and can be administered subcutaneously. Ketamine, an anesthetic antagonist NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate), has been shown to be effective in the management of oncologic pain and its use generally leads to a reduction in the dosage of opioids in use [5]. There are also interventionist techniques in the management of pain in oncologic patients, with emphasis on anesthetic approaches, such as neuroaxial analgesia, sympathetic blocks of the celiac plexus and upper hypogastric and peripheral nerve block. Neuroaxial analgesia is usually adopted when systemic analgesics are depleted and the addition of local anesthetics or other adjuvants such as clonidine and ketamine to opioids is often considered, and there are reports that pain intensity and quality of life improve with the addition of ropivacaine. The sympathetic blockade of the celiac plexus and superior hypogastric are indicated for patients with abdominal pain with visceral mechanism, this blockade occurs through the injection of local anesthetics. Finally, the peripheral nerve blockade stands out, which consists of applying local anesthetics to block the nociceptive entrance signaling to the central nervous system, the main anesthetics in use are lidocaine, bupivacaine and ropivacaine, Lidocaine is normally considered a local anesthetic of intermediate action (1.5-3 h), while bupivacaine and ropivacaine are local anesthetics of long action (4- 18 h), therefore, for long term therapy with local anesthetics, bupivacaine or ropivacaine are the most adequate [6].

Deer and collaborators [7] also compared the action of Morphine (opioid analgesic) and Ziconotida (non-opioid analgesic) in intratectal application for pain relief in patients with chronic pain associated or not with cancer. Intratectal administration offers benefits over oral analgesics, since they are applied directly at the site of action in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. In the end, it has been proven that both are effective as first line monotherapy for analgesia in cancer patients, giving priority to Ziconotida. Finally, according to Van den Beuken-Van and Cols [8], up to 40% of survivors of cancer have pain and in 5 to 10% the pain is chronic and severe. Therefore, the need for an analgesic approach in oncologic patients, associated with adjuvant therapies, is evident, and the use of anesthetic by different routes of administration has shown beneficial results for pain control and improvement of quality of life in these patients, in addition to reducing the use of opioids, which, if used in the long term, may present side effects, and may lead to greater dependence and overdose [9-29].

Final Remarks

Thus, this work has allowed an overview of the existence of a great diversity of treatments for pain relief in oncologic patients, and interventionist techniques, especially the use of anesthetics, are increasingly being used, either in monotherapy or in adjuvancy, in patients with difficult control, given the promising results in controlling pain symptoms. Faced with this, the knowledge of certain techniques can help health professionals to perform a more precise and resolutive indication, besides guaranteeing a better quality of life and survival to oncologic patients. Finally, there is a lack of research on the use of such techniques in the primary care of these patients, and new studies are needed to evaluate the possible advantages of using them in primary health care.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Caraceni A, Shkodra M (2019) Cancer Pain Assessment and Classification. Cancers 11(4): 510.

- Prommer EE (2015) Pharmacological Management of Cancer related Pain. Cancer Control 22(4):412-25.

- Sharma S, Rajagopal MR, Palat G, Singh C, Haji AG, et al. (2009) A phase II pilot study to evaluate use of intravenous lidocaine for opioid-refractory pain in cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 37(1):85-93.

- Ripamonti C, Bruera E (1996) Pain and symptom management in palliative care. Cancer Control. 3(3):204-213.

- Mercadante S, Arcuri E, Tirelli W, Casuccio A (2000) Analgesic effect of intravenous ketamine in cancer patients on morphine therapy: a randomized, controlled, double-blind, crossover, double-dose study. J Pain Symptom Manage 20(4):246-252.

- Kurita GP, Sjøgren P, Klepstad P, Mercadante S (2019) Interventional Techniques for the Management of Cancer-Related Pain: Clinical and Critical Aspects. Cancers 11(4): 443.

- Deer TR, Pope JE, Hanes MC, McDowell GC (2019) Intrathecal therapy for chronic pain: a review of morphine and ziconotide as firstline options. Pain Med 20(4):784–798.

- Van den Beuken-van MH, Hochstenbach LM, Joosten EA, Tjan-Heijnen VC, Janssen DJ (2016) J Pain Symptom Manag. 51: 1070–1090.

- Becker DE, Reed KL (2012) Local Anesthetics: review of pharmacological considerations. Anesth Prog 59(2): 90–102.

- Boersma FP, Kate-Ananias A, Blaak HB, Touw-Otten F (1993) Effects of epidural sufentanil and a sufentanil/bupivacaine mixture on the quality of life for chronic cancer pain patients. Pain Clin 6: 163–169.

- Bruera E, Ripamonti C, Brenneis C, RNKaren M, John H (1992) A randomized double-blind crossover trial of intravenous lidocaine in the treatment of neuropath - ic cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage 7(3): 138-140.

- Butterwhorth JF, Lahaye L (2018) Clinical use of local anesthetics in anesthesia.

- Caraceni A, Portenoy RK (1999) An international survey of cancer pain characteristics and syndromes. Pain 82(2): 263–274.

- Eisenach JC, DuPen S, Dubois M, Miguel R, Allin D (1995) Epidural clonidine analgesia for intractable cancer pain The Epidural Clonidine Study Group. Pain 61(3): 391–399.

- Guidelines on Pain Management & Palliative Care

- Hayek SM, Hanes MC (2014) Intrathecal therapy for chronic pain: Current trends and future needs. Curr Pain Headache Rep 18(1):388.

- Huang Y, Li X, Zhu T, Lin J, Tao G (2015) Efficacy and Safety of Ropivacaine Addition to Intrathecal Morphine for Pain Management in Intractable Cancer. Mediators Inflamm 439014.

- Interventional Techniques for the Management of Cancer-Related Pain: Clinical and Critical Aspects.

- Intrathecal Therapy for Chronic Pain: A Review of Morphine and Ziconotide as Firstline Options.

- Jadad AR, Browman GP (1995) The WHO analgesic ladder for cancer pain management: stepping up the quality of its evaluation. JAMA 274(23):1870-1873.

- Lauretti GR, Gomes JM, Reis MP, Pereira NL (1999) Low doses of epidural ketamine or neostigmine, but not midazolam, improve morphine analgesia in epidural terminal cancer pain therapy. J Clin Anesth 11(8): 663–668.

- Miguel R (2000) Interventional treatment of cancer pain: the fourth step in the World Health Organization analgesic ladder. Cancer Control 7(2):149-156.

- Pope JE, Deer TR (2015) Intrathecal drug delivery for pain: A clinical guide and future directions. Pain Manag 5(3):175–83.

- SEOM (2017) clinical guideline for treatment of cancer pain.

- Smith HS (2009) Potential analgesic mechanisms of acetaminophen. Pain Physician 12(1):269-280.

- Symptoms (2020) National Cancer Institute.

- Van den Beuken-van EM (2012) Chronic pain in cancer survivors: a growing issue. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 26(4): 385–7.

- Van Dongen RT, Crul BJ, van Egmond J (1999) Intrathecal coadministration of bupivacaine diminishes morphine dose progression during long-term intrathecal infusion in cancer patients. Clin J Pain 15(3): 166–172.

- World Health Organization (1986) Cancer Pain Relief; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland.

-

Douglas Reis Abdalla. Addressing Pain in The Oncologic Patient: The Therapeutic Possibilities in The Pharmacological and Interventionist Field 3(1): 2020. ACRCI.MS.ID.000552.

-

Cancer, Pain, Analgesia, Insomnia, Worry, Despair, Isolation, Depression, Monotherapy, Oncology, Celiac plexus

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.