Case Report

Case Report

Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma Associated with Kasabach Merrit Phenomenon in A Child

Laura Camargo Agón1, Juan Luis Figueroa2 and Oscar E González3*

1Subdirección de Estudios Clínicos y Epidemiología Clínica (SECEC), Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá University Hospital, Colombia

2Department of Pediatrics, Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá University Hospital, Bogotá DC, Colombia

3Department of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá University Hospital, Bogotá DC, Colombia

Oscar E González, Department of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá University Hospital, Bogotá DC, Colombia.

Received Date: December 01, 2021; Published Date: December 15, 2021

Abstract

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma (KHE) is a rare, potentially life-threatening vascular tumor. More than 50% of cases are diagnosed within the first year of life and are often associated with a thrombocytopenic coagulopathy known as Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon (KMP). Approximately 10% of patients die because of this disease, either due to local growth or KMP. Given the rarity of the entity, there have been no prospective studies regarding the treatment of KHE or standardized outcome measures to outline a standard treatment. We describe the case of a female child diagnosed at three months of age with an intraabdominal KHE associated with KMP. She received continuous treatment with vincristine, propranolol, and prednisolone for 10 months until the disappearance of the lesion in images and resolution of the coagulopathy. As a result, she obtained complete remission and now, five years after finishing the treatment, she continues symptom-free.

Keywords: Hemangioendothelioma; Kasabach merritt phenomenon; Consumption coagulopathy; Childhood

Abbreviations: KHE: Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma; KMP: Kasabach merritt phenomenon, MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging

Introduction

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma (KHE) is a rare benign vascular tumor but potentially fatal when associated with Kasabach- Merritt phenomenon (KMP). This phenomenon is characterized by the development of consumption coagulopathy secondary to this vascular malformation; a situation that predisposes to bleeding and other hemorrhagic complications [1]. KHE usually compromises skin and subcutaneous tissue. It typically appears on the lateral neck, axilla, groin, extremities, and trunk. However, numerous case reports have identified KHE in bone, mediastinum, and retroperitoneum [2]. Although they are usually solitary, particularly in the bone, they can present as multifocal lesions. In addition, the direct extension of retroperitoneal and mediastinal lesions in the pancreas, mesentery, pericardium, thymus, and lymph nodes has been reported. There are no significant sex or ethnicity associations, and there are no reports of familial cases underlying genetic mutations [1,2].

There are several treatment modalities such as angiography and embolization, surgical excision, and pharmacologic treatment, with some consensus practice standards towards KHE treatment, however, the low prevalence has limited the standardization of treatment and KMP makes the management problematic, demanding strict adherence and rigorous follow-up [1]. This report describes the case of a three-month-old female patient with an intraabdominal KHE associated with KMP; treatment involved vincristine, propranolol, and prednisolone for 10 months, achieving complete remission.

Case Presentation

A three-month-old female infant was admitted to the emergency room due to four days of irritability, hyporexia, recurrent crying, mild pallor, and petechiae in extremities. She only had a history of gastroesophageal reflux and colic of the infant. Without surgical, traumatic, or positive-allergic history. On admission, she was in an acceptable general state, active and reactive. Due to a tendency to desaturation during sleep supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula at 0.1-liter/minute was initiated. Vitals were within normal limits. At physical examination, she presented mild pallor, petechiae, and ecchymosis on the extremities.

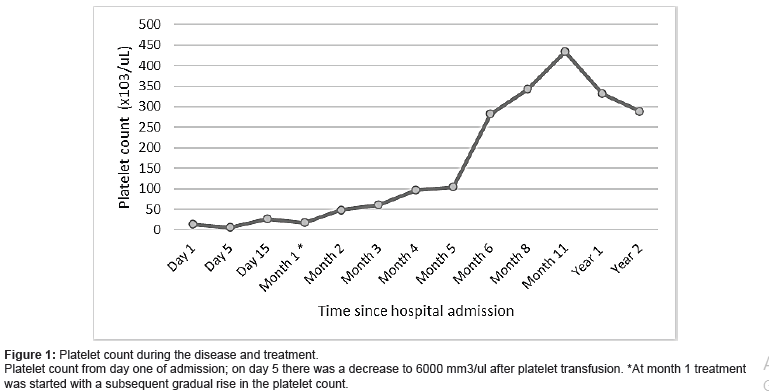

Initial laboratory values showed severe thrombocytopenia (Platelet count 14,700/μL) and anemia (Hb 9,1) (Figure 1).

Infectious, immune, and rheumatologic diseases were ruled out. The initial diagnosis of primary immune thrombocytopenia was considered, and immunoglobulin G was initiated However, at 72 hours it presented an inadequate response with a platelet decrease to 6,000/μL. A bone marrow biopsy was performed after platelet transfusion. The studies in bone marrow revealed megakaryocytic hyperplasia, without blasts.

She continued with severe thrombocytopenia, mild anemia, with normal lactate dehydrogenase, negative direct and fractionated coombs. A wide differential diagnosis of thrombocytopenia in infants was performed [3]. She did not have positive studies for perinatal infections. There was no familiar history of thrombocytopenia. She never presented signs, except for thrombocytopenia and secondary purpuric syndrome, compatible with hemolytic uraemic syndrome or with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. She had platelets of normal size and had no infectious history of albinism or rash that could have indicated a possible hereditary thrombocytopenia type May Hegglin anomaly, or Sebastian’s syndrome. There were no signs of dyserythropoietic or leukemia in the bone marrow and because of her sex, we ruled out thrombocytopenia linked to X. Von Willebrand disease was not suspected since in the variant IIb of this disease the thrombocytopenia usually is very mild. We ruled out storage pool disease because in these diseases the platelet count is normal, and we made a platelet electron microscopy study that didn´t show any abnormalities. Congenital Amegacariocytic Thrombocytopenia or Thrombocytopenia-absent radius syndrome were ruled out because there was no megakaryocytic hypoplasia nor there were alterations in the forearm bones in the x-ray images. We noted low fibrinogen (87.2 mg/dl) and increased D-dimer (> 10000 ng/mL), but there were not any apparent signs on physical examination that suggested vascular abnormalities, and the abdominal ultrasound was reported without any masses nor organomegaly.

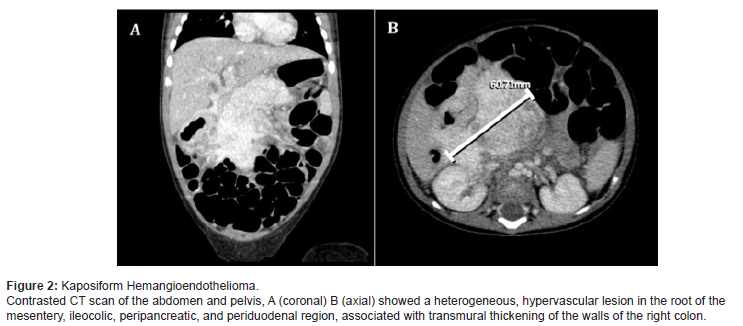

On day fifteen of hospitalization, since she was clinically stable and the platelet count for that time was above 20,000/uL, the study continued ambulatory. After 22 days of discharge, she was readmitted on account of hematochezia with anemia (HB 7, 1g/dl) and thrombocytopenia (17,000/uL). Abdominal CT scan showed transmural thickening of the walls of the right colon, involving the right lateral aspect of the transverse colon, the hepatic angle, and the upper two-thirds of the ascending colon, associated with a lesion in the root of the mesentery, poorly defined, periduodenal, peripancreatic, with involvement of the ileocolic region; it showed heterogeneous enhancement after administration of contrast, compatible with a vascular malformation. Based on manifestations of consumption coagulopathy, KHE and associated Kassabach- Merrit phenomenon were diagnosed (Figure 2).

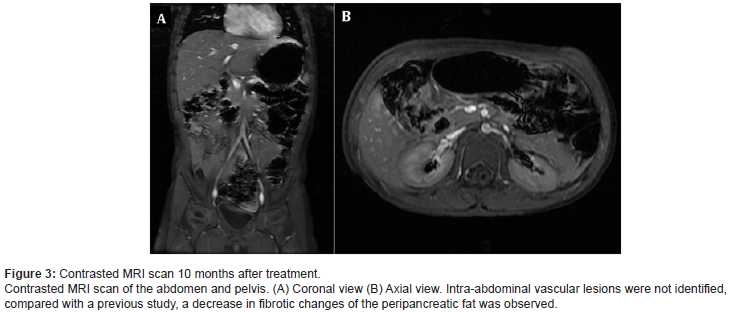

We initiated treatment with an oral prednisolone dose of 3 mg/kg/day divided into two doses per day, propranolol 1.5 mg/ kg/day divided into two doses per day, intravenous vincristine 0.05 mg/kg/weekly, and esomeprazole for gastric protection. The patient showed clinical improvement, without hematochezia or coagulopathy. At week 15 of treatment, platelets were within normal ranges, and fibrinogen and dimer D levels had normalized. Prednisolone was suspended at week 15 of treatment and she continued monotherapy with weekly vincristine. After 10 months of treatment, abdominal MRI showed almost complete remission of the lesion (Figure 3). Given the significant decrease in the size of the vascular malformation, it was decided to stop the treatment. Five years after, she continues without any signs of relapse (Figure 3).

Discussion

KHE is a rare vascular tumor that usually manifests during early childhood, potentially fatal when associated with KMP. This phenomenon is characterized by consumption coagulopathy due to vascular malformations, a situation that predisposes to bleeding and other hemorrhagic complications [2,4]. Even though the presence of KMP in young children is highly suggestive of KHE, reports indicate that KHE can occur without KMP in 29-43% of cases [2]. The management of complicated KHE has been founded on reviews of the available evidence, expert opinion, and clinical experience. However, the approach to treatment must be individualized [5]. Platelet transfusion must be avoided because it worsens the thrombocytopenia and increases the risk of visceral hemorrhage, further promoting tumor growth. It should only be done in cases of active bleeding or where surgical extraction is considered, always just before the surgical intervention, since they are consumed in a few hours [2]. In our patient, the platelet transfusion was made before discovering it was a KHE when it was decided to perform a bone marrow aspiration biopsy to rule out other etiologies as a cause of her thrombocytopenia. Complete surgical excision comes with a high risk of hemodynamic and hematological instability. Therefore, pharmacological therapy is the first line of treatment and surgical excision can be a second-line approach for tumors in which a complete and safe resection can be performed [6,7]. Several treatments have been studied including corticosteroids, ε-aminocaproic acid, pentoxifylline, dipyridamole, and anti-mitotic agents. In certain cases, when pharmacological treatments failed, arterial embolization or radiation therapy had moderate success, but not without long-term risks such as worsening of hematological parameters or development of angiosarcoma when exposed to radiation therapy [8]. Chemotherapy agents used to treat KHE associated with the KMP include intravenous vincristine (0.05mg/ kg/weekly dose is the recommended dose) and oral corticosteroids (prednisolone 2mg/kg/day). We were able to corroborate with our patient, that the combination of prednisolone with propranolol both days; and weekly vincristine is a very effective and safe treatment alternative. Patients with KMP should be treated aggressively with a combined regimen, and monotherapy is not recommended [9,10].

The goal is to wean the corticosteroid as soon as possible after 3 to 4 weeks of therapy if there has been a good clinical response and stabilization of the patient’s hematologic status. The intended length of vincristine therapy is typically 24 weeks [1] but should be individualized to each patient, following tumor response, and avoiding related toxicity. In the described case, 10 months of treatment were enough to achieve a complete and sustained long-term response. Successful treatment is also possible with a combination of vincristine at the dose noted plus aspirin: 10 mg/ kg/day and ticlopidine: 10mg/kg/day [11] or Interferon-alpha. Nonetheless, the use of interferon-alpha in children is limited by cost, and due to the subcutaneous administration route [8].

Sirolimus is a promising agent for KHE and some prospective studies have shown it is safe and efficient in this pathology. However, the evidence of sirolimus in children against KHE is still limited. It’s usually used in cases refractory to the combination of vincristine and steroids, given orally with close pharmacokinetic monitoring [12,13]. Residual tumor or fibrosis is common, especially in more aggressive lesions, and is not a reason to continue therapy if highrisk symptoms have resolved and the tumor is stable on serial imaging.

Despite the rare occurrence of KHE that makes it difficult to identify a standard therapy, steroids plus vincristine seem to be a good choice for first-line treatment, highly effective, economical, and with a relatively low side-effect rate. Further reports are necessary to strengthen our knowledge of these lesions.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Drolet BA, Trenor CC, Brandão LR, Chiu YE, Chun RH, et al. (2013) Consensus-derived practice standards plan for complicated Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma. J Pediatr 163(1): 285-291.

- Croteau SE, Liang MG, Kozakewich HP, Alomari AI, Fishman SJ, et al. (2013) Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: atypical features and risks of Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon in 107 referrals. J Pediatr 162(1): 142-147.

- Kaplan RN, Bussel JB (2004) Differential diagnosis and management of thrombocytopenia in childhood. Pediatr Clin North Am 51(4): 1109-1140.

- Kelly M (2010) Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon. Pediatr Clin North Am 57(5): 1085-1089.

- Chiu YE, Drolet BA, Blei F, Carcao M, Fangusaro J, et al. (2012) Variable response to propranolol treatment of kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, tufted angioma, and Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon. Pediatr Blood Cancer 59(5): 934-938.

- Hermans DJJ, Van Beynum IM, Van der Vijver RJ, Kool LJS, De Blaauw I, et al. (2011) Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma with Kasabach-Merritt syndrome: a new indication for propranolol treatment. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 33(4): e171-e173.

- Abass K, Saad H, Kherala M, Abd Elsayed AA (2008) Successful treatment of kasabach-merritt syndrome with vincristine and surgery: a case report and review of the literature. Cases J 1:9.

- Harper L, Michel JL, Enjolras O, Raynaud Mounet N, Rivière JP, et al. (2006) Successful management of a retroperitoneal kaposiform hemangioendothelioma with Kasabach Merritt phenomenon using alpha-interferon. Eur J Pediatr Surg 16(5): 369-372.

- Ryan C, Price V, John P, Mahant S, Baruchel S, et al. (2010) Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon: a single centre experience. Eur J Haematol 84(2): 97-104.

- Rodriguez V, Lee A, Witman PM, Anderson PA (2009) Kasabach-merritt phenomenon: case series and retrospective review of the mayo clinic experience. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 31(7): 522-526.

- Fernandez Pineda I, Lopez Gutierrez JC, Chocarro G, Bernabeu Wittel J, Ramirez Villar GL (2013) Long-term outcome of vincristine-aspirin-ticlopidine (VAT) therapy for vascular tumors associated with Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon. Pediatr Blood Cancer 60(9): 1478-181.

- Sirolimus (rapamycin) in patients with kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: case report.

- Wang H, Guo X, Duan Y, Zheng B, Gao Y (2018) Sirolimus as initial therapy for kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma. Pediatr Dermatol 35(5): 635-638.

-

Laura Camargo Agón, Juan Luis Figueroa, Oscar E González. Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma Associated with Kasabach Merrit Phenomenon in A Child. Adv Can Res & Clinical Imag. 3(3): 2021. ACRCI.MS.ID.000563.

-

Hemangioendothelioma, Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon, consumption coagulopathy, childhood

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.