Case Report

Case Report

Myofascial TMD, Multifactorial Ethiology with Multidisciplinary Approach- A Case Report

Evangelista De Leon Reimy1, Cheung Andy2, Donavon Khosrow Aroni1 and Marefat Mahpareh3*

1Department of Diagnostic sciences, Craniofacial Pain and Headache Division, School of Dental Medicine, Tufts University, USA

2School of Dental Medicine, Tufts University, USA

3Department of Periodontology, School of Dental Medicine, Tufts University, USA

Marefat Mahpareh, Department of Periodontology, School of Dental Medicine, Tufts University, USA

Received Date: July 20, 2020; Published Date:August 31, 2020

Abstract

Temporomandibular disorder (TMD) is a broad term refers to pathophysiology related to the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), masticatory muscles and associated head and neck structures. It may present wide spectrum oral manifestations, such as abnormal tooth wear, soft and hard tissue injuries and facial pain [1]. It has been a great challenge to clinically diagnose and to effectively manage this condition because of incomplete understanding and multifactorial etiology. A comprehensive examination following Diagnostic Criteria (DC/TMD) helps the clinicians with more proper clinical assessment of TMD patients [2]. This indicates a multidisciplinary approach including dental treatment, oral orthotic device(s), pharmacotherapy, physical medicine and proper referrals to other health care providers including pain specialists.

Introduction

Temporomandibular disorder (TMD) refers to pathophysiology changes related to the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), masticatory muscles and associated head and neck structures [1]. Common symptoms of TMD include jaw pain, jaw noises (clicking and crepitus), functional movements limitations, limited range of motion (ROM), earache, headache and facial pain [1]. The etiology of TMD is multifactorial including biological, environmental, social and psychological factors [1]. Myofascial pain is the most common orofacial pain condition and the second most common musculoskeletal condition resulting in pain and disability after chronic lower back pain [3]. TMD prevalence is 5%-12% among US adults [3]. The annual incidence is nearly 4%. It is most common in the 20-to 40-year age group and has double the occurrence in women as compared to men [3]. The Annual TMD health care costs are $4 billion US dollars highlighting treatment needs [3]. This makes it extremely important for health care providers to complete a comprehensive evaluation. This should include a history of present illness, review of systems, medical history, psychosocial history, sleep history, intra and extra-oral exams including muscle palpation and other appropriate diagnostic exams, screening questionnaire and diagnostic tools [1].

Case Report

A 46-year-old Asian male was seen at Tufts University School of Dental Medicine (TUSDM) undergraduate clinic, with chief complaints of jaw and neck pain associated with headaches for the past 6 years. No trauma to the head and neck region has been reported. He wakes up with average moderate [Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) 5-7/10] [4] daily headaches. Theses headaches are continuous with throbbing, dull and tight quality. Headaches are bilateral and starting on the preauricular areas radiating to the temporal areas, neck and upper back region. These headaches are not causing nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia or any visual disturbances. The patient is aware of being a heavy grinder and believes that his jaw pain and headache are associated with this parafunctional jaw activity. He has also reported a persistent, continuous, moderate, throbbing, dull and tight bilateral jaw and neck pain. It is also originating from the preauricular area and seems to radiate to the lower-left molar areas. The pain is worst in the morning with average moderate (5/10 NRS) intensity and aggravated by chewing and prolong talking and is partially alleviated by pain medication Motrin 1000 mg daily 3-4 days a week. The patient also had other previous treatments including acupuncture and massage with temporary limited partial benefit.

The review of systems and medical history was completed with negative findings. No significant family medical history reported. The medication list was reviewed and besides Motrin 1000 mg (OTC) once a day he was taking recreational Cannabis (Sativa) for pain management. The patient also reported using cannabis helps his sleep issues as difficulty falling asleep (due to the pain). However, he denied difficulties to maintain sleep. He denied any other sleep related symptoms but grinding. The patient has had different oral appliances in the past to address his sleep-related bruxism, but it seems to aggravate his headaches.

A brief psychosocial history obtained, and the patient was alert, well oriented, and has normal speech with full range of affect during the visit. He is single and has no children, works full time and denied alcohol intake. The patient self-diagnosed himself with depression and anxiety. He described that most of his anxiety and depressions are due to his jaw pain and headache. He described that he is frustrated due to the lack of explanation for his current symptoms but denied any suicidal ideation (S/I). However, he reported that those thoughts have passed through his mind “when you are in so much pain with no hope or answers you can feel like this”. During the initial appointment, he seemed more optimistic “I can see some hope and I feel I’m in the right direction now”. The patient denied heart rate raising or palpitations, fears or phobias, and panic attacks associated with his self-reporting anxiety. The patient was not under the care of any psychologist/therapist. However, consultation with a psychologist was recommended. During the initial appointment, his mood was fairly stable with a cooperative attitude, had direct eye contact, appropriate expressions, some difficulties to recall specifics details. Screening questioners were obtained (PHQ-9=16 and GAD-7=12) [4] based on which moderate anxiety and depression are suspected. The Patient scored positive for item #9 of the PHQ-9 for S/I. Consultation with Primary Care Physician (PCP) and psychologist was scheduled immediately.

General examination indicated the patient is fit and wellgroomed. BMI is consistent for Healthy Weight (18.5 - 24.9) [5]. No physical alterations, abnormalities or pathologies were identified during general visual examination. Cranial nerve screening is grossly intact, cranial nerve V and VII are essentially normal; sensory deficit and facial weakness could not be identified during examination. Visualization and palpation of the facial soft tissue including lips did not indicate any bleeding, sores, dryness, swelling, edema or masses. No asymmetry of structures or function surface abnormalities. The head posture was maintained slightly forward in relation to the coronal plane and the shoulder posture was slightly rounded in relation to the sagittal plane. Intraoral examination was completed. Teeth observed with generalized abrasion consistent with his parafunctional habit of sleep-related bruxism. Missing teeth #19 and 30. Dental and skeletal midline deviated to the right. Preexisting lower resin-based partial denture was rocking and the patient labeled it as uncomfortable.

Mild generalized gum inflammation was observed consistent with gingivitis characteristics, slight localized gingival inflammation, rolled shape, enlarged size, and smooth texture [6]. No other soft tissue abnormalities or pathologies observed. The oral mucous membranes appear normal, with no soft tissue swelling, lesions, or areas of discoloration noted. The floor of the mouth was soft and non-tender. There was free-flowing clear saliva that could be expressed from the parotid ducts and submandibular ducts bilaterally. Canine Classification I. Normal movements with no visible pathologies of the soft palate, tongue and uvula. The patient is consistent with Mallampati class III. A horizontal class III impacted third molar was observed on the lower left jaw. TMJ range of motion (ROM) was recorded as 9 mm right lateral, 10 mm left lateral, 8 mm protrusive, maximal opening of 45 mm and minimal deflection to the right upon maximum opening. Extraoral examination and muscle palpation were completed following DC/TMD guideline [2]. Moderate pain was elicited during initial examination upon palpation of masseter, temporal tendon and temporalis bilaterally. The patient confirmed familiar pain and headache intensity increased after palpation. Mild to moderate pain was also elicited by palpation of Sternocleidomastoid (SCM), posterior neck muscles and trapezius bilaterally. The patient confirmed the pain perceived on the trapezius as familiar pain. Functional test for lateral pterygoid reported moderate pain after pressure was relieved. Mild pain upon palpation of the right lateral pole of the TMJ was elicited. However, no clicking or crepitus was observed upon auscultation during the examination.

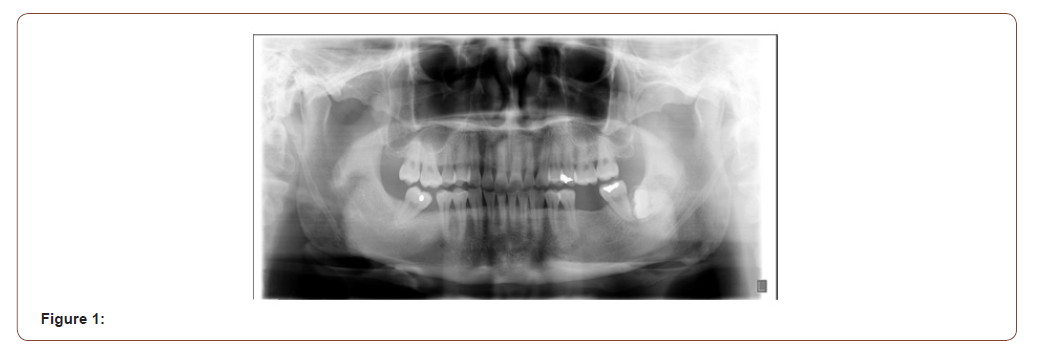

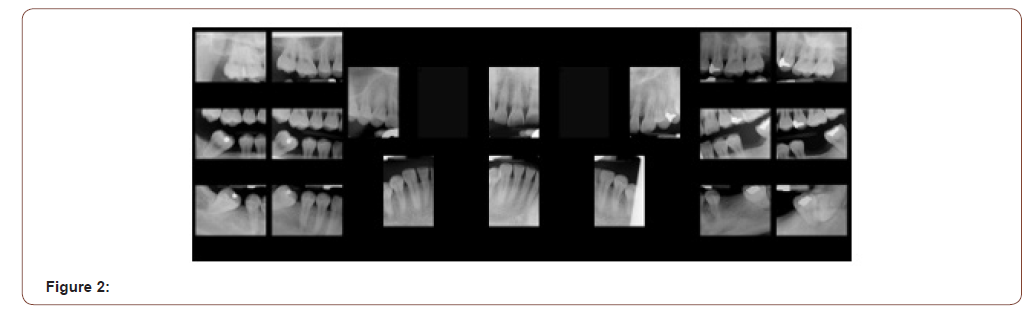

Panoramic X-ray revealed the mandibular condyles to be fairly normal in size, shape and are reasonably symmetrical. There was a good radiographic cortical margin on both mandibular condyles and no evidence of any gross degenerative changes. Bilateral ossification of the stylohyoid ligament noted. No other obvious osseous pathology or obvious detectable odontogenic lesions were noted. It indicates impacted tooth number 17. An Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery (OMFS) consult was obtained and Conebeam Computerized Tomography (CBCT) was recommended for an in-depth evaluation. However, the patient refused the CBCT (Figures 1 & 2). The mentioned clinical features of the present physical discomfort; including subjective symptomatic reports, history of present discomfort, clinical signs, intraoral and extraoral examinations in conjunction with the imaging findings, collectively can be in part indicating musculoskeletal dysfunction usually accompanied by pain. This can be a contributory factor to ongoing clinical features and its manifestation. The presence of pain elements is also suggestive of myofascial pain as a contributing factor to the ongoing symptoms. It’s also possible that the headaches are triggered and/or intensified by muscle tightness in the jaw and neck region. The comorbid psychosocial factors seem to have exacerbated the current symptoms.

The following planned interventions considered based on clinical findings. Referral for biobehavioral evaluation, initiation of oral orthotic device therapy, pharmacotherapy (muscle relaxant), reassessing the current unstable removable partial denture (RPD) and referral for complementary medicine (acupuncture, physical therapy, …). During the initial appointment, an upper stabilization oral orthotic was fitted. It was recommended to use it during sleep and return for follow up in 6 weeks. After reviewing allergies and medical history and discussing possible side effects, prescription for cyclobezaprine 10 mg once a day was provided. The patient returned for follow-up visit in 6 weeks and reported discontinued the use of cannabis. He reported significant improvement of his jaw pain and sleep “I don’t need cannabis anymore”. His headaches have improved “they are gone”. The patient seeing a psychologist twice a month. He seems optimistic about life and looking forward to the future. The second round of screening questioner (PHQ-9=8 and GAD-7=7) [3] obtained which indicated reductions of the patient’s mental comorbidities suggesting mild anxiety and depression. The Patient scored negative for item #9 (S/I) of the PHQ-9. He described the upper appliance being useful and very comfortable and there is less jaw muscle tension upon awakening. He was referred also to TUSDM prosthodontic department for fabrication of a new RPD and he reported it fits better and feels comfortable. The patient reported that physical therapy has reduced the tension on his neck and helped him to go back to exercising daily.

Discussion

Myofascial pain disorder is the most common of all TMDs, and it is usually multifactorial. These factors include biological, behavioral, social, emotional and cognitive factors either acting alone or in combination with each other. Chronic pain and illness frequently create sleep disturbances, depression, and anxiety [7]. Comorbidities associated with depression and anxiety are critical and common with chronic pain. In the diagnosis of chronic illness, two measuring tools are used to help focus on treating the underlying the issues. This categorizes the patients in Axis I (biological) and Axis II (psychosocial) [8]. The most common symptom reported by patients with TMD is unilateral face pain that may radiate to the ear, temporal, periorbital regions to the angle to the mandible and posterior neck. The pain is usually described as a dull, constant ache that persists through the day with the pain worst in the mornings, including bouts of severe, sharp pain usually triggered by the movement of the mandible [9]. A neurological examination is also important to observe and identify for any neurosensory or motor deficits of the cranial nerves. Combined with screening surveys concerning depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances using PHQ- 9, GAD7, Epworth sleepiness scale and/or stop-bang questionnaire helps to assist in screening for commodities of chronic illness. Specific type of imaging is another important diagnostic tool to assist in differential diagnosis utilizing pantographs as an initial image to screen for abnormalities. Applying the initial screening question for our patient, we suspected moderate-severe depression and anxiety and positive response to question #9 on the PHQ-9 claiming suicide ideation. On the sleep disturbance questionnaire, no suspicion of sleep loss or obstructive sleep apnea was observed, only an indication of sleep-related bruxism presented on the occlusal facet of the molars and anterior teeth. From the initial radiograph, abnormalities of soft tissue concerning the stylohyoid ligament exhibit elongation and ossification without symptoms to clinically diagnosis Eagle syndrome which present with pain or discomfort, limited mobility of the head, and neck and pain in the oropharyngeal region involving the network of vascular and neural structures is also common [10]. Ultimately, advanced imaging with computed tomography (CT) for hard tissue, and in some other TMD cases, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for soft tissue are better tools to aid in diagnosing.

Managing and treating TMD-related symptoms may need multidisciplinary approach consist of a combination of home self-care, counseling, pharmacotherapy, and other noninvasive reversible treatment including a custom oral appliance to manage musculoskeletal pain, spasms, and preventing occlusal wear. Oral orthotic device(s) can be used as the first line of treatment when the patient presents with occlusal wear due to sleep-related bruxism. This device(s) is designed to reposition or stabilize the TMJ and associated soft and hard tissues by altering joint mechanics and mobility, relieving masticatory muscles tension to reduce muscle pain induced bruxism. Faulty fabricated oral appliances my trigger, provoke or aggravate parafunctional activity and may exacerbate the pain and dysfunction. Properly designed custom fabricated oral orthotics have shown to reduce pain and dysfunction of the TMJ in 70-90% of patients [7]. The importance of a comprehensive examination, health history and psychosocial review is important for differential diagnosis and designing treatments implementing oral appliances, pharmacologic, physical and psychiatric therapy.

Conclusion

Myofascial pain disorder has been described as pain originating from a single trigger point radiating to adjacent musculoskeletal structures. It can trigger, provoke or aggravate pain and limitation in jaw movement, head, ear and neck pain, and negative psychosocial behavior contributing to depression and anxiety. As described in our case report, it is important to perform a comprehensive medical, physical and psychosocial examination to determine a proper differential diagnosis. When myofascial pain disorder is indicated with comorbidities affecting physical and psychosocial modalities, referral to appropriate medical professional colleagues should be considered for further assessment and prompt treatment. Myofascial pain disorder has responded well with combination of different approaches including oral orthotic, pharmacological, physical and psychiatric therapy.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflicts of Interest

No Conflicts of Interest.

References

- De Leeuw R, Klasser GD (2018) Orofacial Pain: Guidelines for Assessment, Diagnosis, and Management. The American Academy of Orofacial Pain, 6th (Edn.), Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc, USA.

- Eric Schiffman, Richard Ohrbach, Edmond Truelove, John Look, Gary Anderson, et al. (2014) Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 28(1): 6-27.

- Carolina Beraldo Meloto, Gary D Slade, Ryan N Lichtenwalter, Eric Bair, Nuvan Rathnayaka, et al. (2019) Clinical predictors of persistent temporomandibular disorder in people with first-onset temporomandibular disorder. A prospective case-control study. J Am Dent Assoc 150(7): 572-581.

- (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Dsm-5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, USA.

- Nuttall Frank Q (2015) Body Mass Index: Obesity, BMI, and Health: A Critical Review. Nutr Today 50(3): 117-128.

- Leonardo Trombelli, Roberto Farina, Cléverson O Silva, Dimitris N Tatakis (2018) Plaque-induced gingivitis: Case definition and diagnostic considerations. J Clin Periodontol Suppl 20: S44-S67.

- Jie Lei, Mu Qing Liu, Adrian U Jin Yap, Kai Yuan Fu (2015) Sleep disturbance and psychologic distress: prevalence and risk indicators for temporomandibular disorders in a Chinese population. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 29(1): 24-30.

- Reiter Shoshana, Alona Emodi-Perlman, Carole Goldsmith, Pessia Friedman-Rubin, Ephraim Winocur (2015) Comorbidity Between Depression and Anxiety in Patients with Temporomandibular Disorders According to the research Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 29(2): 135-143.

- Scrivani, Steven J, et al. (2008) Temporomandibular disorders. The New England journal of medicine 359(25): 2693-705.

- A W Barrett, M J Griffiths, C Scully (1993) Osteoarthrosis, the temporomandibular joint, and Eagle's syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 75(3): 273-275.

-

Marefat Mahpareh. Myofascial TMD, Multifactorial Ethiology with Multidisciplinary Approach- A Case Report. Arch Clin Case Stud. 2(5): 2020. ACCS.MS.ID.000546.

-

Temporomandibular disorder, Injuries, Jaw pain, Dryness, Swelling, Sternocleidomastoid, Depression, Muscle pain.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.