Research Article

Research Article

Epidemiological Study of the Eagle’s Syndrome Through Panoramic Radiographs of Adults from A Brazilian Population

Anny Isabelly dos Santos Souza1, João César Guimarães Henriques2, Fabio Franceschini Mitri3*

1Student from School of Dentistry, Federal University of Uberlandia, Uberlandia/MG, Brazil

2Professor Doctor at the Department of Stomatological Diagnosis, School of Dentistry, Federal University of Uberlandia, Uberlandia/MG, Brazil

3Professor Doctor at the Department of Human Anatomy, Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Federal University of Uberlandia, Uberlandia/MG, Brazil

Doctor Fabio Franceschini Mitri, Department of Human Anatomy, Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Federal University of Uberlandia, Uberlandia/MG, Brazil

Received Date: November 07, 2022; Published Date: November 29, 2022

Abstract

Eagle’s syndrome is characterized by elongation of the styloid process which is resulted of the calcification of styloid ligament, and it is usually asymptomatic, however, it is of a notorious clinical relevance in the area of head and neck. The purpose of this research is study is to draw up the epidemiologic profile of the Eagle’s syndrome, regarding to age group, sex, and side, in 463 panoramic radiographies of Brazilian adult patients from a School of Dentistry. Our results have revealed 83 cases (17.9%), divided into 51 men and 32 women (61.4% e 31.4%), 44 bilateral and 39 unilateral (53% and 47%), all distributed into 29 in right side and 10 in left side (35% and 12%). Most cases have been observed in the second, third, fifth and sixth age groups. The statistical analysis has been revealed significant difference to the men (P=0.0006) and in the right side (P=0.0001), when p<0.05. We have been concluded that the Eagle Syndrome is prevalent in men young adults, with a predominant bilateral occurrence, and when it is unilateral, the right side was significantly affected. The knowledge of the epidemiologic profile is essential in a clinical context, regarding an updating of clinical protocol and the proper management since it is a generally a well-known asymptomatic condition in the world literature.

Keywords: Eagle’s Syndrome; Panoramic Radiograph; Epidemiology

Introduction

The Eagle’s syndrome has been first launched in 1937 by otolaryngologist Watt Wems Eagle [1]; it occurs through the ossification of the stylohyoid ligament resulting in the elongation of the styloid process. Its aetiology is usually idiopathic or maybe due to a surgical injury [2]. The styloid process is a thin bony cylindrical projection with up to 30 mm long, and it is lying on the tympanic portion of temporal bone at the base of skull, anteromedially to the stylomastoid foramen [3,4].

The worldwide incidence of this syndrome ranges from 4% up to 30% [3,5,6], and is reported rare in children. The majority of cases is asymptomatic, nonetheless, when is symptomatic, there are some discomfort or cervical pain during rotation of the head or yawning, odynophagia, foreign body sensation in neck, auricular symptomatology like tinnitus and neuralgic pains [7-10]. The diagnosis runs from the medical history associated to intra-oral clinical examinations, which are conducted by palpation on tonsillar region. Nonetheless, imaging exams like panoramic radiograph and Citation: Anny Isabelly dos Santos Souza, João César Guimarães Henriques, Fabio Franceschini Mitri*. Epidemiological Study of the Eagle’s Syndrome Through Panoramic Radiographs of Adults from A Brazilian Population. Arch Clin Case Stud. 3(2): 2022. ACCS. MS.ID.000560. DOI: 10.33552/ACCS.2022.03.000560. Page 2 of 6 CT scan are essential to view the elongation of the styloid process [11]. It is very clear that throughout the decades, the clinicians and researchers have been demonstrated great clinical interest about this condition, otherwise, the epidemiological studies are much few in latest years, in contrast to clinical case reports. The importance of this kind of investigation is to provide a tool so that the clinicians can understand the anatomy of hyoid apparatus, and also to know the clinical features and symptoms, which could be overlooked for the simple fact of not understanding the Eagle syndrome. So, the purpose of this research is to comprehend the prevalence of the Eagle syndrome in patients from Brazil, verifying its distribution according to age, sex, and the affected side, building an epidemiologic profile in adults.

Material and Methods

Introduction

This research comprises a retrospective study to determine an epidemiological profile about the Eagle syndrome. It was performed from clinical observation of 463 panoramic radiographs of the face of the adults from Department of Stomatology of Federal University of Uberlandia, Brazil. The research has been approved by Ethics Commit in Research with Human Beings, under protocol 4.047.067. The analysis on the imaging exams have been realized and the measurement of the bilateral styloid process was performed by using of a digital caliper (Mitutoyo MTI Corporation, Crystal Lake, Illinois USA), so the length has been expressed in millimetres (mm). The styloid process has been considered elongated when exceeding 30 mm [4,12,13], meaning diagnosis of Eagle syndrome. The variables like sex, age, and side were correlated. The numeric and percentage calculation have been performed with the Microsoft Excel 2021 (2021 Microsoft Corporation) [14] the chi-square test with maximal significance level of 5% (p<0,05) [15] was applied to investigate a possible association between Eagle syndrome with sex and side. This statistical analysis was performed on SSPS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA), version 10.0.

Result

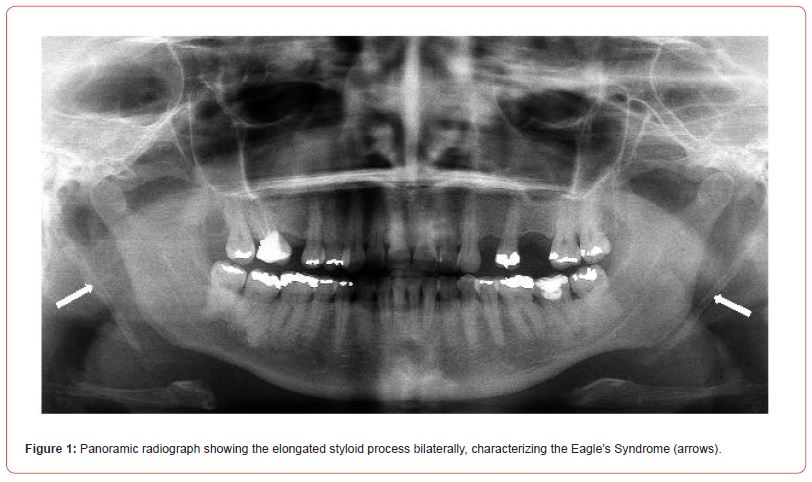

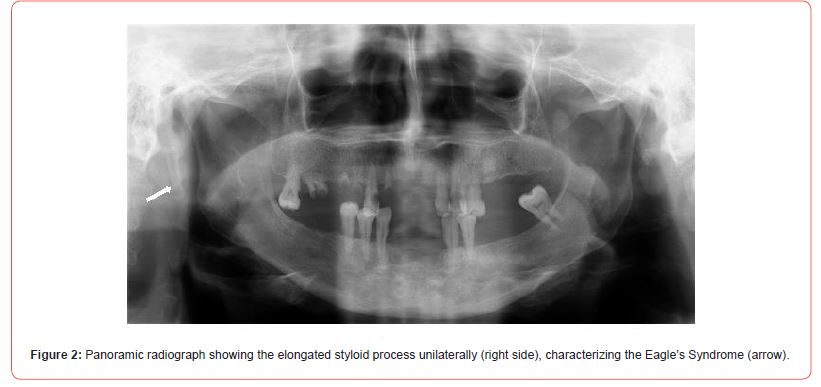

The styloid process was analysed through the observation of the 463 panoramic radiographs and measured bilaterally, including randomly 206 men and 257 women. When lengths are bigger than 30 mm, these were characterized by Eagle syndrome. These points were analysed regarding age, sex, and side (Figures 1 & 2).

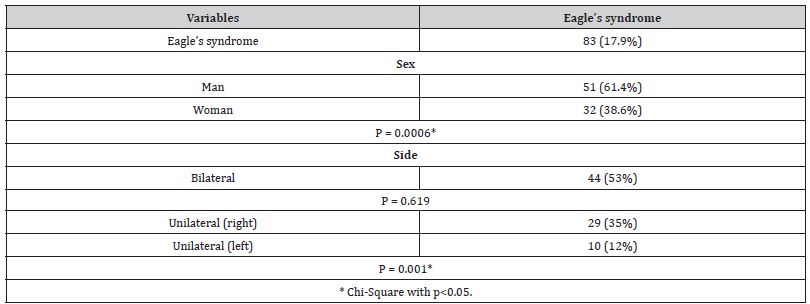

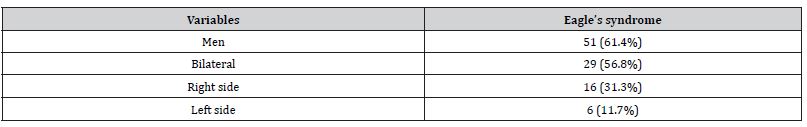

Table 1 shows a general view of the results. There were 83 cases of Eagle syndrome, which represent 17.9% in total, of which were 51 males and 32 females, 61.4% and 38.6% respectively, from the total of 463 panoramic radiographs of the face. Moreover, there were 44 bilateral cases (Figure 1) and 39 unilateral (Figure 2), being 53% and 47%, they were distributed in 29 in right side and 10 in left side, which they represented 35% and 12%, respectively. Chi-square test did not reveal any correlation between bilateral and the unilateral ones (P = 0.619); nonetheless, it has revealed a statistical significance in two variables, of which the male sex (P = 0.0006) and the right side (P = 0.0001). Regarding all cases of Eagle syndrome diagnosed by the imaging exam, this research has revealed 29 bilateral cases (56.8%) in males, distributed into 16 (31.3%) to the right side and 6 (11.7%) to the left side. Additionally, 15 bilateral cases (46.8%) in females with 13 (40.6%) in the right side and 4 (12.5%) in the left side (Tables 1 & 2).

Table 1: Prevalence of Eagle’s syndrome regarding gender and side, in 463 radiographies.

Table 2: Prevalence in men with Eagle’s syndrome, in 463 radiographies.

The Eagle cases here identified have also been related divided into age groups. There was 1 case into the age group of 18 and 19 years old (1.2%), 23 cases into the second decade of life (27.7%), 10 into the third (12%), 7 into the fourth (8.5%), 17 into the fifth and sixth (20.5%), 4 into the seventh (4.8%), 3 into the eighth (3.6%), and 1 case into the nineth decade of life (1.2%). Considering all of 463 radiographs, these data represented the following percentages of 0.2%, 5%, 2.1%, 1.5%, 3.7%, 0.9%, 0.6% e 0.2% respectively to those ones age groups (Tables 3 & 4).

Table 3: Prevalence in women with Eagle’s syndrome, in 463 radiographies.

Table 4: Prevalence of the Eagle’s syndrome regarding age group, in 463 radiographies.

Discussion

The quantitative analysis over the styloid process length can be surely performed in both dry skulls and imaging exams [6,16]. Panoramic radiography is easily interpreted by direct visualization and useful in Eagle syndrome investigation [17]. Like this in current research, the Eagle syndrome has been diagnosed by clinical observation in panoramic radiographies according to the classification of styloid process length reached by Sokler and Sandev in 2001, who have been reported a short styloid process when the length is up to 21mm, normal length between 21 and 30mm, and the elongated styloid process higher than 30mm. Painful symptomatology could be strongly associated to the styloid process higher than 40mm [18]; this condition has not been found in our study. So, based on this previous sentence, we could think here that all cases studied in our current research would supposedly be asymptomatic.

The styloid process is between the internal and external carotid arteries, posteriorly to the tonsillar fosse, and laterally to pharynx and the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerve. Based on it when the symptoms or discomforts are presents, they could be associated to these anatomical structures. Over decades, the symptomatology of the Eagle syndrome has been reported in a variation rate of 4 up to 28% of diagnosed cases [2,18]. So, there is a need for new research to clarify the real points who could trigger its range of symptoms and pointing the clinical variety of this syndrome.

Our results have revealed an interesting prevalence of the Eagle syndrome in a Brazilian adult population, being 83 cases into a total of 463 individuals, representing 17,9% of prevalence. Regarding this, the condition does not seem to be rare as pointed out by other work [10]. Some studies also have been showed a prevalence of 28% [18] or 30% [5]. We could clearly hypothesise here that the rare condition may be associated with the studied population.

The current research also has revealed a higher prevalence statistically significant of the Eagle syndrome in men in agreement to other statistical study [15] and other ones with percentage calculation [19,20]. In contrast, studies of percentage calculation also revealed a higher number of diagnosed women [21-23] or with a similar distribution into both sexes [24]. We could say here that the sex is not a dominant variable to this syndrome or that it could be associated to a target population. The most of research drew up an epidemiologic profile by the percentage calculation way. A higher statistical prevalence of this syndrome in men also has been revealed in our research, according to other ones over statistical analysis [15], and percentage calculation analysis [19,20].

Furthermore, our research also has showed a common occurrence of the bilateral elongation of styloid process compared to the unilateral ones, according to other studies [23,24], with the statistically prevalence on the right side. We could think in a hypothesis to be investigated that whether the physiology of a commonly asymmetric muscle tonus would be associated with the higher prevalence of right unilateral in the right-handed people. This idea could explain the higher prevalence in men, who generally have a greater muscle strength than women.

Considering age groups, our research also has revealed a higher number of cases in the second decade of life, followed by similarly fifth and sixth life decades, third and finally the fourth. The first and nineth decades were less affected by the age group, followed by the seventh and eighth. These data agree accordingly with other studies which have pointed the majority of the diagnosed cases into the age of forty [22]. Further investigations also should be carried out on children or the underage population to draw an epidemiologic profile of the Eagle syndrome. Therefore, the prevalence on each age group here can be relative, which means the elongation of styloid process has not occurred exactly in this age, but yes that it could have been radiographically detected in that time, since that probably a great number of cases are asymptomatic. This current research brings to the scientific field the epidemiologic profile of Eagle’s syndrome in a part of Brazilian population, since this type of study is scarce in the world literature, and the case report are the majority instead. Here is a tool to provide clinicians an important information over the syndrome’s occurrence in a population. When the symptoms are present, they could be easily confused with other conditions leading to a diagnostic error. This hypothesis could be supported by a well-known expression by clinicians as “radiographic finding”. It can be surmised that many of these cases could have been by mistake of diagnosis on wrong radiographic interpretation or a misunderstanding about signals and symptoms coming from an inappropriate anamnesis. This syndrome could resemble other conditions [16] so some symptoms described from patient could be confounded with regularly situations of day by day, such as strange body on throat or auricular pain by inflammation, a cold condition, emotional instability, or even in situation of a low water intake. And even discomfort on cervical region during head rotation could be misdiagnosed as resulted by a regional muscle contracture or strain. These features could be due to an overlooking of the clinical condition, failure in anamnesis or physical examinations and the non-requested proper exams. Like this, a condition which has been overlooked could evolve to severe sequels in the patient.

The elected term “radiographic finding” should be misunderstood by untrained clinicians, who could apply it to any supposedly idiopathic condition, so overlooking any condition accomplished of signals and symptoms with important clinical relevance. What we would like to mean here is that the use of the reported term is not wrong, therefore, its general idealization could lead to a set of clinical errors and even iatrogenic. Additionally, it is worth mentioning that the low incidence really makes the Eagle’s syndrome as a diagnosis challenge, since this condition is based on clinical suspicion, which is especially increased by the symptomatic ones, and decreased or null by asymptomatic ones, being usually confirmed by imaging exams [25].

An interesting, rare case of choking as resulted by Eagle’s syndrome has been reported by Gupta and cols, in 2017, in which the autopsy revealed food particles traced into bronchioles and the parenchyma of the right lung of the patient arising from the elongation of styloid process bilaterally by ossification of styloid ligament, which has been caused impaction of the food into the upper respiratory tract. This report strongly supports the hypothesis over the importance of an accurate clinical investigation over this syndrome by clinicians like a new clinical approach protocol, as well as the usual clinical following specially to the asymptomatic ones.

This syndrome’s prevalence has been reported earlier by Eagle, in 1958, in 4% of population, however, it seems has increased over the decades [3,19]. This can be due to the increasing interest from research in the subject [6], and to the knowledge widely disseminated in the world literature through clinical cases report, which raises awareness of clinicians to all range of symptomatology (Badhey et al., 2017). The increasing advance of technology associated to the availability of x-rays apparatus both in private and public health services, and the increase of requires of imaging exams also contribute to the correct diagnosis. Like this, there is a demand for new epidemiologic investigations, which could reveal that the eagle’s syndrome is not rare like previously thought. In contrast to widely reported in world literature, investigations over Eagle’s syndrome in the under-18 population must be strongly considered. The hypothesis raised here is that the idea that the syndrome affects only the adult population seems to be misguided, and it may be resulted from underreporting in underage patients. The clinical exam without considering some symptoms like neuralgia and facial/cervical pain or discomfort could hide a possible calcification of styloid ligament as being the stimulator factor. This hypothesis is supported by the few reports of occurrence of this condition in children, such as the notifications by Holloway and cols in 1991, and Quereshy and cols in 2001, who have reported the Eagle’s syndrome in a 5-years-old and a 11-year-old respectively.

It is believed that the elongation of styloid process could be a late consequence of a tonsillectomy as a cervical trauma, leading to a responsive hyperplasia or metaplasia [26] of the styloid process, or maybe only an anatomical variation [26,27], which should explain this condition in children. Furthermore, the first one lead us to think that an inflammation onto surrounding tissues of hyoid apparatus could be unleash a cell metaplasia and then turns the calcification on ligament; however, this pathophysiological mechanism seems to be low incidence. Regarding the low prevalence in the 70 and 99 age group revealed by our results, we can notice here that this mechanism does not follow the well-known physiological pattern of aging in which there is a remarkable trend for calcification of many joints of human body, such as the synostosis in the skull sutures or even the bone spicules surrounding the intervertebral discs being exacerbated with the sedentary lifestyle. These ideas open up spaces for several scientific investigations to be held to unravel the pathophysiology of the calcification of styloid ligament and the clinical consequences of the elongation of styloid process.

Conclusion

Eagle’s syndrome is a poorly known and misunderstood condition by clinicians, and it is not a truly rare syndrome. Our research revealed that it is more common between the second and sixth decades of life in a Brazilian population. Also, a higher prevalence in men, usually in the bilateral condition, and the right side predominantly over the left one. We would like to stress here that further research is needed to clear its ethology and physiopathology of the syndrome. This condition should be clearly comprehended by professionals, and then new management and approach protocols could be designed when facing patients, from

Acknowledgement

The authors thank CNPq (National Council for Scientific and Technological Development), and the Directory of Research of the Federal University of Uberlandia.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Chrcanovic BR, Custodio AL, De Oliveira DR (2009) An intraoral surgical approach to the styloid process in Eagle’s syndrome. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 13(3): 145-151.

- Kim E, Hansen K, Frizzi J (2008) Eagle syndrome: case report and review of the literature. Ear, Nose & Throat Journal 87(11): 631-633.

- Eagle WW (1958) Elongated styloid process. Archives of Otolaryngology 67: 172-176.

- Kawai T, Shimozato K, Ochiai S (1990) Elongated styloid process as a cause of difficult intubation. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 48(11): 1225-1228.

- Keur JJ, Campbell JPS, McCarthy JF, Ralph WJ (1986) The clinical significance of the elongated styloid process. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology 61(4): 399-404.

- Czako L, Simko K, Thurzo A, Galis B, Varga I (2020) The syndrome of elongated styloid process, the Eagle’s Syndrome from anatomical, evolutionary, and embryological backgrounds to 3D printing and personalized surgery planning. Report on five cases. Medicina 56(9): 458-467.

- Quereshy F, Gold E, Arnold J, Powers MP (2001) Eagle’s syndrome in an 11-year-old patient. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 59(1): 94-97.

- Shereen R, Gardner B, Altafulla J, Simonds E, Iwanag J, et al. (2019) Pediatric glossopharyngeal neuralgia: a comprehensive review. Child’s Nervous System 35(3): 395-402.

- Goomany A, Shayah A, Adams B, Coatesworth A (2020) Eagle syndrome: elongated stylohyoid associated facial pain. BMJ Case Reports 13(3): e234024.

- Pace A, Rossetti V, Ianella G, Magliulo G (2020) Unusual symptomatology in Eagle syndrome. Clinical Medicine Insights: Case Reports 13: 1-2.

- Rizzatti Barbosa CM, Ribeiro MC, Silva Concilio LR, Di Hipolito O (2005) Is an elongated stylohyoid process prevalent in the elderly? A radiographic study in a Brazilian population. Gerodontology 22(2): 112-115.

- Sokler K, Sandev S (2001) New classification of the styloid process length clinical application on the biological base. Collegium Antropologicum 25(2): 627-632.

- Fortes LHS, Bordoni LS (2017) Eagle Syndrome produced by a carotid sleeper hold strangulation case report and forensic medicine considerations. Brazilian Journal of Forensic Science, Medical Law, and Bioethics 7(1): 23-34.

- Guimaraes AGP, Cury EV, Silva MBF, Junqueira JLC, Torres SCM (2010) Prevalence of elongated styloid process and/or ossified stylohyoid ligament in panoramic radiographs. Revista Gaucha de Odontologia 58(4): 481-448.

- Costa RS, Fontanella VRC (2014) Anatomical changes of the styloid process in a Brazilian subpopulation. Journal of Dental Health and Oral Disorder Therapy 1(1): 15-18.

- Cohn JE, Othman S, Sajadi Ernazarova K (2020) Eagle syndrome masquerading as a chicken bone. International Journal of Emergency Medicine 13(1): 1.

- Bruno G, De Stefani A, Barone M, Costa G, Saccomanno S, et al. (2019) The validity of panoramic radiograph as a diagnostic method for elongated styloid process: A systematic review. Cranio: The Journal of Craniomandibular and Sleep Practice 9: 1-8.

- Kaufman SM, Elzay RP, Irish EF, Richmond V (1970) Styloid process variation: Radiological and clinical study. Archives of Otolaryngology 91(5): 460-463.

- AlZarea BK (2017) Prevalence and pattern of the elongated styloid process among geriatric patients in Saudi Arabia. Clinical Interventions in Aging 12: 611-617.

- Munoz Leija MA, Ordonez Rivas FO, Barrea Flores FJ, Trevino Gonzalez JL, Pinales Razo R, et al. (2020) A proposed extension to the elongated styloid process definition: A morphological study with high-resolution tomography computer. Morphologie 104(345): 117-124.

- Phulambrikar T, Rajeshwari A, Rao BB, Warhekar AM, Reddy P (2011) Incidence of elongated styloid process: a radiographic study. Journal of Indian Academy of Oral Medicine and Radiology 23(3): 344-346.

- Wong ML, Rossi MD, Groff W, Castro S, Powell J (2011) Physical therapy management of a patient with Eagle syndrome. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 27(4): 319-327.

- Roopashri G, Vaishali MR, David MP, Baig M, Shankar U (2012) Evaluation of elongated styloid process on digital panoramic radiograph. The Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice 13(5): 618-622.

- Scaf G, Freitas DG, Loffredo LC (2003) Diagnostic reproducibility of the elongated styloid process. Journal of Applied Oral Science 11(2): 120-124.

- Goomany A, Shayah A, Adams B, Coatesworth A (2020) Eagle syndrome: elongated stylohyoid- associated facial pain. BMJ Case Reports 13(3): e234024.

- Piagkou M, Anagnostopoulou S, Kouladouros K, Piagkos G (2009) Eagle’s syndrome: a review of the literature. Clinical Anatomy 22(5): 545-558.

- Steinmann EP (1968) Styloid syndrome in absence of an elongated process. Acta Oto-Laryngologica 66(4): 347-356.

- Badhey A, Jategaonkar A, Kovacs AJA, Kadakia S, De Deyn PP, et al. (2017) Eagle syndrome: a comprehensive review. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery 159: 34-38.

- Gupta A, Aggrawal A, Setia P (2017) A rare fatality due to calcified stylohyoid ligament (Eagle syndrome). Medico Legal Journal 85(2): 103-104

- Holloway M, Wason S, Willging J, Myer CR, Wood B (1991) Radiological case of the mouth. A pediatric case of Eagle’s syndrome. The American Journal of Diseases of Children 3: 339-340.

-

Anny Isabelly dos Santos Souza, João César Guimarães Henriques, Fabio Franceschini Mitri*. Epidemiological Study of the Eagle’s Syndrome Through Panoramic Radiographs of Adults from A Brazilian Population. Arch Clin Case Stud. 3(2): 2022. ACCS. MS.ID.000560.

-

Bony cylindrical, Odynophagia, Panoramic radiographs, Styloid process, Radiographic finding

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.