Case Report

Case Report

Atypical Onset of Tics and Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms in FXTAS Following COVID-19: A Case Report

E Rolleri1,2,3, V Liani1,4, NA Yusoff1,5, N Likhitweeraeong1,6, S Moore1, F Tassone1,7, A Schneider1,8, E Santos1,8, JA Bourgeois9 and, RJ Hagerman1,8*

1Medical Investigation of Neurodevelopmental Disorders (MIND) Institute, University of California, Davis Health, Sacramento CA, USA

2Life Sciences and Public Health Department, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Rome, Italy

3Child & Adolescent Neuropsychiatry Unit, Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital, IRCCS, Rome, Italy

4Department of Women’s and Children’s Health, University of Padova, Padova, Italy

5Department of Pediatric, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University Putra Malaysia, Seri Kembangan, Selangor, Malaysia

6Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand

7Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Medicine, School of Medicine, University of California, Davis, Davis CA, USA

8Department of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, University of California, Davis, Sacramento CA, USA

9Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of California, Davis Medical Center, Sacramento CA, USA

Randi J Hagerman, Medical Investigation of Neurodevelopmental Disorders (MIND) Institute, University of California, USA

Received Date: October 19, 2024; Published Date: January 22, 2025

Abstract

Individuals with premutation alleles of the FMR1 gene typically exhibit normal cognitive abilities in early and mid-life, unlike those with fragile X syndrome. However, as they age, approximately 40% of male and 16% of female carriers develop fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS). This neurodegenerative disorder is characterized by an intention tremor, cerebellar ataxia, and psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety, depressive, and neurocognitive disorders. While data on the impact of COVID-19 on FXTAS is still limited, examining this interaction is critical, given the widespread nature of the virus. In this case report, we describe a male premutation carrier with FXTAS who experienced an abrupt progression of motor and vocal tics along with obsessive-compulsive symptoms and cognitive decline following COVID-19 infection. This case suggests a potential link between the infection and the rapid onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms in a FXTAS patient, raising important questions regarding the involvement of immune responses in this interaction.

Keywords: Fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome; FXTAS; premutation; tics; obsessive-compulsive disorder; COVID-19; FMR1

Abbreviations: Pm: premutation; FXS: Fragile X Syndrome; FMR1 gene: Fragile X Messenger Ribonucleoprotein 1; FXAND: fragile X-associated neuropsychiatric disorders; FXTAS: Fragile X-Associated Tremor/Ataxia Syndrome; OCD: obsessive-compulsive disorder; MCP: middle cerebellar peduncle; TS: Tourette syndrome; PCR: Polymerase Chain Reaction; qRT-PCR: Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; WAIS IV: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale IV; MoCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment; FSIQ: Full Scale Intelligence Quotient; VCI: Verbal Comprehension Index; WMI: Working Memory Index; POI: Perceptual Organization Index; PSI: Processing Speed Index: Montreal Cognitive Assessment; BDS-2: Behavioral Dyscontrol Scale; SCID: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM; CNS: Central Nervous System; PANS: Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome.

Introduction

Individuals carrying premutation (PM) alleles (55–200 CGG repeats) of the fragile X messenger ribonucleoprotein 1 (FMR1) gene typically exhibit normal cognitive abilities in early and midlife, unlike the childhood onset intellectual disability associated with fragile X syndrome (FXS). However, psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety, depression, and neurocognitive disorders, are common in these individuals from mid-life onward, affecting approximately 50% of premutation carriers [1]. These psychiatric co-morbidities are collectively referred to as fragile X-associated neuropsychiatric disorders (FXAND). While anxiety disorders are the most prevalent psychiatric co-morbidities among PM carriers, other associated conditions include depressive disorders, insomnia, obsessivecompulsive disorder (OCD), chronic pain, chronic fatigue syndrome, and late onset neurocognitive disorders [1,2]. As PM carriers age, between 40 to 75% of males and 16% of females [2,3], may develop fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS), a late-onset neurodegenerative disorder. FXTAS is characterized by gait ataxia, intention tremors, neuropathy, cognitive decline, and co-morbid psychiatric complications.

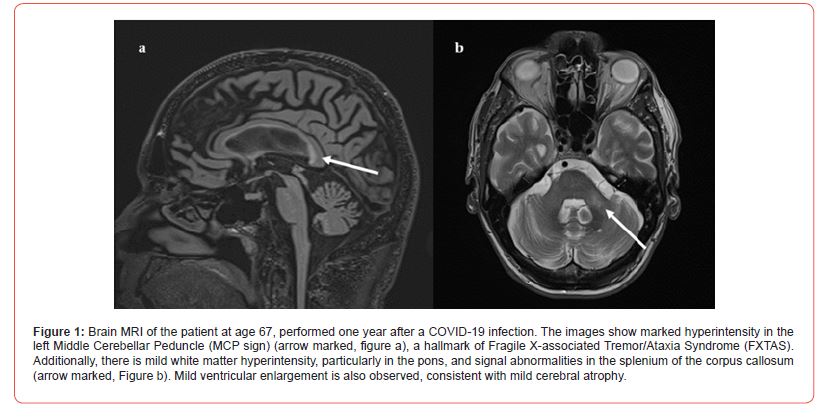

The diagnosis of FXTAS requires MRI imaging to identify white matter changes, including the middle cerebellar peduncle (MCP) sign, which is present in approximately 60% of males and 10% of females with FXTAS and is highly specific for FXTAS [4- 6]. In contrast, females are more likely to show white matter abnormalities in the splenium of the corpus callosum, Schneider et al reported a probability greater than 60% for women with FXTAS to present with high‐signal intensity in the splenium [6], though both genders may have the splenium sign and periventricular white matter disease [2,7,8]. Patients with the premutation may begin to exhibit symptoms of FXTAS in their 50s to 60s, with its prevalence increasing significantly with age. Around 38% of males in their 60s are affected, rising to as much as 75% by their 80s. Symptoms usually begin insidiously, with tremor as the initial sign, followed by balance difficulties and peripheral neuropathy in the lower extremities. Major neurocognitive disorder/dementia develops in approximately 50% of males with FXTAS but is less common in females, who also tend to experience a slower progression of the disease [8,9].

Motor and vocal tics, along with other involuntary movements, are not part of the recognized FXTAS phenotype. It is rare for tic disorders to emerge after the second decade of life. Typically, they first manifest during childhood, and in most cases, their severity decreases during adolescence, often reaching mild or minimal levels by early adulthood [10]. However, for some patients, tics do not follow this typical pattern and can persist, sometimes remaining severe well into adulthood [11]. Additionally, there are reports of Tourette syndrome (TS)-like symptoms emerging later in life, often because of neurological conditions such as stroke, encephalitis, or after exposure to certain medications [12-14]. Several characteristics are associated with tics. One of them is the feeling of an urge to perform the movement (premonition urge) with a transient sense of relief after the tic is performed. Tics are often voluntarily suppressible, though suppressing them usually comes with a feeling of discomfort, at least transiently [10,15]. Similarly, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is not among the psychiatric co-morbidities with FXTAS, although it falls within the spectrum of disorders under the FXAND umbrella [16,17].

Moreover, it is infrequent for OCD to first present later in life. OCD typically begins in childhood, frequently associated with TS, though OCD onset after the age of 30 has been reported in 11.3% of those adults with a lifetime diagnosis of OCD. [18,19]. OCDlike symptoms have also been reported in Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and frontotemporal dementia, where cognitive decline and executive dysfunction may lead to obsessive thoughts and associated compulsive actions [20,21]. In this report, we describe a patient in the early stages of FXTAS, presenting very mild motor symptoms and white matter disease, who experienced an acute/subacute onset of executive dysfunction, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and motor and vocal tics following a COVID-19 infection. The notable aspects of our case include the rapid onset of symptoms, the presence of tics and compulsive behaviors, and the potential role of COVID-19 infection in triggering these phenomena. The patient provided informed consent for both neuropsychological/motor and molecular testing, as approved by the institutional IRB of the University of California Davis Health Center. He also consented to the publication of his case history. All relevant information was gathered through a review of clinic visit notes and previous reports.

Case Presentation

The patient was a 67-year-old Caucasian male with a premutation allele of the FMR1 gene with 84 CGG repeats, as measured by PCR and Southern blot analysis [22,23] and an FMR1 mRNA level 2.2- fold higher that in the general population, as measured by qRTPCR as previously described [24]. His family history was notable for a brother who was also a premutation carrier, as well as two daughters and nieces with premutation carrier status. There was a significant family history of sudden cardiac death on his paternal side and of cancer on both sides of the family, but no known family history of tics or OCD. He denied any prior psychiatric (including neurocognitive) disorders, describing himself only as a “slow test taker” in school. Despite this, he completed medical school, then residency and fellowship in radiology, establishing a successful career in medicine. His medical history included high-frequency hearing loss in his left ear and reduced vibratory sensation in his left great toe, both detected at 25 years of age. At age 55, he was diagnosed with hemochromatosis and deep vein thrombosis, for which he had been treated with coumadin and aspirin.

At age 60, he developed bilateral uveitis and was treated with methylprednisolone. He denied other autoimmune disorders. At age 60 he also developed a subclinical tremor that was slightly more severe in his left upper extremity. Brain MRI at that time revealed high intensity T2 signals in the middle cerebellar peduncles (left greater than right) as well as mild white matter disease. Although he was immunized against COVID-19, at age of 66, the patient contracted a prolonged and severe COVID-19 infection, with fever, malaise, prolonged fatigue, and cough. He was not hospitalized, and he was ill for approximately 6 weeks, but upon recovery, his wife, a pediatrician, reported observing the sudden onset of involuntary movements in his left upper extremity that were ticlike. These movements subsided within a few weeks, but he soon began to experience motor restlessness plus persistent cognitive difficulties including trouble with concentration and challenges in task prioritization. Additionally, episodes were reported where he struggled with organizing and communicating his thoughts.

He also exhibited difficulties with time management and a tendency toward obsessive thinking, characterized by excessive attention to details and a need for tasks to be performed in a specific ritualistic way. He reported that professional tasks like reviewing MRI images, which previously took him half an hour, now required several hours to complete. About three months later, the patient reported the reoccurrence of motor tics, primarily affecting his neck, trunk, and his left upper extremity, and vocal tics, characterized by spontaneous vocalizations and occasional changes in vocal tone. He described being able to suppress these involuntary movements and vocalizations but doing so caused unpleasant sensations and a persistent urge to perform the tics. Both the cognitive difficulties and the tic disorder had acute onset and remained stable over time, interfering with his work as a radiologist, leading to his retirement. At his most recent examination, his condition was stable. He was taking hydrochlorothiazide, folate, DHA, vitamin D, magnesium, curcumin, CoQ10, and lutein. He reported only mild positional tremors and denied balance problems, although he experienced occasional falls while hiking.

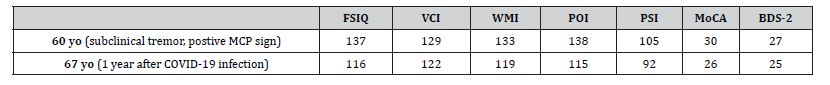

He also reported a persistent feeling of numbness, tingling and reduced sensitivity in his feet. Upon examination, his cranial nerves were intact, except he demonstrated significant bilateral hearing loss, which appeared to have increased since the last assessment, with an estimated 70% reduction. Muscle strength was normal throughout. Deep tendon reflexes were asymmetrical, with 1+ on the right and 2+ on the left biceps, 1+ at the knees, and absent at the ankles. The vibration sense was absent on the left foot and decreased on the right foot. There was an increased muscle tone in his left upper limb, while the right upper limb remained normal. Fingerto- nose testing revealed a subtle, subclinical intention tremor bilaterally. Primitive reflexes were absent, and his gait was normal. During tandem walking, he was able to maintain balance, though the mis stepped after six steps. Neuropsychological tests, such as Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), subtests of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) IV, and the Behavioral Dyscontrol Scale (BDS-2), revealed a primary deficit in psychomotor speed accompanied by secondary weaknesses in aspects of executive functioning and information processing efficiency (Table 1).

Although the patient’s performance metrics did not indicate clinical impairment, the discrepancy from his previously wellabove- average functioning reflected a marked decline in cognitive efficiency, processing speed, and executive functioning, consistent with his reported subjective complaints. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (SCID) met no clinical criteria, although increased tangential speech patterns were noted. Given the presence of OCDlike behaviors and tics, treatment with an SSRI, such as sertraline or fluoxetine, was recommended (Table 1). Comparison of the most recent brain MRI with the MRI from 7 years previously revealed further increased hyperintensity in the left middle cerebellar peduncle (MCP sign) and enhanced diffuse deep white matter changes, particularly in the pons. Additionally, new high-signal intensity was noted in the splenium of the corpus callosum, which was absent in the earlier scan. There was also evidence of mild cortical atrophy with associated ventricular dilation (Figure 1).

Table 1: Neurocognitive assessments before and after COVID-19 infection on WAIS IV and MoCA. FSIQ: Full Scale Intelligence Quotient; VCI: Verbal Comprehension Index; WMI: Working Memory Index; POI: Perceptual Organization Index; PSI: Processing Speed Index; MoCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment; BDS-2: Behavioral Decontrol Scale; MCP: Middle Cerebellar Peduncle.

Discussion

The onset of tics and obsessive-compulsive symptoms following COVID-19 infection in individuals with FXTAS has not been previously reported, although OCD symptoms are relatively common in premutation females. Clearly, the COVID-19 infection had effects on the Central Nervous System (CNS) either through direct infection of his brain or through secondary immunological effects, such as CNS antibodies stimulated by the virus. Adding to this presentation are the patient’s neuroimaging findings, where two main features stand out. First is the asymmetrical T2 hyperintensity of the cerebellar peduncles, with greater involvement of the left (Figure 1). This is the opposite of what would have been expected, which was a contralateral involvement with respect to the motor symptoms. This hyperintensity had increased since it was initially detected in 2022, predating the current psychiatric symptoms, but appearing concurrently with the tremor in his left hand. Notably, previous neuroradiological studies on Tourette syndrome have frequently shown altered cerebellar connectivity [25,26]. The second prominent feature was the pronounced hyperintensity of the splenium of the corpus callosum.

Splenium hyperintensity is a hallmark of FXTAS and has been implicated in both executive dysfunction as well as in OCD [27,28]. Koch et al. reported that the corpus callosum is one of the most affected structures in OCD patients, with alterations in white matter integrity observed in both adults and adolescents [29-31]. What distinguishes this case is the abrupt onset of symptoms, which shifts our focus away from FXTAS as the primary cause and suggests a role for autoimmune dysregulation. All symptoms appeared suddenly following a COVID-19 infection. In Pediatric patients, such combination of neuropsychiatric symptoms, acute onset, and recent infection might lead to a diagnosis of Pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS). Although this diagnosis remains controversial, there have been a few reports of PANS-like presentations following COVID-19, albeit exclusively in Pediatric populations [32,33]. The neurotropic properties of COVID-19 are also well-documented and likely to play a role here. The psychiatric manifestations in COVID-19 patients range from cognitive impairment to psychosis, with even non-hospitalized patients with mild cases showing declines in cognitive function [34].

Additionally, COVID-19 has been linked to the onset or acceleration of neurodegenerative disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and multiple sclerosis [35-37]. These effects may stem from immune system dysregulation, a mechanism implicated in a proposed subtype of OCD that is also central to the pathophysiology of FXTAS [2,38]. Plasma metabolic profiles of FXTAS premutation carriers have revealed evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction, neurodegeneration markers, and proinflammatory damage. Additionally, FXTAS is known to involve the activation of microglia and astrocytes, along with elevated levels of specific cytokines in the brain [2,39]. What is not unusual in this case is the presence of executive function deficits, which is the cognitive domain most affected in premutation carriers [40,41]. However, these deficits appear to be temporally related to and putatively exacerbated by COVID-19 infection, suggesting acute damage to the CNS leading to this symptom exacerbation. A critical question is whether his tics were anatomically correlated.

Most of the literature on late-onset tic disorders suggests that tics emerging after adolescence cannot be anatomically or physiologically correlated, suggesting that the symptoms might be associated with psychological distress [42-44]. The patient, however, exhibited clinical characteristics typically associated with anatomically correlated tics. He reported a premonitory urge preceding the tics, followed by a sense of relief after performing them, and was able to exert some control over the tics, albeit with discomfort. In conclusion, this case presents a notable intersection among FXTAS, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and post-COVID-19 sequelae. This highlights the need for further investigation into the possible mechanisms underlying late-onset tics and obsessivecompulsive symptoms in the context of neurodegenerative disorders. The atypical rapid symptom onset following COVID-19 infection, combined with the uncommon symptom profile, raises important questions about the role of immune dysregulation.

These immune responses may be impacted by the RNA toxicity of FXTAS causing mitochondrial dysfunction and the greater number of autoimmune problems seen in women with the premutation with or without FXTAS [39]. However, the COVID-19 infection likely exacerbated CNS inflammation which is also known to be present in FXTAS [2]. Overall, the FXTAS brain is likely more vulnerable to the neuroinflammation and autoimmune response to this virus leading to the faster emergence of executive dysfunction that is characteristic of FXTAS. Further neuroimaging and longitudinal follow-up will be crucial in understanding the potential interplay between FXTAS progression and post-infectious neuropsychiatric complications, as well as determining the most appropriate management strategies for such complex cases.

Acknowledgement

This research was funded by NICHD HD036074 and by the MIND Institute IDDRC funded by NICHD P50 HD 103526.

Conflict of Interest

RJH has received funding from Zynerba Pharmaceuticals and Tetra/Shinogoi for clinical trials in those with Fragile X syndrome. JAB is funded by Abbott for research in deep brain stimulation for depressive disorders and receives royalties from various medical publishers.

References

- Hagerman RJ, Protic D, Rajaratnam A, Salcedo-Arellano MJ, Aydin EY, et al. (2018) Fragile X-Associated Neuropsychiatric Disorders (FXAND). Front Psychiatry 9: 564.

- Flora Tassone, Dragana Protic, Emily Graves Allen, Alison D Archibald, Anna Baud, et al. (2023) Insight and Recommendations for Fragile X-Premutation-Associated Conditions from the Fifth International Conference on FMR1 Cells 12(18): 2330.

- Sébastien Jacquemont, Randi J Hagerman, Maureen A Leehey, Deborah A Hall, Richard A Levine, et al. (2004) Penetrance of the fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome in a premutation carrier population. JAMA 291(4): 460-469.

- Leehey MA (2009) Fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome: clinical phenotype, diagnosis, and treatment. J Investig Med 57(8): 830-836.

- Brunberg JA, Jacquemont S, Hagerman RJ, Berry-Kravis EM, Grigsby J, et al. (2002) Fragile X premutation carriers: characteristic MR imaging findings of adult male patients with progressive cerebellar and cognitive dysfunction. AJNR Am J Neuroadial 23(10): 1757-1766.

- Schneider A, Summers S, Tassone F, Seritan A, Hessl D, et al. (2020) Women with fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. Mov Disord Clin Pract 7(8): 910-919.

- Wang J, Napoli E, Kim K, McLennan YA, Hagerman RJ, et al. (2021) Brain atrophy and white matter damage linked to peripheral bioenergetic deficits in the neurodegenerative disease FXTAS. Int J Mol Sci 22(17): 9171.

- Cabal-Herrera AM, Tassanakijpanich N, Salcedo-Arellano MJ, Hagerman RJ (2020) Fragile x-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS): pathophysiology and clinical implications. Int J Mol Sci 21(12): 4391.

- Johnson D, Santos E, Kim K, Ponzini MD, McLennan YA, et al. (2022) Increased Pain Symptomatology Among Females vs. Males with Fragile X-Associated Tremor/Ataxia Syndrome. Front Psychiatry 12: 762915.

- Black KJ, Kim S, Yang NY, Greene DJ (2021) Course of tic disorders over the lifespan. Curr Dev Disord Rep 8(2): 121-132.

- Bloch MH, Leckman JF (2009) Clinical course of tourette syndrome. J Psychosom Res 67(6): 497-501.

- Mejia NI, Jankovic J (2005) Secondary tics and tourettism. Braz J Psychiatry 27(1): 11-17.

- Rohani M, Fasano A, Lang AE, Zamani B, Javanparast L, et al. (2018) Pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration mimicking tourette syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. Neurol Sci 39(10): 1797-1800.

- Kim DD, Barr AM, Chung Y, Yuen JWY, Etminan M, et al. (2018) Antipsychotic-associated symptoms of tourette syndrome: a systematic review. CNS Drugs 32(10): 917-938.

- Ueda K, Black KJ (2021) A comprehensive review of tic disorders in children. J Clin Med 10(11): 2479.

- Schneider A, Johnston C, Tassone F, Sansone S, Hagerman RJ, et al. (2016) Broad autism spectrum and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in adults with the fragile X premutation. Clin Neuropsychol 30(6): 929-943.

- Aishworiya R, Protic D, Tang SJ, Schneider A, Tassone F, et al. (2022) Fragile x-associated neuropsychiatric disorders (FXAND) in young fragile x premutation carriers. Genes (Basel) 13(12): 2399.

- Grant JE, Mancebo MC, Pinto A, Williams KA, Eisen JL, et al. (2007) Late-onset obsessive compulsive disorder: clinical characteristics and psychiatric comorbidity. Psychiatry Res 152(1): 21-27.

- Stein DJ, Costa DLC, Lochner C, Miguel EC, Reddy YCJ, et al. (2019) obsessive-compulsive disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers 5(1): 52.

- Ruggeri M, Ricci M, Gerace C, Blundo C (2022) Late-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder as the initial manifestation of possible behavioural variant Alzheimer's disease. Cogn Neuropsychiatry 27(1): 11-19.

- Frileux S, Millet B, Fossati P (2020) Late-onset OCD as a potential harbinger of dementia with Lewy bodies: A report of two cases. Front Psychiatry 11: 554.

- Tassone F, Pan R, Amiri K, Taylor AK, Hagerman PJ (2008) A rapid polymerase chain reaction-based screening method for identification of all expanded alleles of the fragile X (FMR1) gene in newborn and high-risk populations. J Mol Diagn 10(1): 43-49.

- Filipovic-Sadic S, Sah S, Chen L, Krosting J, Sekinger E, et al. (2010) A novel FMR1 PCR method for the routine detection of low abundance expanded alleles and full mutations in fragile X syndrome. Clin Chem 56(3): 399-408.

- Tassone F, Hagerman RJ, Taylor AK, Gane LW, Godfrey TE, et al. (2000) Elevated levels of FMR1 mRNA in carrier males: a new mechanism of involvement in the fragile-X syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 66(1): 6-15.

- Caligiore D, Mannella F, Arbib MA, Baldassarre G (2017) Dysfunctions of the basal ganglia-cerebellar-thalamo-cortical system produce motor tics in Tourette syndrome. PLoS Comput Biol 13(3): e1005395.

- Worbe Y, Lehericy S, Hartmann A (2015) Neuroimaging of tic genesis: present status and future perspectives. Mov Disord 30(9): 1179-1183.

- Jokinen H, Ryberg C, Kalska H, Ylikoski R, Rostrup E, et al. (2007) Corpus callosum atrophy is associated with mental slowing and executive deficits in subjects with age-related white matter hyperintensities: the LADIS Study. Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 78(5): 491-496.

- Silk T, Chen J, Seal M, Vance A (2013) White matter abnormalities in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res 213(2): 154-160.

- Garibotto V, Scifo P, Gorini A, Alonso CR, Brambati S, et al. (2010) Disorganization of anatomical connectivity in obsessive compulsive disorder: a multi-parameter diffusion tensor imaging study in a subpopulation of patients. Neurobiol Dis 37(2): 468-476.

- Zarei M, Mataix-Cols D, Heyman I, Hough M, Doherty J, et al. (2011) Changes in gray matter volume and white matter microstructure in adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry 70(11): 1083-1090.

- Koch K, Reess TJ, Rus OG, Zimmer C, Zaudig M (2014) Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) studies in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): a review. J Psychiatr Res 54: 26-35.

- Berloffa S, Salvati A, Pantalone G, Falcioni L, Rizzi MM, et al. (2023) Steroid treatment response to post SARS-CoV-2 PANS symptoms: case series. Front Neurol 14: 1085948.

- Ayşegül Efe (2022) SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 associated pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome a case report of female twin adolescents. Psychiatry Res Case Rep 1(2): 100074.

- Antonio de Pádua Serafim, Saffi F, Soares ARA, Morita AM, Assed MM, et al. (2024) Cognitive performance of post-covid patients in mild, moderate, and severe clinical situations. BMC psychology 12(1): 236.

- Michelena G, Casas M, Eizaguirre MB, Pita MC, Cohen L, et al. (2022) Can COVID-19 exacerbate multiple sclerosis symptoms? A case series analysis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 57: 103368.

- Mysiris DS, Vavougios GD, Karamichali E, Papoutsopoulou S, Stavrou VT, et al. (2022) post-COVID-19 parkinsonism and parkinson's disease pathogenesis: the exosomal cargo hypothesis. Int J Mol Sci 23(17): 9739.

- Dubey S, Das S, Ghosh R, Dubey MJ, Chakraborty AP, et al. (2023) The effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the cognitive functioning of patients with pre-existing dementia. J Alzheimers Dis Rep 7(1): 119-128.

- Endres D, Pollak TA, Bechter K, Denzel D, Pitsch K, et al. (2022) Immunological causes of obsessive-compulsive disorder: is it time for the concept of an "autoimmune OCD" subtype? Transl Psychiatry 12(1): 5.

- Winarni TI, Chonchaiya W, Sumekar TA, Ashwood P, Morales GM, et al. (2012) Immune-mediated disorders among women carrier of fragile X premutation alleles. Am J Med Genet Part A (10): 2473-2481.

- Hessl D, Mandujano Rojas K, Ferrer E, Espinal G, Famula J, et al. (2024) FMR1 carriers report executive function changes prior to fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome: a longitudinal study. Mov Disord 39(3): 519-525.

- Grigsby J, Brega AG, Leehey MA, Goodrich GK, Jacquemont S, et al. (2007) Impairment of executive cognitive functioning in males with fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. Mov Disord 22(5): 645-650.

- Jack RH, Joseph RM, Coupland CAC, Hall CL, Hollis C (2023) Impact of the covid-19 pandemic on incidence of tics in children and young people: A population-based cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 57: 101857.

- Pringsheim T, Ganos C, McGuire JF, Hedderly T, Woods D, et al. (2021) Rapid onset functional tic-like behaviors in young females during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mov Disord 36(12): 2707-2713.

- Han VX, Kozlowska K, Kothur K, Lorentzos M, Wong WK, et al. (2022) Rapid onset functional tic-like behaviours in children and adolescents during COVID-19: Clinical features, assessment, and biopsychosocial treatment approach. J Paediatr Child Health 58(7): 1181-1187.

-

E Rolleri, V Liani, NA Yusoff, N Likhitweeraeong, S Moore, F Tassone, A Schneider, E Santos, JA Bourgeois and, RJ Hagerman*. Atypical Onset of Tics and Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms in FXTAS Following COVID-19: A Case Report. Arch Clin Case Stud. 4(4): 2025. ACCS.MS.ID.000589.

-

Fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome; FXTAS; premutation; tics; obsessive-compulsive disorder; COVID-19; FMR1

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.