Mini Review

Mini Review

ABCD…Airway, Breathing, Circulation (and don’t forget Differentials)

Chris R Darby1, Katherine Hurst1,2 and Ashok Handa1,2*

1Department of Vascular Surgery, John Radcliffe Hospital, UKt

2Nuffield Department of Surgical Sciences, University of Oxford, UK

Ashok Handa, Nuffield Department of Surgical Sciences, University of Oxford, UK.

Received Date: June 16, 2020; Published Date: July 06, 2020

Abstract

Male patients over the age of 65, presenting with acute abdominal pain should be managed as a potential ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), until proven otherwise. Ruptured AAA is a commonly missed life-threatening diagnosis. This paper aims to recap over the diagnosis and management to aid doctors in training in their decision making.

Keywords:AAA; Aneurysm; Rupture; Epigastric pain; Collapse

Main Text

History

A 69-year old man presented to the emergency department with a three-week history of general malaise and diarrhoea, on a background of chronic kidney disease (baseline creatinine 250 μmol/L) and an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA;5cm). He was admitted with acute kidney injury (creatinine 1500 μmol/L) presumed to be secondary to severe hypovolemia, and commenced emergently on hemofiltration requiring heparinization, as well as aggressive fluid resuscitation. A few days later, he developed sudden onset of epigastric pain and syncope, with increasing abdominal girth and decreasing haemoglobin. Surgical review found a tender abdomen with a pulsatile epigastric mass, however he continued to be hydrated and anti-coagulated, as definitive diagnostic imaging and vascular referral was delayed until the following morning, some 5 hours later.

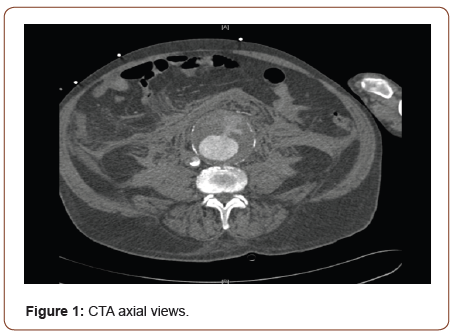

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) of the abdomen showed a large infrarenal AAA, measuring 7.5 cm in maximal anterior-posterior diameter (Figures 1 & 2). Typical features of an aortic aneurysm include the calcified intimal layer of the arterial wall and the eccentric thrombus lining of the arterial lumen.

Of greater concern is the presence of an apparent contained rupture indicated by the presence of a significant retroperitoneal swelling due to a large contained haematoma, in this case unusually bilaterally and anteriorly displacing the posterior peritoneum; this can be verified by indicative Hounsfield’s units [1]. Quite remarkably, contrast can also be seen jetting from the intraluminal space into the haematoma anteriorly. The former is sufficient to demonstrate a ruptured aneurysm that has subsequently tamponaded, however the latter suggests ongoing bleeding into the retroperitoneal space.

Key Points

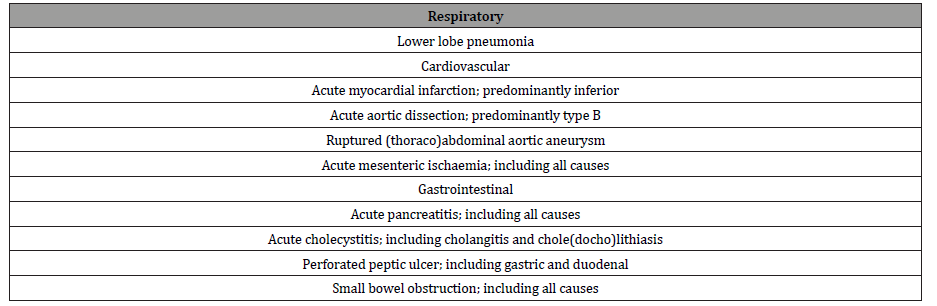

This case demonstrates that a high index of suspicion must always be exercised when patients over 65-years present with a history of epigastric pain and collapse. Certainly, a ruptured aneurysm constitutes one of several important differentials that must always be suspected and rapidly excluded (Table 1). In this case, a ruptured AAA could have been seen using a bedside ultrasound, including a FAST (focused assessment with sonography for trauma) scan [2]. Otherwise, in the setting of such severe acute renal failure, even a non-contrast CT would have sufficient features to suggest the diagnosis.

Management

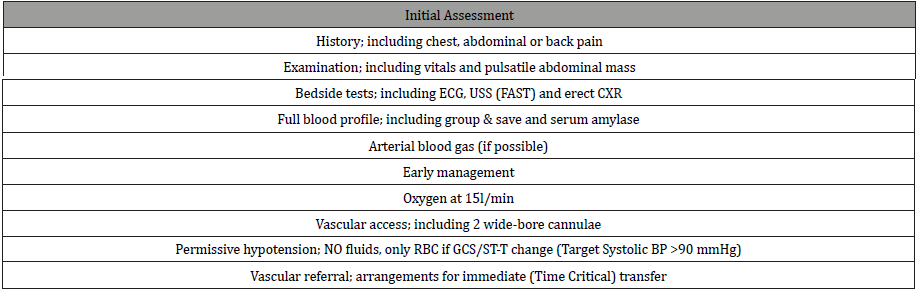

Management of ruptured aneurysms includes early assessment and management with subsequent rapid access to definitive treatment (Table 2). If suspected or confirmed, all patients should have adequate vascular access, and “permissive hypotension” is key, such that low systolic blood pressures (>90mmHg) are tolerated as long as the Glasgow Coma Scale remains 15 and ST-T segment remains unchanged on electrocardiography. If the patient becomes haemodynamically unstable, volume resuscitation should be implemented cautiously with packed red blood cells, either previously cross-matched or O-negative if a crossmatch is not available. Simultaneously, early referral and rapid transfer to the nearest Vascular Unit should be facilitated [3].

Table 1: Differentials of common causes of epigastric pain and collapse in patients over the age of 65-years requiring emergent diagnosis and management.

Table 2: Suggested approach to initial assessment of epigastric pain and collapse, and early management of suspected ruptured AAA [3].

Our patient remained incredibly haemodynamically stable, despite significant delays in the diagnosis and transfer, as well as ongoing and potentially compromising intercurrent medical management. He was transferred from a neighbouring District Hospital to the John Radcliffe Hospital via road ambulance. He was immediately taken to the operating theatre, where he underwent open repair with infrarenal clamps and tube graft replacement of the aneurysmal section. He required further hemofiltration during his 3 day stay in the intensive care unit, and intermittent haemodialysis for a further 10 days until discharge.

Note

As with all patients with AAA, he was screened for popliteal aneurysms and advised that all first-degree male relatives over the age of 50 years should be screened for an AAA with abdominal ultrasound.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No Conflicts of Interest.

References

- Roy J, Labruto F, Beckman MO, Jesper Danielson, Gunnar Johansson, et al. (2008) Bleeding into the intraluminal thrombus in abdominal aortic aneurysms is associated with rupture. J Vasc Surg 48(5): 1108-1113.

- Testa A, Lauritano EC, Giannuzzi R, Giulia Pignataro, Ivo Casagranda, et al. (2010) The role of emergency ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute non-traumatic epigastric pain. Intern Emerg Med 5(5): 401-409.

- Metcalfe D, Holt PJ, Thompson MM (2011) The management of abdominal aortic aneurysms. BMJ 342:

-

Chris R Darby, Katherine Hurst, Ashok Handa. ABCD…Airway, Breathing, Circulation (and don’t forget Differentials). Arch Clin Case Stud. 2(3): 2020. ACCS.MS.ID.000540.

-

Dialysis Access Steal Syndrome, Ischemic monomelic neuropathy, Limb Ischemia, AV access, Peripheral vascular disease, Paresthesia, Absent pulses, Cerebrovascular disease, Hypertension.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.