Case Report

Case Report

A Rare Case of Enoxaparin Induced Reversible Pancytopenia in a Patient of Decompensated Cryptogenic CLD with Portal Hypertension with Portal Vein Thrombosis Due to Protein S Deficiency

Richmond Ronald Gomes*1, Habiba Akhter2 and Sayeda Noureen 3

1Department of Medicine, Associate Professor, Ad-din Women’s Medical College & Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh

2Department of Medicine, Clinical Assistant, Ad-din Women’s Medical College Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh

3Medical Officer, Medicine, Ad-din Women’s Medical College Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Richmond Ronald Gomes, Department of Medicine, Addin Women’s Medical College & Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Received Date: August 11, 2020; Published Date:August 28, 2020

Abstract

Subcutaneous Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) enoxaparin, given at therapeutic dose of 1mg/kg twice daily, is as effective and safe as intravenous unfractionated heparin for treating acute venous thromboembolic disease. Heparin may cause drug induced immune thrombocytopenia which is caused by IgG anti- platelet factor-4 antibody and heparin immune complexes, resulting in platelet activation, clumping, and thrombotic events. It occurs <1% of patients in intensive care units but can occur in any patient on long-term heparin therapy. But heparin induced pancytopenia is a very rare event in clinical practice, here we present a case of 23 years old lady who presented to us with progressive abdominal distension and abdominal pain with the history of recent intrauterine death (IUD). Later she was diagnosed as a case of portal vein thrombosis due to protein S deficiency with decompensated chronic liver disease (CLD) with portal hypertension. She started treatment with therapeutic doses of subcutaneous enoxaparin. Eventually she developed pancytopenia. Upon discontinuation of enoxaparin and after ruling out other causes of pancytopenia, her pancytopenia reversed completely.

Keywords:Enoxaparin; Pancytopenia; Portal vein thrombosis; Chronic liver disease

Introduction

Venous thromboembolic diseases are a group of heterogeneous diseases with different clinical forms and prognosis [1]. The fundamental goal of pharmacological treatment and prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism is to avoid lethal pulmonary embolism that occurs in up to 5% of high-risk patients.

Low molecular weight heparins (LMWH) are widely used for treatment and prophylaxis of thromboembolic diseases when there are acquired and inherited thrombophilic conditions or when there is immobilization for more than one week [1-3]. Previous studies showed that heparin induced thrombocytopenia is an acquired disorder that effects about 3% of patients receiving unfractionated heparin and 0.6% of the patients receiving LMWH3. Reversible pancytopenia as a manifestation after LMWH administration is a very rare clinical situation.

Case Presentation

A 23 year old nonalcoholic, non-smoker lady (gravida 2), not known to have diabetes and hypertension with the history of recent IUD due to PIH (pregnancy induced hypertension) at 35+ weeks of gestation referred from department of gynecology and obstetrics presented to us with the complaints of progressive abdominal distention for 15 days and upper abdominal pain for 3 days. But she denied any history of yellow coloration of urine and sclera, shortness of breath, decrease in urinary output, altered sensorium involuntary movement, fever, joint pain, any pigmentation hematemesis or melena. Her bowel habit was normal. Apart from calcium and hematinic, she was free of any medications. There was neither personal nor family history of liver disease nor any venous thrombosis. She had no past history of jaundice or previous fetal loss or taking any oral contraceptives prior pregnancy. On examination, she was conscious, oriented. Mild pallor was present but there was no jaundice or cyanosis. There were no skin or nail changes including no spider angioma. Axillary hair was sparse. Mild pedal edema was present. Vitals were stable. Flapping tremor was absent. Abdominal examination revealed hugely distended abdomen with presence of abdominal striae and distended vein the flow of which suggests portal venous obstruction. Ascites was present as suggested by presence of fluid thrill. Organomegaly could not ascertained due to tense ascites. But there was tenderness over right hypochondriac region without any rebound tenderness. Other systemic examination revealed no abnormalities. Complete blood count showed mild normocytic normochromic anemia with hemoglobin 10.3 gm/dl(normal 12-16 gm/dl), MCV 81.4 fL (normal 78-98 fL), MCH 28.5 pg (normal 26-32 pg), total white cell count 7.61×103/uL (N-67.3%, L-18.9%), total platelet count 152×103/ uL( 150-450×103/uL).Serum bilirubin 1.1 mg/dl(normal 0.5-1.8 mg/dl) SGPT- 24 U/L(normal up to 31U/L), serum total protein 44.89g/L( normal 66-83 g/L), serum albumin 14.15 g/L(normal 35-52 g/L), serum globulin 30.74 g/L(normal 23-35 g/L), A: G 0.46:1(normal 1.1:1), serum creatinine 0.68 mg/dl(normal 0.5-1.3 mg/dl). Serum electrolyte showed sodium 139 mmol/L (normal 135-145 mmol/L), potassium 3.8 mmol/L (normal 3.5-5.5 mmol/L). ANA was negative (17.51 U/ml, normal < 20 U/ml). TSH was mildly raised 8.42 mIU/mL (normal 0.35-5.5mIU/mL).

Prothrombin time was normal with 1 second difference between patient and control with INR 0.96. D-dimer values were more than 200 micro gm/ml. Urine routine examination showed ++proteinuria with presence of 8%(non-significant) dysmorphic RBC with urinary total protein 1.96g/24 hours. Ascitic fluid study showed lymphocyte rich (total cell 350/cmm, L-99%) transudative ascites (protein 0.29 g/dl).

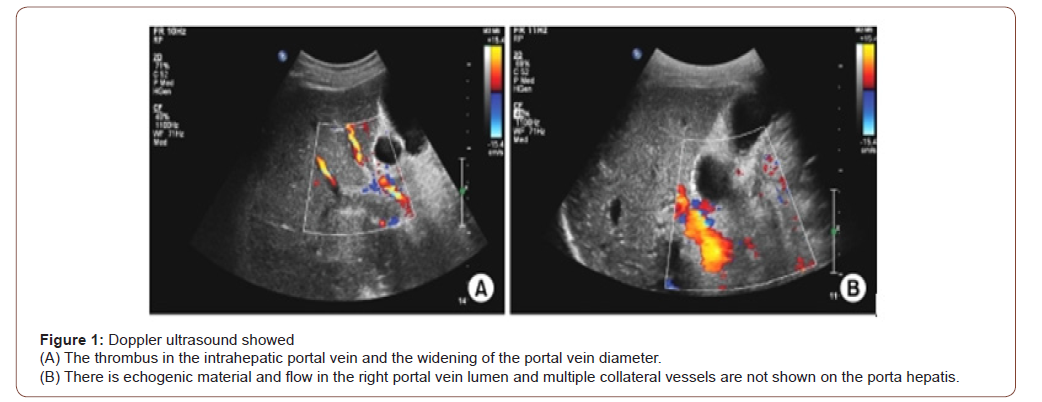

Ascitic fluid ADA was 2.55 U/L (normal <25 U/L). Doppler ultrasonography of whole abdomen revealed early chronic parenchymal change of liver with widened portal vein (15.4 mm) suggestive of portal vein thrombosis, splenomegaly with mildly dilated portal vein, postpartum grossly bulky uterus, huge ascites (Figure 1). Echocardiography failed to reveal any cardiac disease. HBsAg, Anti HBc (total), Anti HCV were negative. Urinary copper excretion was insignificant (12.30 mg/dl, normal 0-105 mg/dl)) Thrombophilia screen was performed, not including screening for JAK2V617F mutation, homocysteine level, prothrombin mutation, factor V Leiden mutation revealed which revealed negative lupus anticoagulant, anti-cardiolipin antibody. Anti-thrombin III (106%, normal 75-125%) and protein C (54%, normal 50-120%) were normal but protein S level was significantly reduced (34%, normal 50-120%). Endoscopy of upper GIT, liver biopsy and fibro scan of liver could not be done due to COVID situation. On the basis of clinical features and lab parameters she was diagnosed as a case of decompensated cryptogenic chronic liver disease with portal hypertension with portal vein thrombosis secondary to protein S deficiency.

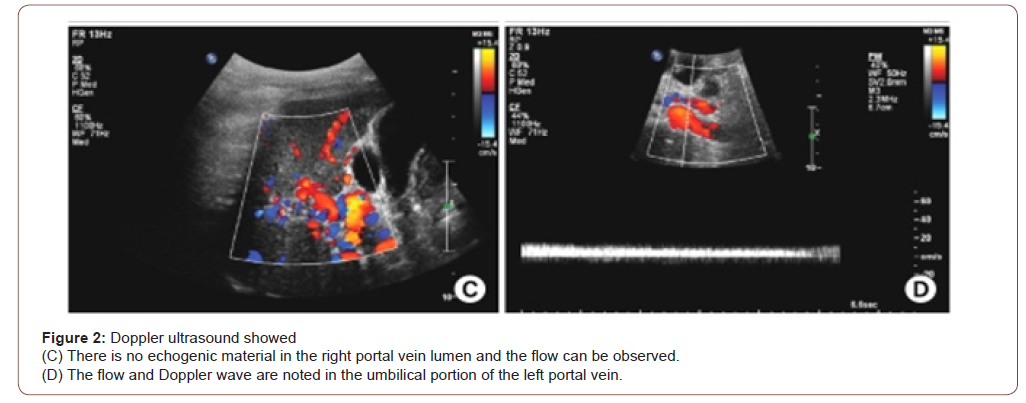

So, she was started treatment with large volume paracentesis with intravenous albumin support, diuretics, low dose thyroxin, nonselective beta blocker, and subcutaneous therapeutic doses of enoxaparin along with fluid and salt restriction. With treatment she started responding both clinically and biochemically. But on 3rd day of anticoagulation, repeat complete blood count revealed pancytopenia (anemia with hemoglobin 8.1 gm/dl(normal 12-16 gm/dl), MCV 86.7 fL (normal 78-98 fL), MCH 27.3 pg(normal 26- 32 pg), total white cell count 2.25×103/uL (N-71.6%, L-14.8%), total platelet count 70×103/uL(150-450×103/uL). Peripheral blood film showed pancytopenia with negative direct coomb’s test, Serum reticulocyte count was reduced 0.50% (normal 1.5%-2.5%). As there was a suspicion of enoxaparin induced pancytopenia, enoxaparin was substituted with tablet rivaroxaban. Daily monitoring of complete blood count was done which revealed progressive improvement of count in all cell lines. During discharge, 7th day after stopping enoxaparin, her complete blood count showed hemoglobin 8.4 gm/dl (normal 12-16 gm/dl), MCV 84.5 fL(normal 78-98 fL), MCH 26.5 pg(normal 26-32 pg), total white cell count 3.27×103/uL(N-54.8%, L-36.7%), total platelet count 145×103/ uL(150-450×103/uL). After 2 weeks during outpatient door follow up her complete blood count revealed almost normal count of all cell lines with hemoglobin 11.10 gm/dl(normal 12-16 gm/dl), MCV 85.1 fL (normal 78-98 fL), MCH 28.1 pg(normal 26-32 pg), total white cell count 6.10×103/uL (N-67%, L-26%), total platelet count 152×103/uL(150-450×103/uL). Rivaroxaban was continued for six months without any complications. Warfarin was not given as there was a concern both for bleeding and regular monitoring with INR. After 6 months repeat Doppler ultrasonography of abdomen showed complete recanalization of portal vein with improved flow with normal portal venous diameter (Figure 2). There was no ascites.

Discussion

Pancytopenia is a clinical condition characterized by decrease in count of all cell lines in peripheral blood that is anemia (hemoglobin less than 12-14 gm/dl taking in account age and sex of patient), leucopenia (white cell count less than 4500×109/L) and thrombocytopenia( total platelet count less than 150000×109/L) [4]. Depending on the degree of each cytopenia, pancytopenia is further catalogued into mild moderate or severe. There are few studies in literature that explores the various etiological factors of pancytopenia. In a recent study [5], in 45% patients with pancytopenia, a hypocellular bone marrow and aplastic anemia were found, the latter being the most common cause of pancytopenia in their set. Numerous drugs cause dose dependent or dose independent bone marrow toxicity thereby causing pancytopenia among which the most important drugs are linezolid [6] chloramphenicol, indomethacin, gold salts, anticonvulsants, antimalarials, antithyroid, clonazepam [7], allopurinol, ticlopidine. Also, there are numerous infections like infections caused by herpes virus family specially cytomegalovirus [8], tuberculosis or kala-azar can cause pancytopenia either by direct toxic effect on bone marrow stem cell or by inducing anomalous immune responses. Finally, the most common cause of secondary pancytopenia in clinical practice is peripheral sequestration by hypersplenism secondary to liver disease and inefficient erythropoiesis by vitamin B12 deficiency (megaloblastic anemia) [9,10].

The use of low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWHs) have become popular in the past 2 decades. Major advantages of them over unfractionated heparin are a lack of need of activated partial thromboplastin time monitoring and ease of application in an out of the hospital environment. Clinical trials revealed that LMWHs are at least as effective as unfractionated heparin and, yet, have fewer side effects in many disease conditions [11-15]. This is especially true for heparin induced thrombocytopenia, which is encountered much more commonly with unfractionated heparin use than with LMWH13. Enoxaparin, an LMWH used to treat and prevent deep venous thrombosis, has been evaluated in several clinical trials11-13. Physicians use it in a very wide spectrum of clinical conditions [14,15].

In our case, enoxaparin was discontinued after discarding all possible secondary etiologies in such a low resource setting and ruling out other common drugs that can cause pancytopenia as a probable side effect. In the literature only two case reports described similar development of pancytopenia after enoxaparin administration [10,16]. That reaffirms the importance of monitoring the patients receiving enoxaparin. The patient should be periodically checked for the development of more commonly known thrombocytopenia and rare possible pancytopenia. The discontinuation of enoxaparin with gradual improvement of count of all cell lines in pancytopenia suggests that the enoxaparin induced pancytopenia is reversible.

Conclusion

Although low molecular weight heparin has advantages over unfractionated heparin, clinicians must be wary of its potential complications, which may sometimes be life-threatening. The patient should be monitored with periodic analyses to check both the known thrombocytopenia as well as possible rare pancytopenia. The cessation of administration of enoxaparin usually results in gradual improvement of hematological parameters in pancytopenia. To our knowledge, only two previous case study reported pancytopenia as a side effects of enoxaparin.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflicts of Interest

No Conflicts of Interest.

References

- Lacut K, Le Gal G, Mottier D (2008) Primary prevention of venous thromboembolism in elderly medical patients. Clin Interv Aging 3(3): 399-411.

- Montero Ruiz E, Baldominos Utrilla G, Lopez Alvarez J, Santolaya Perrin R (2011) Effectiveness and safety of thromboprophylaxis with enoxaparin in medical inpatients. Thromb Res 128(5): 440-445.

- Laporte S, Liotier J, bertoletti L, Klebler FX, Pineo GF, et al. (2011) Individual patient data meta-analysis of enoxaparin vs unfractionated heparin for venous thromboembolism prevention in medical patients. J Thromb Haemost 9(3): 464-472.

- Tariq M, Khan N, Basri R, Amin S (2010) Aetiology of pancytopenia. Professional Med J 172: 252-256.

- Santra G, Das BK (2010) A cross-sectional study of clinical profile and aetiological spectrum of pancytopenia in a tertiary care center. Singapore Med J 51(10): 806-812.

- Green SL, Maddox JC, Huttenbach ED (2001) Linezolid and reversible myelosuppewssion. JAMA 285: 1291.

- Bautista Quach MA, Liao YM, Hseuh CT (2010) Pancytopenia associated with clonazepam. J Hematol Oncol 3: 24.

- Koukoulaki M, Infanti G, Grispou E, Papastamopoulos V, Chroni G, et al. (2010) Fulminant pancytopenia due to cytomegalovirus infection in an immunocompetent adult. Braz J Infect Dis 14(2): 180-182.

- Braza JM, Bhargava P (2008) A medical mystery: a 71 year old man with pancytopenia. N Engl J Med 359: 1941.

- Gayathri BN, Rao KS (2011) Pancytopenia: a clinic-hematological study. J Lab Physicians 3(1): 15-20.

- Merli G, Spiro TE, Olsson CG, U Abildgaard, BL Davidson, et al. (2001) Subcutaneous enoxaparin, given once or twice daily, is as effective and safe as intravenous unfractionated heparin for treating acute venous thromboembolic disease subcutaneous enoxaparin once or twice daily compared with intravenous unfractionated heparin for treatment of venous thromboembolic disease. Ann Intern Med 134(3): 191-202.

- Walenga JM, Jeske WP, Prechel MM, Peter Bacher, Mamdouh Bakhos (2004) Decreased prevalence of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia with low-molecular-weight heparin and related drugs. Semin Thromb Hemost supp 1: 69-80.

- Warkentin TE, Levine MN, Hirsh J, P Horsewood, RS Roberts, et al. (1995) Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in patients treated with low-molecular weight heparin or unfractionated heparin. N Engl J Med 332(20): 1330-1335.

- Hofmann T (2004) Clinical application of enoxaparin. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2(3): 321-337.

- Noble S, Peters DH, Goa KL (1995) Enoxaparin: a reappraisal of its pharmacology and clinical applications in the prevention and treatment of thromboembolic disease. Drugs 49(3): 388-410.

- Sari I, Davutoglu V (2007) Enoxaparin induced reversible pancytopenia. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 13(4): 453-454.

-

Richmond Ronald Gomes, Habiba Akhter, Sayeda Noureen. A Rare Case of Enoxaparin Induced Reversible Pancytopenia in a Patient of Decompensated Cryptogenic CLD with Portal Hypertension with Portal Vein Thrombosis Due to Protein S Deficiency. 2(4): 2020. ACCS. MS.ID.000545.

-

Nonstructural nuclear proteins, Lung cell membrane, Virus, Patients, Infection, Pandemic strain.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.