Research Article

Research Article

Perinatality and Childbirth as a Factor of Decompensation of Mental Illness: The Case of Depressive States in Newly Delivered Cameroonian Women

Georges Pius Kamsu Moyo*

Faculty of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University of Yaoundé I, Cameroon.

Georges Pius Kamsu Moyo, Faculty of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University of Yaoundé I, Yaoundé, Cameroon.

Received Date: July 27, 2020; Published Date: August 12, 2020

Abstract

Decompensation in psychiatry refers to the process by which a previously stable patient or predisposed individual may suddenly manifest symptoms or experience exacerbation of a sickness. This is prompted by factors which may be physiological, pathological, endogenous or exogenous, being responsible for psychic disequilibrium. Perinatality is characterized by multiple hormone variation and stress, which may constitute a risk for mental imbalances. The baby blues is a precocious and transient depressive state of the postpartum, which may occur as a borderline, signalling psychic decompensation. This study aims to investigate the phenomenon in women predisposed to mental disorders, having manifested the baby blues during immediate postpartum. In a case control study conducted in 2015 in two teaching hospitals of Yaoundé, Cameroon over four months, the Kennerley and Gath blues screening permitted to separate the group of “cases” from that of “controls”. After various analyses, women with psychological and psychiatric risk factors including: past history of depression (OR=6.8; p<0.001), past history of postpartum blues (OR=2.3; p=0.002), past history of other psychiatric illnesses (OR=10.21; p<0.01), family history of depression (OR=3.58; p<0.001), family history of other psychiatric illnesses (OR=4.39; p<0.001), current chronic diseases (OR=2.33, p-value<0.001), sickness or complication during pregnancy (OR=2.53, p-value<0.0211) were more susceptible to manifest the baby blues during immediate postpartum. Therefore, women with psychological predispositions, stand a risk of decompensation during the perinatal period including psychiatric disorders of postpartum. Preventive measures such as counselling, keen monitoring and treatment adjustment may help to prevent this phenomenon.

Keywords: Perinatality; Childbirth; Decompensation; Mental illness

Introduction

There exists an increased risk of psychological impairments during the perinatal period as close to one woman out of three in our context may develop postpartum psychic derangements [1]. In theory, this discomfort is partly attributed to the physiological hormone variations that occurs during pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding, which may associate with environmental and psychosocial factors occurring during the same period [2,3]. However, in reality, neonatal and other obstetrical factors than hormone variation may have a considerable influence as well [neonatal factors]. The baby blues may be defined as a mild, transient depressive state that occurs during the early postpartum period, within the first two weeks of the puerperium [2,3]. It may be considered as a transitional state towards more important mental disorders of the puerperium rather than a pathological condition per se [4]. Nevertheless, the description of an atypically severe baby blues has been made by a number of researchers and comprises characteristics or signs and symptoms that may correspond to various forms of psychiatric disorders of the postpartum period [5]. This may allow for a “reconsideration theory” of the baby blues as a trigger point from which the other psychic derangements of postpartum emerge [4,6]. The baby blues may thus reflect a mental decompensation process developing in some predisposed women during the perinatal period. This is to say all psychic derangements of the postpartum may develop from a “baby blues” of “relative severity” which may be common or atypical as from its onset [4,7,8].

Methodology

A case-control study was carried out on an overall sample of 321 newly delivered women, of which 107 had been diagnosed with the baby blues and were considered as the group of “cases”, while the other 214 women who did not manifest emotional instability were considered as the “control” group. The study was carried out in two teaching hospitals of Yaoundé, Cameroon: The Yaoundé Gynaeco- Obstetric and Paediatric Hospital, and the Yaoundé Central Hospital which are referral and University teaching hospitals in Cameroon. After approval of the research protocol by the ethical committee, women who delivered at 28 weeks or more of pregnancy were enrolled, after their consent was obtained. A pretested questionnaire was administered, and information retrieved from the patients’ files. Data collected included socio-demographic characteristics, newborns parameters and the Kennerley and Gath questionnaire. The Kennerley and Gath blues questionnaire is a validated selfrating scale consisting of 28 items concerning the emotional state of newly delivered women. The available answers are “yes” or “no” corresponding respectively to marks of 1 and 0 with a maximum possible score of 28 and a minimum of 0. The scale served as a diagnostic and explorative tool. Women who had an overall score greater than the mean peak score of their group were considered as positive for emotional instability.

The calculated minimal sample size was 41 cases for 82 controls based on the 31.3% prevalence of baby blues among Nigerian women in postpartum, reported by Adewuya and using Schlesselman’s formula with a standardized power of 84%. Statistical analyses were done using CSPro version 4.1 and SPSS version 22.0 software. The difference between variables assessed was statistically significant for P-value < 0.05. Pearson Chi square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare proportions. Odds Ratio (OR) and 95% Confidence interval (CI) were calculated to assess the association between variables and emotional instability. Multivariate analysis served for isolating independent predictive factors.

Result

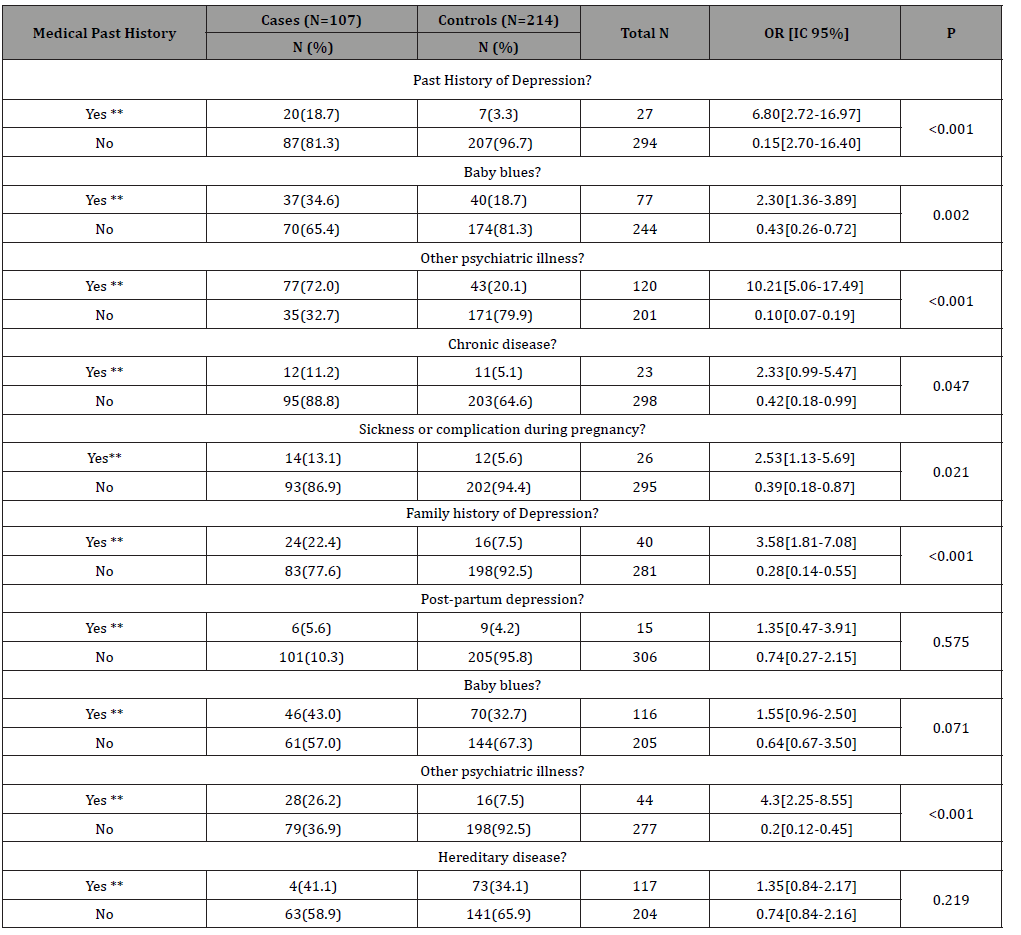

Psychiatric and psychological factors with statistically significant association with baby blues were patients with: past history of depression (OR=6.8; p<0.001), past history of postpartum blues (OR=2.3; p=0.002), past history of other psychiatric illnesses (OR=10.21; p<0.01), family history of depression (OR=3.58; p<0.001), family history of other psychiatric illnesses (OR=4.39; p<0.001), current chronic diseases (OR=2.33, p-value<0.001), sickness or complication during pregnancy (OR=2.53, p-value<0.0211) (Table 1).

After multivariate analysis by logistic regression, past history of depression persisted as an independent predictive factor (Table 2).

Table 1: Psychiatric and psychological factors in relationship with the baby blues.

Table 2: Possible independent predictive risk factors for maternity blues after caesarean section.

Discussion

As already described by Harris and stein in the 1980ies, past history of depressive states including major and milder states such as the baby blues, just as other psychiatric disorders, were all found as risk factors for developing the baby blues in this survey [9,10]. In effect, these factors may be discussed in terms of the “weakening effect” and hence the equilibrium disruption that they may produce on the mental state of an individual. The baby blues is generally considered as a “trivial” and “fleeting” transitional depressive state often described as a physiological impairment, rather than a true pathology on its own [4,5]. It may therefore occur in some newly delivered women as an indicator and a signal or a mode of decompensation of a terrain partially weakened by other psychiatric conditions and predispositions [11,12]. It could as such reveal the “psycholabile” nature of an individual. This phenomenon may be justified by the relationship existing between the baby blues and postpartum depression, in which the baby blues appears as a psychological impairment, being predictive for postpartum depression [4,10,13]. This “psychological weakening effect” through which a current situation such as childbirth exacerbates signs in some previously balanced individuals with regards to mental state, may be the reason why most researchers exclude women with psychiatric history in similar studies [11-14].

Family history of depression and other psychiatric illnesses equally appeared as risk factors for the onset of the baby blues in this survey. As a hypothetical explanation for these results, a hereditary or genetic predisposition influencing the manifestation of the baby blues by some women may be suggested. This would not be strange, as heredity has been strongly suspected in the genesis of some depressive conditions in psychiatry [15-18]. Perinatality and childbirth in such cases may therefore act as prompting events, facilitating the expression of latent or inexpressive genes.

Sickness and other complications occurring during pregnancy may constitute life-threatening emergencies requiring urgent intervention, given that the life of the mother or the foetus may be at stake. These factors appeared as predispositions to the baby blues and is consistent with similar relationships evoked by some other researchers under different terms indicating the same phenomenon [8,15-18]. In effect, these conditions occurring in the course of pregnancy and hence the perinatal period may be stressing factors generating anxiety in women and triggering mood disorders during the postnatal period [8,16,11].

Chronic diseases may lead to limitations and deterioration of life quality, resounding on the psychological state of an individual. Associations between depressive states, altered life quality and chronic disorders have been established by a number of researchers worldwide [15-18]. This may explain the manifestation of the baby blues as a mild depressive syndrome of the postpartum period, prompted by perinatality and delivery.

Conclusion

Women with pre-existing psychological or psychiatric conditions, or family predispositions stand a risk of decompensation during the perinatal period including acute psychic manifestations during the postpartum period. Preventive measures such as counselling, keen monitoring and treatment adjustment may help to prevent this phenomenon.

Authors contributions

The authors participated in all steps of the study.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Acknowledgment

Hospitals authorities, all collaborators to this project

Conflicts of Interest

No conflicts of interest.

References

- Oates M (1987) Major mental illness in pregnancy and puerperium. Baillieres Clin Obstet Gynaecol 3(4): 905-920.

- Rezaie Keikhaie K, Arbabshastan ME, Rafiemanesh H, Amirshahi M, Mogharabi S, et al. (2020) Prevalence of the Maternity Blues in the Postpartum Period. J Obstet Gynecol Neoatal Nurs 49(2): 127-136.

- Virginie IM, Michel riex (2019) Baby blues. Eres spirale 89: 131-135.

- Georges Pius Kamsu Moyo, Nadege Djoda (2020) Relationship Between the Baby Blues and Postpartum Depression: A Study Among Cameroonian Women. American Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. 8(1): 26-29.

- Kennerley H, Gath D (1994) Maternity blues. Br J Psychiatry. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins 155: 367-373.

- O Hara MW, Schlechte JA, Lewis DA, Varner MW (1991) Controlled prospective study of post-partum mood disorders: Psychological, environmental and hormonal variables. J Abnorm Psychol 100(1): 63-73.

- Lemperiere T, Rouillon F, Lepine JP (1984) Psychic disorders linked to the puerperium. Medico-surgical encyclopedia Psychiatry 7.

- Savage GE (1975) Observation on the insanity of pregnancy and childbirth. Guy’s Hospital Rep 20: 83.

- Harris B (1980) Maternity blues. Br J Psychiatry 136: 520-521

- Stein GH (1980) The pattern of mental change and body weight change in first postpartum week. J Psychosom Res 24: 165-171.

- F Gonidakis, AD Rabavila, E Varsou, G Kreatsas, G N Christodoulou (2007) Maternity blues in Athens. J Affect Disord 99(1-3): 107-115.

- K Mbailara, J Swendsen, E Glatigny Dallay, D Dallay, D Roux, et al. (2005) The baby blues: clinical characterization and influence of psycho-social variables. The enthalal 3(3): 331-336.

- Y Takahashi, K Tamakoshi (2014) Factors associated with early postpartum maternity blues and depression tendencies among Japanese mothers with full –term healthy infants. Nogo J Med Sci 76(1-2): 129-138.

- Alexandre FC, Paolo RM, Jose Julio A Tedesco, Soubhi Kahalle, Marcelo Zugaib (2008) Maternity blues: Prevalence and risk factors. Sp J Psychol 2(11): 593-599.

- Bremmer M A et al. (2006) Depression in older age is a risk factor for ischemic cardiac events. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 14(6): 523-530.

- ASE Akabawi, Witte JG Hoogendijk, Dorly JH Deeg, Robert A Schoevers, Bianca WM Schalk, et al. (1988) The nature and associates of maternity blues in an Egyptian culture. Egypt J Psychiat 11:57-80.

- Katon WJ (2011) Epidemiology and treatment of depression in patients with chronic medical illness. Dialogue Clin Neurosci 13(1): 7-23.

- Moussavi S, Somnath Chatterji, Emese Verdes, Ajay Tandon, Vikram Patel, et al. (2007) Depression chronic diseases and decrement in health: results from the World Health Survey. Lancet 370(9590): 851-858.

-

Georges Pius Kamsu Moyo. Perinatality and Childbirth as a Factor of Decompensation of Mental Illness: The Case of Depressive States in Newly Delivered Cameroonian Women. 4(4): 2020. ABEB.MS.ID.000592.

-

Perinatality, Childbirth, Decompensation, Mental illness, Neonatal factors, Physiological hormone, Pregnancy, Childbirth, Breastfeeding

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.