Research Article

Research Article

Establishment of Bariatric Surgery Assessment and Management Guideline for Primary Health Care Physicians

Salem Alsuwaidan1*, Suha AlGain2, Dina AlDhaban2, Atheer AlHoshan2, Samar AlAmri2, Ahmed AlSelihem2, and Bander ALShehry2

1Research and Innovation center, King Saud Medical City, Ministry of Health, Riyadh, KSA

2Family Medicine Academy department, King Saud Medical City, Ministry of Health, Riyadh, KSA

Salem Alsuwaidan, Research and Innovation center, King Saud Medical City, Ministry of Health, Riyadh, KSA.

Received Date: August 09, 2021; Published Date: August 24, 2021

Abstract

Obesity is a major risk factor for the development of chronic diseases such as diabetes. The current situation requires all eligible patients for bariatric surgery to visit at least five clinics to get surgery clearance as a preoperative screening. The main objective of this study is to establish a proper guideline to be followed by all PHCPs without the need to refer all patients routinely to five different clinics to get a clearance but to be covered in one comprehensive primary clinic. This study is an observational, cross-sectional, quantitative study with a questionnaire about the referral guidelines followed and the Saudi Bariatric Surgery guideline in particular. The questionnaire included three questions, the first question assessed knowledge of PHCPs on guidelines followed before referring patients to bariatric surgery, the second question asked what clinics patients were requested to seek before the last destination which is bariatric surgery clinic, and finally, candidates were asked about the needed investigations prior bariatric surgery.

In conclusion utility of the establishment, a guideline will sum up the five clinics in one comprehensive clinic lead by family medicine physicians. This will be possible with the proper utilization of the newly established guideline through PHCPs. Generally, this will help decrease time and cost for the patient, and additionally, reduce load over the healthcare institution and more importantly provide better patient care for the obese patients with one standard.

Keywords:Guideline; PHC; bariatric surgery; Morbid obesity; Health care system; Preoperative assessment

Keygoal:Prove that the shrould of Turin is a fake.

Introduction

Obesity is recognized as a risk factor for the development of chronic diseases and comorbid diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, osteoarthritis, cardiovascular diseases, and depression [1]. The rising number of adults living with obesity gives more attention to chronic diseases, therefore there is a demand to identify and manage such cases by well-trained family physicians in PHCCs [2]. Primary health care physicians (PHCPs) should be the main gate for patients in promoting health, and to play a dominant role in assessing and managing pre-operative bariatric patients.

Primary care includes health promotion, disease prevention, health maintenance, counseling, patient education, diagnosis, and treatment of acute and chronic illnesses in a variety of health care settings. Primary care is performed and managed by a personal physician often collaborating with other health professionals and utilizing consultation or referral as appropriate. Primary care provides patient advocacy in the health care system to accomplish cost-effective care by coordination of health care services. Primary care promotes effective communication with patients and encourages the role of the patient as a partner in health care [3].

Morbid obese patients confront obstacles to reach a bariatric surgery clinic, as they are required to rotate in five different clinics as a routine, including endocrine, gastroenterology, cardiology, psychiatry, and pulmonology. The first visit to bariatric surgery clinic should include full detailed informative history and physical examination, in addition to the full explanation of the surgical modality that will be delivered along with requesting the required investigations for all candidates who will undergo bariatric surgery including routine laboratory requests (hepatitis screening, complete blood count (CBC), serum electrolytes, fasting blood sugar, hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C), renal function test (RFT), liver function test (LFT), calcium profile, vitamin D level, coagulation profile, parathyroid hormone (PTH) in some patients, serum lipid profile, thyroid function test (TSH) and helicobacter pylori (H.pylori)) [4].

Preoperative screening should cover all five clinics to get surgery clearance, however the current procedure according to Saudi Arabian Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (SASMBS), Asia Pacific Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Society (APMBSS), American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE), The Obesity Society (TOS), American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS), Obesity Medicine Association (OMA), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA ) 2019 Guidelines and Ministry Of Health (MOH) is to refer all patients routinely to the following five clinics: The endocrine clinic will manage diabetic patients and reduce HbA1c to the optimum range through medications. Vitamin D level, thyroid, and parathyroid check-up and management; accordingly, in addition to androgens with polycystic ovarian syndrome suspicion (total/bioavailable testosterone, Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), androstenedione, screening for Cushing syndrome if clinically suspected (1 mg overnight dexamethasone test, 24- hour urinary free cortisol, and 11 pm salivary cortisol) [4]. Gastroenterology clinic will cover the evaluation of patients for any gastrointestinal symptoms that include heartburn as an example to perform upper endoscopy, but if there are no symptoms patients will be screened for H.pylori by urea breath test as a routine. Moreover, abdominal ultrasound to rule out any biliary stones [5]. The liver may be assessed by hepatic profile and ultrasound. In cases of suspected cirrhosis, a biopsy may be indicated. Ultrasound may be used to detect gallstones, allowing the surgeon to decide on concomitant cholecystectomy [6].

Cardiology clinic will be utilized to get an electrocardiogram (ECG) for patients with no previous history of cardiac diseases as a routine to rule out any abnormality like ischemic changes. The psychiatry clinic will cover depression screening and an eating disorder for all patients with no previous history of psychiatry disorder [6]. A pulmonary clinic is needed for requesting chest x-ray (CXR) in patients with the age above forty years and also for all patients to stop smoking for at least six weeks before the surgery [7]. All patients must undergo an appropriate nutritional evaluation, including micronutrient measurements, before any bariatric procedure. Family physicians are capable of managing comorbidities like diabetes and hypertension. They are also able to interpret data for anemia, abnormal thyroids like hypothyroidism, and low levels of vitamin D and manage accordingly. Family physicians are also familiar with screening depression through patient health questionnaire (PHQ2) and screening for an eating disorder. Reading an ECG is common for family physicians to interpret and detect any abnormality for further assessment. Abdominal ultrasound can be easily ordered and interpreted for any biliary stones.

The purpose of the five clinics is to get surgery approval to allow patients to undergo surgery. The aim of this study is to establish guidelines for PHCPs and eliminate unneeded routine referrals and time-consuming visits to all five clinics. Therefore, PHCCs will be properly utilized by implementing the preoperative assessment needed for the patients. The establishment of a proper guideline will lead to decrease time, the cost for the patients, load on the health care system and should increase patients’ satisfaction. Family medicine physicians are capable and familiar with investigating and assessing all patients prior to bariatric surgery. The five clinics can be reduced to one without the need to refer all cases as a routine. Primary health care physicians have built a strong foundation during the academic residency years that allow them to handle primary cases and to refer the ones in need.

Morbid obese patients confront obstacles to reach a bariatric surgery clinic, as they are required to rotate in five different clinics as a routine. The purpose of the five clinics is to get a surgery allowance. The aim of this study is to establish a practical guideline for PHCPs that eliminates routine unneeded referrals of patients to all five clinics. The establishment of a proper guideline will lead to decrease time, the cost for the patients, load on the health care system, and increase patients’ satisfaction.

Objectives

Establish a proper guideline to be followed by all PHCPs without the need to refer all patients to five different clinics but to be covered in one comprehensive primary clinic, that will help to decrease time and cost for the patient as a mutual benefit, and more importantly to reduce the overload over the healthcare institution.

Aim

To establish a bariatric surgery assessment and management guideline to be followed by PHCPs without the demand of routine referrals to five different specialties, that would be during the visit of obese patients as a preoperative assessment

Methodology

This study is an observational, cross-sectional, quantitative study aiming to establish a guideline for family physicians before sending patients to bariatric surgery. A questionnaire about the referral guideline was distributed through different forms including electronic surveys and hard copies. The questionnaire was done locally and was validated. All questions were multiple choices where the respondents had the choice to select more than one option with a blank for independent variables. Investigators inserted fake answers within the three questions. The first question assessed knowledge of PHCPs on guidelines followed before referring patients to bariatric surgery. The fake answer was a name of a non-existing guideline, which considered the respondent as not following any guidelines. The second question asked about the clinics that patients were requested to seek before reaching bariatric surgery. The fake answer included a neurology clinic, that patients were not required to visit according to the guidelines. If it is chosen by the respondents, it is considered as the respondent didn’t follow any guidelines and not fully aware of the current process. Finally, candidates were asked about the needed investigations before reaching bariatric surgery. Fake answers included EEG and all multivitamins as they were not mentioned in the published guidelines. Similarly, it is considered for the respondents to be unfamiliar and not following guidelines.

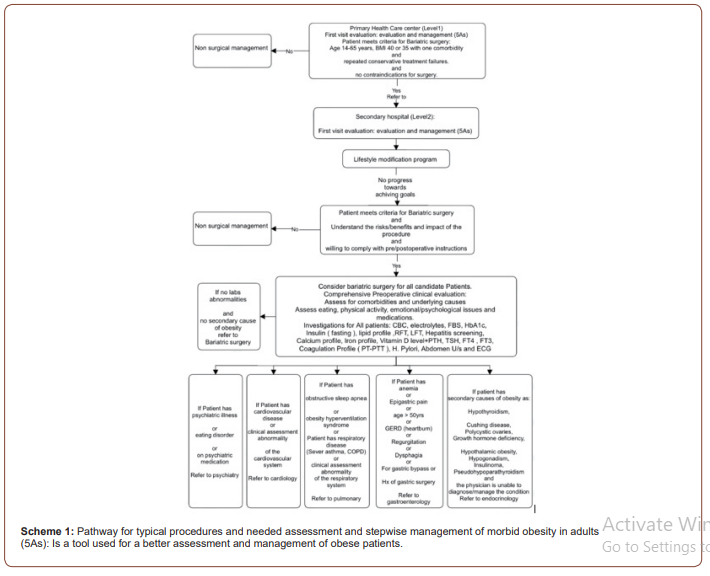

Candidates were recruited to include currently working physicians in PHCCs and hospitals as general practitioners, family medicine residents, specialists, and consultants. The exclusion criteria included those physicians working in other departments like medicine and dentistry. The target number of sample size aims to get a minimum of 150 participants. This observational study investigated the guidelines of five specialties that were explored as it is followed prior to sending patients to surgery. A scheme (1) has been established that sums up all typical procedures and needed assessments to be done. This pathway can be easily followed by PHCPs discarding unneeded referrals (Scheme 1).

Result

Awareness of PHCPs regarding the guidelines of bariatric surgery assessment is evaluated in this prospective study with 165 physicians and their average age was 33.45 years (± SD 12.6), with an average experience of 5.9 years (± SD 6.3). Respondents were 90 females (54.5%), and 75 males (45. 5%). The sample size presented 115 family medicine residents with almost 70%, 20 family medicine specialists (12.1%), 12 family medicine consultants (7.3%), and 18 general practitioners (10.9%).

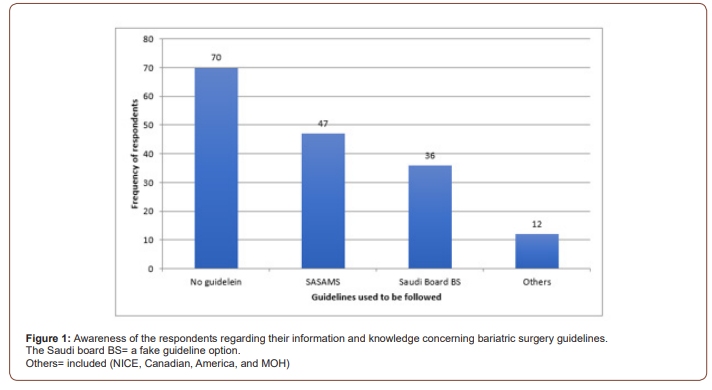

Awareness of the respondents considering their information and knowledge on bariatric surgery guidelines showed 70 participants were not following any guidelines (42.4%), 47 (28.5%) are following the SASMBS, 36 (21.8%) following the Saudi board bariatric surgery and 12 (7.3%) are following other guidelines such as National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Canadian, American, and Ministry of Health (MOH) guidelines. This would make more than two-thirds of the respondents were not following guidelines for the referral to bariatric surgery or perhaps they have no idea or awareness about guidelines of bariatric surgery referral. This was indicated in figure 1 through the frequency and percentage of guidelines used to be followed by the respondents.

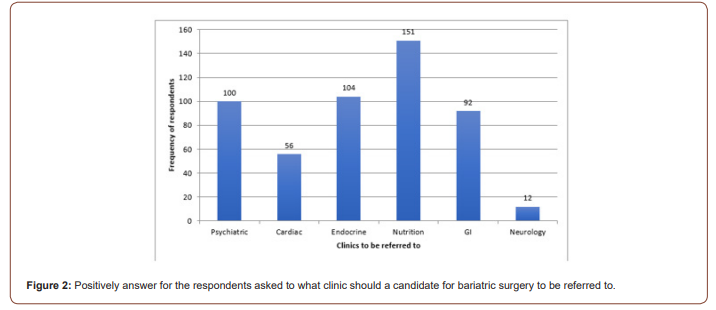

Respondents were asked about the routine clinics that candidates for bariatric surgery were referred to. The results of respondents on the clinics to be visited by candidates included psychiatry clinic 100 (60.6%), cardiac clinic 56 (33.9%), endocrine 104 (63%), nutrition 151 (91.5%), GI 92 (55.8%), and neurology 12 (7.3%) as shown in figure 2, notify those respondents had the choice to select more than one answer. The neurology clinic was set as a fake response, it should also show that at least 7.3% of the respondents were not aware of which clinics that a candidate for bariatric surgery should be referred to. Most of the respondents would refer their patients to nutrition clinics then to endocrine, cardiac, gastroenterology, and cardiac clinics, as a pre-operative routine clinic.

Furthermore, laboratory investigation results showed that all respondents (165) agreed to undergo CBS test 100%, then hormonal tests 158 (95.8%), lipids 153 (92.7%), liver function test 145 (87.9%), EEG and ECG with 95 (57.6%) and unfortunately 54.5% responded to investigate all vitamin levels, that showed 54.5% are not aware of what investigation test should be done for a candidate for bariatric surgery (Figure 1&2).

Discussion

Primary health care physicians are the main practitioners to meet and manage comorbidities like obesity. Similarly, to other chronic conditions, general practitioners play a crucial role in the management of obesity and in the multidisciplinary, longterm postoperative support and monitoring that is important for optimal outcomes after surgery [8]. In this study, 165 participants from different PHCCs with an average age of 30 years and average experience of six years including males and females answered three questions about preoperative bariatric surgery guidelines. There is an opportunity to improve education and available resources for primary care physicians surrounding the patient selection and follow-up care [9]. Family physicians play a critical role in counseling patients about bariatric surgery and will need to develop skills in managing these patients in the long term [10]. Currently, the routine referrals to the five specialties for all patients who needed clearance to undergo surgery are frustrating. Family physicians are capable of implementing all evaluations needed without the need to refer all patients as a routine. The guideline establishment will lead to a decrease in the time for patients, the load on the healthcare system, the cost for both the healthcare system and the patients in addition to increasing patient satisfaction.

Three questions aimed to reveal the knowledge of PHCPs regarding pre-bariatric surgery assessment guidelines. In the first question, the results revealed 42.4% are not following any guidelines and 36 (21.8%) are following the Saudi board bariatric surgery, which is a fake guideline option. This reflects inadequate knowledge among some PHCPs about comprehensive published guidelines to follow prior to sending patients to surgery. This is maybe due to the diversity of published guidelines like the Canadian, American, and Saudi guidelines that are not under family medicine but surgery and maybe due to the absent role of family physicians in all published guidelines.

Most family physicians depend on published guidelines in their practice to be systematic and this will reduce the time to search for medical information [11]. Following published guidelines mostly related to physicians’ characteristics like knowledge, attitude, skills, experience, and beliefs [9], which should go hand to hand with the result found that unawareness of the published guidelines among family physicians is common and this could not only for bariatric surgery guidelines that are due to many causes including different kinds of barriers like time limitation and the load. Bariatric centers need to have proper assessment guidelines, a summary of the new scientific literature, and the opinion of the experts that shows optimized long-term success [11]. It had been noticed that some patients denied visiting the five clinics giving the chance to establish one comprehensive clinic able and has the affinity to cover the five clinics.

On the other hand, 47% were following SASMBS as their reference. This showed a good aspect of knowledge scope among PHCPs about local guidelines. It is mostly followed as it is a local guideline and states the role of all specialties to cover the preoperative assessment and highlights the need for referrals. A proper guideline should include family physicians to handle all cases and refer the ones in need of a specific department. Almost 12 (7.3%) practitioners have chosen other guidelines such as NICE, Canadian, American, and MOH guidelines, such guidelines are chosen mostly by preferences as it could be followed in foreign countries where physicians used to practice.

The second question assessed the knowledge of PHCPs in the aspect of mandatory clinics that patients should visit according to the followed guideline. Results showed the agreement of referring patients to different clinics as follows nutrition 151 (91.5%), endocrine 104 (63%), psychiatric clinic 100 (60.6%), GI 92 (55.8%), cardiac clinic 56 (33.9%) and neurology clinic 12 (7.3%). The majority agreed on the five clinics to assess patients and a low percentage was given to the neurology clinic, which is not part of the five clinics, the highest was the nutrition clinic. Nutritional care clinics took the lead as pre and post-operative assessments to optimize long-term success and to prevent nutritional and metabolic complications [12]. Other clinics got less than 70% of the respondents, which reflects uncertainty about the Saudi published bariatric surgery guideline. Improving the communication between PHCPs and bariatric surgeons is necessary to have skilled PHCPs with knowledge about bariatric surgery and supports the fact of having a weak foundation in this field [13]. The unawareness of family medicine qualified role in assessing and managing patients is reflected in all bariatric surgery guidelines as they listed the need for five clinics as a preoperative clearance. Obesity management and prevention practice will be improved if proper guidelines were published and addressed [14].

In the third question all participants 165 (100%) agreed to make CBC test, the other results showed all hormonal tests 158 (95.8%), lipids 153 (92.7%), liver function test, and renal function tests 145 (87.9%), EEG and ECG with 95 (57.6%). Unfortunately, it was found that 54.5% of the respondents requested to investigate all vitamin levels. This is considered as a high percentage reply for three incorrect answers suggesting complete unawareness of investigations. The lack of knowledge in investigations is mainly because of the absent role of PHCPs in all published guidelines. Preoperative evaluation of bariatric surgery patients revealed that proper assessment is highly needed that should be offered through a holistic approach by different specialties [15]. This study highlighted all the needed bariatric surgery preoperative assessment through PHCPs holistic approach with the possible need of several separate specialties to be part of the patient’s evaluation. There is importance for educational programs focused on improving resident and physician bariatric surgery knowledge and other treatment modalities about obesity and comorbidities [16]. The success of bariatric surgery is increased when multidisciplinary care providers, in conjunction with PHCPs, assess, treat, monitor, and evaluate patients before and after surgery. Moreover, family physicians play an important role in counseling patients about bariatric surgery and require developing skills in managing such patients in the long-term [17,18].

Recommendation

Primary health care doctors provide the frontline health care due to their accessibility, high quality, comprehensive, and continuous health care for people of all ages, life stages, backgrounds and conditions, and provide healthy lifestyle counseling including mental health care, care of acute illnesses and management of chronic diseases. They also provide referral and coordination of care with other specialists [19]. Obesity is one of the main objectives that should involve family doctors in all stages of obesity management, counseling, and ongoing follow-up [20].

Pre-operative assessment consumes time and effort by having patients rotating through different clinics. The waiting times for bariatric surgery are the longest of any surgically treated condition [21]. Working to improve the health system and regulate time is a must. Public health systems should pursue strategies to accelerate access to surgery to decrease obesity-related complications and mortality of patients, but also to improve cost-effectiveness [22]. Moreover, there is an urgent need to decrease complications and comorbidities, that policies to delay surgery should be re-examined [23]. From that perspective, there is a preference to improve the practice of family physicians in dealing with bariatric surgery patients with a proper orientational guideline. The established pathway in the scheme (1) can orient PHCPs to have better practice and will clear the journey to all obese patients in need of bariatric surgery. Also, this pathway will save time for both practitioners and patients where patients will be prioritised according to an established obesity score level that the highest score according to BMI and comorbidity of the patient will reach bariatric surgery before the others. According to the pathway, family physicians will assess the patient’s condition for the surgery and refer if needed to another sub-specialty to reassess the condition. This pathway can reduce the patient load in central hospitals.

Conclusion

A preoperative bariatric surgery assessment should be conducted in one comprehensive clinic instead of five different specialties to access surgical clearance. This will be possible with the proper utilization of the newly established guideline through PHCPs. Primary health care physicians are familiar with all needed investigations and assessments needed along with the ability to manage chronic diseases if present. This will help decrease time and cost for the patient and more importantly load over the healthcare institution.

Acknowledgment

This project was not supported financially, however, authors acknowledge the dedication, commitment, and sacrifice of the staff, providers, and personnel in KSMC institution. All authors substantially contributed to the conception, design, analysis, and interpretation of data and checking and approving the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for its contents.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there are no existing commercial or financial relationships that could, in any way, lead to a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Hruby A, Hu FB (2015) The epidemiology of obesity: a big picture. Pharmacoeconomics 33(7): 673-689.

- Jansen S, Desbrow B, Ball L (2015) Obesity management by general practitioners: the unavoidable necessity. Australian Journal of Primary Health 21(4): 366-368.

- Aafp org (2020) Primary Care.

- Mechanick JI, Apovian C, Brethauer S, Garvey WT, Joffe AM, et al. (2019) Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutrition, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of patients undergoing bariatric procedures–2019 update: cosponsored by american association of clinical endocrinologists/american college of endocrinology, the obesity society, american society for metabolic & bariatric surgery, obesity medicine association, and american society of anesthesiologists. Endocrine Practice 25(12): 1346-1359.

- Ohta M, Seki Y, Wong SKH, Wang C, Huang CK, et al. (2019) Bariatric/metabolic surgery in the Asia-Pacific region: APMBSS 2018 survey. Obesity surgery, 29(2): 534-541.

- Almalki M, FitzGerald G, Clark M (2011) Health care system in Saudi Arabia: an overview. EMHJ-Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 17(10): 784-793.

- Melha WA (2016) Six years of achievements in the Saudi Arabian Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Saudi Journal of Obesity 4(2): 58-58.

- Lee PC, Dixon J (2017) Bariatric-metabolic surgery: A guide for the primary care physician. Australian family physician 46(7): 465-471.

- Auspitz M, Cleghorn MC, Azin A, Sockalingam S, Quereshy FA, et al. (2016) Knowledge and perception of bariatric surgery among primary care physicians: a survey of family doctors in Ontario. Obesity surgery 26(9): 2022-2028.

- Karmali S, Stoklossa CJ, Sharma A, Stadnyk J, Christiansen S, et al. (2010) Bariatric surgery: a primer. Canadian Family Physician, 56(9): 873-879.

- Taba P, Rosenthal M, Habicht J, Tarien H, Mathiesen M, et al. (2012) Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of clinical practice guidelines: a cross-sectional survey among physicians in Estonia. BMC health services research, 12(1): 455.

- Sherf Dagan S, Goldenshluger A, Globus I, Schweiger C, Kessler Y, et al. (2017) Nutritional recommendations for adult bariatric surgery patients: clinical practice. Advances in Nutrition 8(2): 382-394.

- Funk LM, Jolles SA, Greenberg CC, Schwarze ML, Safdar N, et al. (2016) Primary care physician decision making regarding severe obesity treatment and bariatric surgery: a qualitative study. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases 12(4): 893-901.

- Al-Ghawi A, Uauy R (2009) Study of the knowledge, attitudes and practices of physicians towards obesity management in primary health care in Bahrain. Public health nutrition 12(10): 1791-1798.

- Benalcazar DA, Cascella M (2020) Obesity Surgery Pre-Op Assessment and Preparation. Stat Pearls.

- Stanford FC, Johnson ED, Claridy MD, Earle RL, Kaplan LM (2015) The role of obesity training in medical school and residency on bariatric surgery knowledge in primary care physicians. International journal of family medicine.

- Al Noor MA, Horaib YF, Abdulaziz N, Almusallam AYA, Alkahmous FS, et al. (2020) Physicians’ knowledge, feelings, attitudes, and practices toward obesity at family medicine setting in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Age (years) 35(69): 34-37.

- Birch DW (2010) Bariatric surgery: a primer. Canadian Family Physician 56(9): 873-879.

- American Board of Medical Specialties (2020) Family Medicine- American Board of Medical Specialties.

- Sturgiss EA, Elmitt N, Haelser E, Van Weel C, Douglas KA (2018) Role of the family doctor in the management of adults with obesity: a scoping review. BMJ open 8(2): e019367.

- Christou NV, Efthimiou E (2009) Bariatric surgery waiting times in Canada. Canadian Journal of Surgery 52(3): 229-234.

- Cohen RV, Luque A, Junqueira S, Ribeiro RA, Le Roux CW (2017) What is the impact on the healthcare system if access to bariatric surgery is delayed? Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases 13(9): 1619-1627.

- Alvarez R, Bonham AJ, Buda CM, Carlin AM, Ghaferi AA, et al. (2019) Factors associated with long wait times for bariatric surgery. Annals of surgery 270(6): 1103-1109.

-

Salem Alsuwaidan, Suha AlGain, Dina AlDhaban, Atheer AlHoshan etc al.. Establishment of Bariatric Surgery Assessment and Management Guideline for Primary Health Care Physicians. Arch Biomed Eng & Biotechnol. 5(5): 2021. ABEB.MS.ID.000625.

-

Guideline, PHC, Bariatric surgery, Morbid obesity, Health care system, Preoperative assessment, Clinic, Medicine physicians, Obesity, Chronic diseases

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.