Review Article

Review Article

Back to Hippocrates? Information-Based Approach to Subjects’ Qualities, their Statistical Estimations, and Evolution

Independent Researchers, Moscow, Russia

Received Date: November 25, 2019 Published Date: December 06, 2019

Abstract

In the framework of the systemic-informational approach, a typology of elements’ behavior was derived, one of its bases being “neural force.” Every element (subject) can be ascribed either to ‘weak’ or ‘strong’ type (or certain intermediate degree). To measure this feature in application to creativity, two sources of empirical data were used, first dealing with 22-parametric description of 40 outstanding painters (of the 15th – 20th centuries), the second with 10 most important parameters of 200 ones. Both sets of primary data were based on calibrated expert estimations (up to 18 art historians). Several methods of information processing resulted in the ‘index of neural force’ of each painter, this index being capable of practical application in cultural studies, as well as in psychological and sociological investigations.

Keywords: Psychology; Systemic-information approach; Statistics; Neural typology; Painting creativity; Expert estimations; Principal component analysis; Indices

Introduction

About three decades ago, appeared a new vision of the features describing the behavior of any biological object, this universal vision being based on the information theory. (We mean the so-called systemic-informational approach – see, e.g., Golitsyn & Petrov, 1995.) In the framework of this approach, a set of parameters was deduced, proceeding from the very survival of the species (see Petrov, 2019). Among these features we find the so-called subject’s ‘neural force’ characterizing his/her maximal value of the resource mobilization, meaning both the force of nervous processes and usual physical force (see also Golitsyn, 1997, 2013). The heart of the matter consists in that the change of environmental conditions may cause quite different reactions: for ‘strong’ subjects the increasing of the environmental entropy causes the growth of activity and its effectiveness, whereas ‘weak’ subjects show decreasing diversity of activity and its diminishing effectiveness. Such a typology known from the times of Hippocrates, now experiences the ‘second breathing’ due to achievements of the systemic-informational approach. Each subject (or in general, each element of the system) can be ascribed to one of these two poles – or to a certain intermediate degree between them – with various behavioral consequences, both psychological and social. This parameter is universal, and hence, it can be investigated using various kinds of elements’ behavior, including those ones which seem to be rarely met, or even ‘exotic.’ Thus, “in artistic creativity, the difference between ‘weak’ type and ‘strong’ one is nothing else than the distinction between artistic temperaments. Weak type is characterized by low diversity of reactions: laconic, restrained features, stingy expressive means, inclination to small forms, attention to details, preference for nuances, ‘transparence’ of artistic language, and so forth. On the contrary, strong type is marked with violent colors, wealth of expressive means, preference for contrasts, ‘dense ecriture,’ inclination to large forms. <…> Of course, this difference in temperaments is inherent also to recipients, and it determines their reactions to works of art. Thus, for a recipient of a ‘strong’ type, creativity of an artist of ‘weak’ type, may cause the state of monotony, i.e., it seems to be too curt, dull, and languor. On the contrary, a recipient of ‘weak’ type reacts on works of a ‘strong’ artist by the state of the strain, irritation, impression of being too sham, rough, devoid of taste” (Golitsyn, 2013, p. 49) [1].

Previously we studied the indicators of this phenomenon in such specific field of behavior as musical creativity (Mazhul, Petrov, & Mazhul, 2016). Now we can compare these results – with analogous results concerning creative activity in the sphere of painting. Such comparison will hopefully come to some conclusions which would be capable of shading light onto the entire evolution of various systems.

Features of artistic creativity and their principal component analysis

At our disposal there were two sets of empirical data, both being ‘by-products’ of a large-scale investigation focused on hemispheric aspect of artistic creativity (Petrov & Boyadzhiyeva, 1996; Petrov & Mazhul, 2019). Both sources proceeded from calibrated expert estimations (from 8 to 18 experts for each painter), aimed at measuring the degree of left- or right-hemispheric prevalence inherent in the creativity of painters, both West-European and Russian [2].

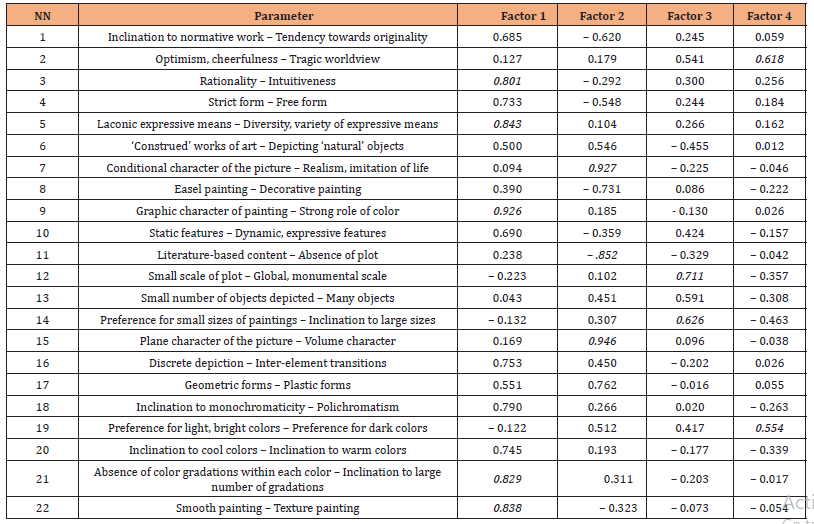

The first source dealt with 22 parameters, proposed by a group of experts (both psychologists and art historians). Each parameter had a form of a binary opposition (see Table 1), between two poles of which there were 6 gradations. After compiling this list of parameters, a list of hypothetical ‘contrastive’ eminent painters was also compiled. [This set contained names of 40 suggested ‘contrastive painters’: 20 belonging to left-hemispheric dominance and 20 to right-hemispheric one.] Then another group of experts (art historians) was involved, each of them being asked to put his/her estimate to the creativity of each painter. Then all the estimations obtained were processed by the procedure of principal component analysis (Petrov & Boyadzhiyeva, 1996). Some of its results are presented in Table 1: loads of each parameter onto the first four factors. [Loads possessing high values, are italicized: those which are more than 0.8 for first two factors, those exceeding 0.6 for the third factor, and exceeding 0.5 for the fourth factor.] [3] (Table 1).

Table 1: List of 22 parameters of painting and main results of principal component analysis – parameters’ loads onto four principal factors.

The four factors mentioned cover 35%, 27%, 12%, and 7% of the total dispersion, respectively. [Each of other factors covers dispersion less than unity, and they are not considered in the analysis.] The first factor responding to ‘hemispheric asymmetry,’ was examined in detail previously. The second factor was previously interpreted as ‘realistic character’ (Petrov & Boyadzhiyeva, 1996, pp. 128-131), the third one as the ‘factor of scale,’ and the fourth as the ‘factor of optimism [4].’

In general, interesting is the very grouping of parameters which form factors. It is important that the parameters possessing large loads onto one of the factors, reveal no substantial loads onto other factors. It means that each factor reflects its own, relatively autonomous aspect of creativity. However, there is no special factor responding to our ‘neural force’ in question. [Besides, in case of music the factor of ‘neural force’ appeared immediately as the second factor while application of the same procedure of ‘principal component analysis’ – see Mazhul, Petrov, & Mazhul, 2016. [5]

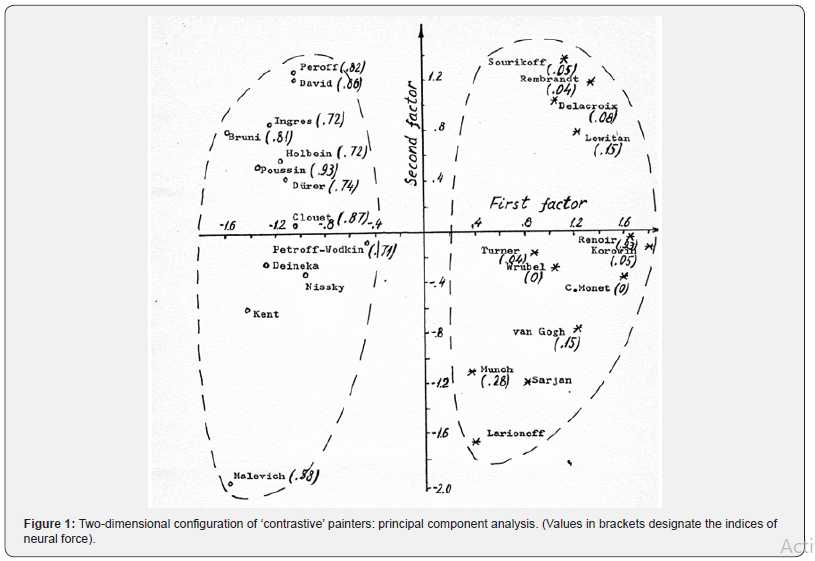

Figure 1 presents two-dimensional configuration – the result of principal component analysis which used averaged estimations put by all experts to creativity of 40 eminent painters, over the above 22 parameters. [Here out of the above mentioned preliminary list of 40 ‘contrastive painters’: 20 left-hemispherical and 20 righthemispherical ones – only 26 painters are shown – those which occurred, on the basis of several quantitative arguments, really ‘the most contrastive] [6] (Figure 1).

Considering the first factor (horizontal axis), we see two ‘clouds’ designated by dotted lines: the cloud of 13 left-hemispheric painters and the ‘cloud’ of 13 right-hemispheric ones; they show no overlapping, possessing different positions along the axis of this factor. It was named the ‘factor of asymmetry.’ The real existence of this factor was confirmed by several methods, e.g., by very high correlation between the values of the painters’ indices of asymmetry (calculated on the basis of 10 parameters – see Petrov & Boyadzhiyeva, 1996) – and their horizontal co-ordinates. [For 26 painters presented at Figure 1, Spearman coefficient of rank correlation between these rankings, equals 0.85 – significant at the level better than 1%.] Other factors do not relate to our problem. But how to identify the parameters responding to the phenomenon of ‘neural force’ discussed? [7,8]

Internal links in the sea of empirical data. Indices of ‘neural force’

At least some of the parameters seem to be reflecting the phenomenon of ‘neural force’:

– The parameter No. 1 (Inclination to normative work

– Inclination to originality); really, in order to introduce innovations, it is desirable to possess rather high ‘force potentialities’;

– The parameter No. 5 (Laconic expressive means – Diversity, variety of expressive means); in fact, diverse expressive means evidence in favor of the need for richness of perceptual reactions;

– The parameter No. 21 (Absence of gradations within one color – Inclination towards large number of color gradations), and

– The parameter No. 22 (Smooth painting – Texture painting).

All four parameters possess high loads onto the first factor. But do these parameters work together in reality? To answer this question, it seems prospective to resort to the help of more expanded sources of empirical data. Exactly such was the second source – data over 10 ‘most important’ parameters of 200 eminent European painters (including Russian ones), involved in a large evolutionary investigation; among these parameters we find the above four ‘suspected’ features (see Petrov & Boyadzhiyeva, 1996, pp. 136-141). Are they linked with each other? In order to examine their mutual links, we divided all 200 painters into sub-massifs, in accordance with appropriate national schools of painting.

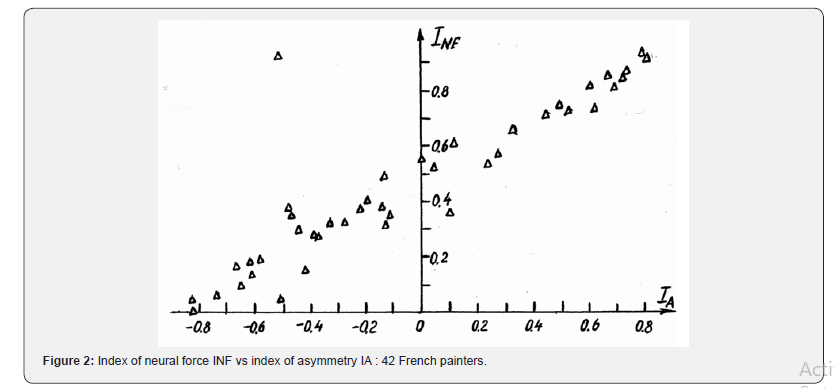

We examined several such sub-massifs – e.g., the above four parameters of 42 painters representing French art. It occurred that Citation: Vladimir M Petrov, Lidia A Mazhul. Back to Hippocrates? Information-Based Approach to Subjects’ Qualities, their Statistical Estimations, and Evolution . DOI: 10.33552/ABBA.2019.03.000570. Page 4 of 4 these four parameters do really tightly correlated with each other. Thus, Spearman coefficient of rank correlation between parameters No. 1 and 5 equals 0.77, between No. 1 and 21 – 0.53, between No. 1 and 22 – 0.79 (all the values are significant at the level better than 1%). Analogous tight inter-parametrical links, as a rule, were observed on the material of other sub-massifs. Their ‘mutual attraction’ permits to suppose the existence of a certain ’averaged value’ which would reflect the phenomenon of ‘neural force.’ The values of appropriate indices (i.e., the results of averaging over the above four parameters) is also presented at Fig. 1 (in brackets. for painters which were involved in the procedure of principal component analysis). Exactly these values can be named ‘indices of neural force,’ characterizing the creativity of each painter. The index of ‘neural force’ can vary in the range from zero (representatives of ‘weak’ type) to unity (‘strong’ type).

The real importance of this index was confirmed by several methods. However, the most interesting feature of this index is nothing else that it is almost coinciding with the index of asymmetry. Thus, out of 26 ‘contrastive painters’ shown by Figure 1, for 21 of them their ‘indices of neural force’ were calculated, and their ordering was compared with their ranking over the ‘indices of asymmetry’: coefficient of rank correlation occurred to be about 0.85, this value is significant at the level much better than 1%. [A propos, the links between the four parameters selected, are so tight, that it might be sufficient to average the values of only two out of them: if to use only the parameters No. 21 and 22, – then the correlation would become only slightly less featured: 0.80, this value being also statistically very highly significant.]

Interesting is the fact that all painters of the ‘left cloud’ possess rather large ‘neural force’ (more than 0.50), whereas almost all painters belonging to the ‘right cloud’ (except Renoir) are marked with small ‘neural force’ (less than 0.27) (Figure 1).

To illustrate the strict link between hemisphericity and ‘neural force,’ Fig. 2 presents the data for the above submassif of 42 French painters: their indices of ‘neural force’ – in function of their indices of asymmetry. This dependence is evidently linear; in other words, these two indices differ only in their absolute dimensions, i.e., they are practically identical.

At least three conclusions can be made on the basis of our measurements. Firstly, rather important is the phenomenon of mutual attraction of various parameters, their inclination to one of the poles: weak or strong. Secondly, the phenomenon of “neural force’ plays different role in different kinds of activity: in musical creativity there exists a separate factor reflecting this phenomenon, whereas in painting it is simply a constituent of the phenomenon of functional brain asymmetry. Generally speaking, such important evolutionary reason as the need for ‘divergent splitting’ of any system (see, e.g., Petrov, 2007) is simply ‘looking for the most convenient place’ for dwelling? And it finds this ‘dwelling place’ either in the phenomenon of hemisphericity (in case of creativity in painting), or in its own, ‘autonomous’ factor (‘built’ especially for this need, as it was in case of musical creativity), or perhaps, in some other phenomena? Finally, certain links between this phenomenon and some other substantial features of human activity, can cause various contradictions, and perhaps, namely here are the keys for various riddles and dangerous trends in our social life, international relations, etc.? In any case, further investigations in this field seem to be rather prospective.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Golitsyn GA (1997) Information and creation: On the road to integral culture. Moscow: Russky Mir, (in Russian).

- Golitsyn GA (2013) Emotional states: informational typology, regularities of formation, orientation of art. In: VM Petrov, AV Kharuto, NN Korytin (Eds.), Quantitative methods in art studies. Proceedings of the international conference in memory of German A. Golitsyn, 20-22 September 2012. Yekaterinburg: Artefact Publishers, Russia, pp. 45-49 (in Russian).

- Golitsyn GA, Petrov VM (1995) Information and creation: Integrating the ‘two cultures.’ Basel; Boston; Berlin: Birkhauser Verlag.

- Mazhul LA., Petrov VM, Mazhul KM (2016) Correlation-based measurements: The concept of ‘neural force’ revisited. In: Metrology and Metrology Assurance. Proceedings of the 26th National Scientific Symposium with international participation. September 7-11, Sozopol, Bulgaria, pp. 292-298.

- Petrov VM (2019) Informational mechanisms created while biological evolution: Deductive ‘construing’ – from elementary cells to intuition and harmony. Annals of Biostatistics and Biometrics Applications No. 3.

- Petrov VM (2007) The Expanding Universe of literature: Principal long-range trends in the light of an informational approach. In: L Dorfman, C Martindale, V Petrov (Eds.), Aesthetics and innovation. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 397-425.

- Petrov VM, Boyadzhiyeva LG (1996) Perspectives of art development: Methods of forecasting. Moscow: Russky Mir, Russia (in Russian).

- Petrov VM, Mazhul LA (2019) Mighty hemisphericity: From socio-psychological waves to creative longevity. In: In: L Dorfman, C Martindale, V Petrov (Eds.), Integrative explorations of the creative mind. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 64-78.

-

Vladimir M Petrov, Lidia A Mazhul. Back to Hippocrates? Information-Based Approach to Subjects’ Qualities, their Statistical Estimations, and Evolution.

Psychology, Systemic-information approach, Statistics, Neural typology, Painting creativity, Expert estimations, Principal component analysis, Indices

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.