Research Article

Research Article

A Mathematically and Clinical Interpretable Approach to Identify Disease Sub-Groups from Longitudinal Patient Trajectories

Marcela Cespedes1*, Timothy Cox2, Cai Gillis3, Nancy Nairi Maserejian3, Hamid Sohrabi4, Christopher Fowler5, Paul Maruff6, Stephanie Rainey-Smith7, Colin Masters5, Jurgen Mejan-Fripp1 and James Doecke1

1Australian E-Health Research Centre, CSIRO, Herston, Queensland, Australia

2Australian E-Health Research Centre, CSIRO, Parkville, Victoria, Australia

3Biogen, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA

4Murdoch University Centre for Healthy Ageing, Murdoch, Western Australia, Australia

5Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health, The University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

6Cogstate Limited, Melbourne, Australia

7Centre of Excellence for Alzheimer’s Disease Research and Care, School of Medical and Health Sciences, Edith Cowan University, Joondalup, Western Australia, Australia

Marcela Cespedes, CISRO Health & Biosecurity, Australian E-Health Research Centre, Surgical Treatment and Rehabilitation Service (STARS), 296 Herston St, Herston, Queensland 4029, Australia

Received Date: November 09, 2025; Published Date: December 02, 2025

Abstract

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease that may take decades to develop from the Cognitively Unimpaired (CU) to clinical dementia stages. Understanding the nature of this disease development is central to clinical pathological models of AD. Sigmoid curves provide a mathematical model to describe progression through the all stages of AD. They also provide a basis for risk estimates for progression between pre-clinical and symptomatic disease stages which can be applied to biomarkers or clinical markers. Using longitudinal cognitive data from the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) study of ageing a method for identification of participants with progressive cognitive decline prior to clinical symptoms was developed. First, a data driven approach was used provide estimates of sigmoid inflection points for cognitive and clinical symptoms through the use of derivatives. Second, participants annual rate of decline and three time-point mean values were mapped to the sigmoid first derivative, allowing for participants’ disease age to be offset from their chronological age. Inflection points were then calculated via the third derivative. Participants whose longitudinal trajectory crossed the first inflection point were classified as having cognitive decline, whilst those whose disease trajectory did not cross were classified as stable. Variability was estimated using 1,000 bootstrap iterations. This approach was then used to identify individuals with progressive cognitive decline on the basis of their scores on the Pre-clinical Alzheimer’s Cognitive Composite (PACC) score. From the complete cohort, 619 (59%) were classified as having cognitive decline, 287 (27%) as CU and stable, and 143 (14%) in the clinical disease group. The inflection point threshold was found to be at the disease age of 70.76 years (standard deviation of 0.21 years). Applied to real-world data, this fast and simple data-driven approach dis-aggregates longitudinal trajectories into three classifications using only participant age and cognitive data.

Keywords:Longitudinal analyses; clustering; Alzheimer’s disease; logistic model

Introduction

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia worldwide [1]. The clinical and biological changes that characterize AD develop in a non-linear longitudinal manner, with amyloid accumulation beginning 20 or more years before cognitive impairment becomes apparent [2-4]. Due to the subtle nature of biological and clinical changes in the early stage of AD, along with considerable variability in estimates in disease progression between adults, the development of models to understand the long- term dynamics of these changes may provide information about the best time opportunity for treatment and also for the design of clinical trials of drugs developed to change such trajectories [5]. The long and complex trajectory of biological and clinical changes in AD has been well studied [6-8]. The seminal paper by Jack, et al. 2010 [9] provide a foundation for understanding the progression of biomarkers and clinical markers, as well as their relationship to one another, which in each case were described using a sigmoid curve or trajectory. In this model amyloid-β (Αβ ) begins to accumulate which is followed by the formation of tau tangles, loss of brain volume and ultimately cognitive impairment. This initial pattern described by Jack et. al. 2010 [9], which follows a basic sigmoidal type trajectory has been validated using different biomarkers which provide contributions to AD longitudinal mapping [10-12].

Most studies assessing cognitive decline across the AD continuum, have derived criteria to identify cognitive impairment, whereby participants progress during the study from either Cognitively Unimpaired (CU) to Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) or from MCI to AD. Such criteria are often clinically based rather than data driven, and hence may miss subtle changes in cognition. Machine learning methods have been useful to demonstrate group wide changes in progression [13,14]. In this work we provide a useful addition to such methods to both place participants onto a disease progression pathway and define their binary progression status using inflection points. Whilst the work from Jack, et al. 2010 [9] conceptualized the development of AD through the sigmoid curve, few have provided a clearly defined model which can be applied to prospective data, and none have classified participants into binary classification of disease progression. Works which have assessed the trajectory of AD biomarkers including Positron Emission Topography (PET) [15- 17], cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Αβ [3,15] and plasma biomarkers [18] as well as cognitive outcomes [19] defined the shape of the trajectory, however did not assign a disease age akin to chronological age, and did not classify participants into groups based on their point on the disease trajectory.

Using data driven methods to identify groups of participants along the stages of the AD continuum for various targeted outcomes can greatly improve our understanding of the disease trajectory, and can provide useful information for clinical trials. Given the recent success of clinical trials for the treatment of AD in participants with either MCI or mild AD [20-22], these trials largely depended on the careful recruitment of participants at specific AD stages that would respond to treatment over the course of the trial observation period. Identification of participants along specific disease stages for clinical endpoints such as the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE [23]) and Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes (CDR SB [24]) using data driven methods has yet to be documented. Moreover, a generic and robust statistical approach suitable for more sensitive measures for clinical progression earlier in the disease course [25] is needed, with the introduction of clinical trials in pre-clinical disease (AHEAD 3-45 study [26,27]), whereby all participants are CU but have amyloid pathology. For such trials to succeed, it is imperative that appropriate non-linear models of progression for participants are defined prior to the trial. The method here provides key points on population-based models to classify participants into specific groups of progression, allowing for a more carefully designed trial.

Amyloid accumulation is one of the earliest biomarkers to show changes along the disease continuum, hence, therapeutic intervention targeting the Αβ pathway before significant and irreversible neurodegeneration may provide an approach to prevent or delay cognitive decline and dementia [22,26, 28,29,30,31]. Finding a marker which is accurate to assess a participants point on the disease continuum during the early disease stages of amyloid accumulation is key to then ascertain an appropriate and optimal treatment window. The Pre-Clinical Alzheimer’s Cognitive Composite (PACC) score is a measure of amyloid- related neural loss [32,33] which can detect the earliest signs of cognitive decline, whilst other cognitive tests appear unaffected [32] and for this reason, may be a suitable endpoint for early AD trials. Currently, inclusion criteria for clinical trials for AD are taken from cross sectional visits, without information on each participant individuals’ trajectory. Analyses are then typically performed during the trial using either linear mixed effects models or mixed model repeated measures assessment. This therefore assumes that the person is theoretically at the same stage along the sigmoidal trajectory where they will continue to decline.

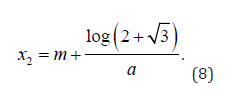

There is however, wide variation in decline rates among clinical trial candidates, with a proportion of participants in both treatment and placebo not declining, or even improving as seen in the CLARITY trial [34]. Such variations could be due to inclusion/ exclusion criteria, but would be better accounted for by employing novel approaches to understand trial candidates at a specific point on the disease trajectory. In the current work, we demonstrate a novel approach to map participant cognition to the sigmoid curve originally proposed by Jack, et al. 2010 [9], and classify participants into three latent groups: 1) those with stable cognition (stable), 2) those past the first inflection point and experiencing consistent decline in cognition (cognitive decline) and 3) those past the second inflection point at the lower part of the trajectory (poor cognition/dementia) independent of participants clinical diagnosis. Section 2 describes the case study and methodology for our proposed approach, with relevance to clinical AD features. Section 3 presents the simulation study conducted to validate our approach. Section 4 describes our approach applied to the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) study of ageing, specifically on the AIBL PACC score. Section 5 presents a discussion and motivation of future work.

Materials and Methods

AIBL Case Study

The AIBL study is Australia’s largest ongoing observational study [35] designed to investigate AD progression from preclinical to clinical stage and collects a variety of demo- graphic, genetic, blood, cerebrospinal fluid, neuroimaging and cognitive data. The AIBL study includes participants across the entire disease continuum, with an established and comprehensive database of information which characterizes the pathological and clinical changes in adults 60 years or older. The AIBL study was established in 2006 and consisted of 1,176 participants at inception; 768 CU participants, 133 participants with MCI and 211 with AD. Participants were examined at approximately 18-month intervals, with measures of imaging, cognition, lifestyle and biofluids collected at each visit. Clinical classification was made blind to imaging/biofluid measurements, taken solely from the cognitive battery of tests and the subjective opinion of the expert panel of clinicians including neuropsychologist, pathology and a psychiatrist. For a participant to progress from CU to MCI, the participant needs to meet multiple criteria, including declining in at least two cognitive domains by a minimum of 1.5 standard deviations below their previous assessment score, have altered test scores due to a separate disorder or injury (including traumatic brain injury), not have difficulties in their activities of daily living which would indicate functional impairment, and be in agreement with the opinion of the expect clinical panel.

For a participant to progress from MCI to AD, they must also show evidence of functional impairment, with altered test scores due to a separate disorder or injury (including traumatic brain injury). Currently in Australia, deterioration from healthy ageing, evolving to MCI and onto dementia is still predominately assessed by extensive neuropsychological assessments in secondary care [36]. Performed on an individual to assess global and specific cognitive domains, these assessments provide a cognitive score, which quantifies the level of cognitive impairment. The PACC score is designed to detect subtle cognitive deterioration in asymptomatic individuals [32], specifically at the pre-clinical stage and has been validated in multiple cohorts [37]. In these early asymptomatic stages of AD, CU participants can deteriorate in PACC score, but other AD related assessments which are designed to measure later stages of the disease continuum may appear unaffected [12]. Thus, it is important to utilize measures which have been specifically designed for different stages of disease continuum.

Sigmoid Algorithm

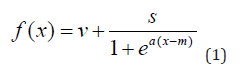

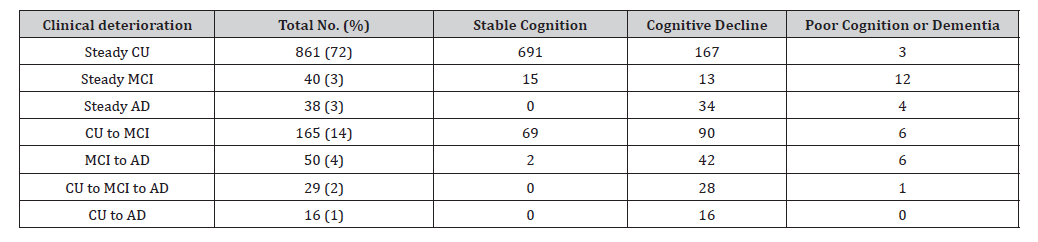

The mathematical expression

defines a one-to-one function for the cognitive outcome f (x). This is a monotone decreasing bounded function which expresses the non-linear association between y and a participants disease age x as shown in Figure 1. Note that when x = m, f (m) = v + s / 2. Due to a complex interaction of a multitude of demographic, genetic, lifestyle and other factors, participants can commence along the AD pathway at different chronological ages. Via the transformation of this approach, we map participants from their chronological age to a disease age which participants deteriorate along the sigmoid curve. Normalized composite cognitive scores measured cross-sectionally typically follow an approximate Gaussian distribution, in that they are continuous and unimodal in distribution. The AIBL PACC follows this pattern and for this reason numerical transformations were not required. Other cognitive scores such as the MMSE, are discreet and bounded with a minimum and maximum of zero to thirty. For such clinical biomarkers, numerical transformations such as standardization are required in order map individuals to the continuous sigmoid curve.

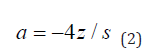

Parameters v, s and m are derived from participant level empirical summaries and have clinically related interpretations. The vertical span of the sigmoid function, s, is computed to be the difference between the 90th and 1st quantiles. The vertical shift of the sigmoid denoted by v, is the 90th quantile minus s. The mid-point of the sigmoid expression m is the overall cohort mean age. To estimate the sigmoid curve’s fastest rate of decline, or steepness, a suitable quantile from the participants individual slopes is selected, z. The point at which the sigmoid has the largest rate of decline a, is computed as

Once all the parameters are estimated for expression (1), a unique mathematical sigmoid formula is available for the cognitive outcome in the cohort of interest.

The sigmoid curve describes all stages of cognitive decline for the entire AD disease course [11,10], (Figure 1 shows the theoretical AD sigmoid curve). Early on, in the asymptomatic stages of the disease and prior to extensive amyloid accumulation, individuals have stable cognition reflected by high cognitive scores with little or no decline in scores during this disease stage. PACC scores from participants with pre-clinical disease (presence of amyloid plaques but asymptomatic) start to depart from this stable cognition stage during the early part of the trajectory. Participants experiencing cognitive decline in the symptomatic stages typically follow a non-linear trajectory shown by rapidly deteriorating cognitive scores. The midpoint of the sigmoid trajectory is the point of fastest decline at the disease age of m. Towards the end stage of the disease, participants test scores may reach a potential “floor”, whilst other scores continue to decline (MMSE reach a floor of zero). Here cognitive performance may start to plateau and in expression (1) this is shown to be past the second inflection point, as the stable but server cognitive impairment phase (9) (classified in the remainder of this work as poor cognition or dementia).

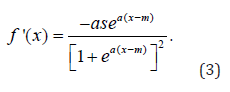

Mathematically these inflection points are computed from the first, second and third derivatives of expression (1). The first derivative is of the form

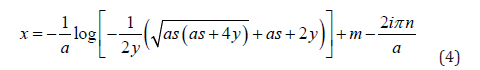

Let y = f '(x) , solving for x yields

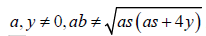

Where a, y ≠ 0, ab ≠

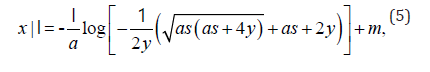

As we are seeking a clinically practical solution, in this work we only consider the real component of expression (4). Typically, inverse functions are one-to-one, that is for every unique value in x, there is one, and only one solution. For this reason, we introduced a further modification to map participants chronological age to a disease adjusted domain by incorporating a participants mean of the outcome. Hence expression (4) is modified to

where I is an indicator variable. If a person’s average outcome is less than f (m) , then I = −1 which implies this person is shifted to a later disease age. Otherwise, I = 1 when a person’s average outcome is greater than or equal to f (m) , and this shifts an individual to an earlier disease age. The size of the offset from a participant chronological to disease age is contingent on their annual rate of decline. Once all participants have a corresponding disease age, their longitudinal trajectories are shifted by this offset and are mapped onto the sigmoid disease curve.

Classification of Participants

The peaks at which there is a change in the acceleration of the sigmoid curves can be found by the inflection points of the second derivative of equation (1). These peaks align with the points in the AD disease curve where the acceleration in the sigmoid curve changes, from stable cognition to cognitive decline status 1 (x ) as well as from a cognitive decline to poor cognition/ dementia 2 (x ) whereby a participants’ cognition has either plateaued or is close to the plateau at the bottom of the range. Refer to Appendix A for second derivative expression.

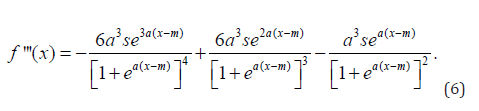

To find the points of inflection for the second derivative, the third derivative is computed and solved for x. The third derivative of (1) is

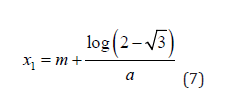

The real components and clinically meaningful solution to x1 and x2 from (6), are

and

The sigmoid inflection points x1 and x2 can be shown by the black vertical dashed lines in Figure 1. Participants with entire longitudinal disease adjusted age trajectories which lie to the left of x1 are classified as having stable cognition. Participants with trajectories that cross x1 at any time point are deemed as having cognitive decline. Participants past this point who have already deteriorated are known to have lower-than-average mean cognitive scores as well as comparatively low annual rate of decline. These participants can be identified as those whose entire trajectories lie to the right of x2 and are classified as having poor cognition/dementia.

Statistical Analysis

The algorithm described in Section was implemented in opensource R software [38]. R packages were used facilitate the data processing, model implementation, visualisation and all analyses conducted in this work [39-45]. Scripts to simulate synthetic data and source code for the sigmoid algorithm are available on the CSIRO Bitbucket repository at https://data.csiro.au/collection/ csiro:70027v2.

Simulation Study

In order to validate the methodology, a simulation study was undertaken to enable the comparison of current naive/ empirical summary approaches to identify cognitive groups. In this work 1,000 bootstraps were conducted to derive uncertainty estimates for the sigmoid parameters. Each bootstrap comprised a random sample (without replacement) of 80% of the simulated individuals including all their longitudinal observations, and the sigmoid method and cognitive group classification were estimated. This approach also enabled the assessment of the method to classify individuals at every post-bootstrap iteration and identify participants who may have different cognitive group classifications. Similar to the AIBL study, participants baseline ages were generated from a Gaussian distribution with a mean of 70, standard deviation of 6.6 years and each participant had two or more follow- ups. A linear mixed effect model was fitted to the AIBL study data, and the parameters of this model, namely participant age and clinical diagnosis, were used to generate synthetic participant level data.

Similar proportions of stable CU, MCI and AD participants as well as participants who deteriorated throughout the study (CU to MCI and MCI to AD) as observed in AIBL were generated in our synthetic data set. Cognitive outcomes are highly variable and often consist of variation between and within participants. For this reason, these sources of variation were incorporated in addition to residual variance. Participant withdrawal or drop out is a common consequence in longitudinal studies, particularly in older adults, as such similar rates of drop outs observed in AIBL were incorporated into our synthetic data set. In a similar manner as previous work [35] and for comparison, a naive method to identify cognitive decliners from non-decliners was applied. Participants who deteriorated clinically from CU to MCI, and from MCI to AD were classified as having shown cognitive decline. Participants who were in the process of deteriorating or already with clinical AD (stable MCI and AD) were also categorized as cognitive decline. Non-decliners were participants who were stable CU. This naive approach is irrespective of their overall annual rate of decline or their overall mean cognitive assessment. Under this criterion, simulated data included 627 (42%) as cognitive decliners and 873 (58%) as non-cognitive decliners.

Simulation Results

In total AIBL PACC scores for N = 1, 500 participants longitudinal data were simulated for up to 7.5 years with follow-ups every 1.5 years. Participants along the entire AD continuum were generated including those with stable CU (N = 1, 125, 75%), stable MCI (N = 60, 4%) and stable AD clinical diagnosis (N = 45, 3%). Synthetic participants which clinically deteriorated throughout the study were also included, such as those who deteriorated CU to MCI (N = 210, 14%) and MCI to AD (N = 60,4%). The mixed effects model included covariates of baseline age, time in years of participants in the study, clinical conversion classification and the interaction of time and clinical conversion as main effects. The fixed effects as well as the intercept and slope random effect estimates from this model were used to generate the outcome for each participant. Refer to Supplementary Appendix B for model results and summaries of simulated data. Our synthetic data set incorporated similar patient dropout rates as the AIBL study, with 22% and 42% of patient drop out by the fourth and final time points, respectively. Figure 2 shows both the longitudinal AIBL PACC data trajectories and simulated trajectories.

Simulated longitudinal data classification

Applied to the whole synthetic data set, the 1% quantile (z = −0.273 applied to expression (2)) was used to select a lower annual rate of decline [Supplementary Figure 2] which determined the steepness of the sigmoid curve. Empirical synthetic data summaries were used to compute sigmoid parameters a, m, v and s. Synthetic participants were then mapped onto the first derivative [Supplementary Figure 3], and hence their respective disease adjusted ages were computed. The cognitive classification cut-offs x1 and x2 were found to be 66.95 and 78.56 years respectively. We identified 1,249 (83%) with stable cognition, 226 (15%) with cognitive decline and 25 (2%) with poor cognition/dementia. Disease adjusted trajectories mapped onto the sigmoid function for synthetic participants are shown in Supplementary Figure 4. Table 1 shows the number of simulated participants categorized as cognitive decline status via the naive/ traditional approach [35] on the rows, as well as via the proposed sigmoid method shown on the columns.

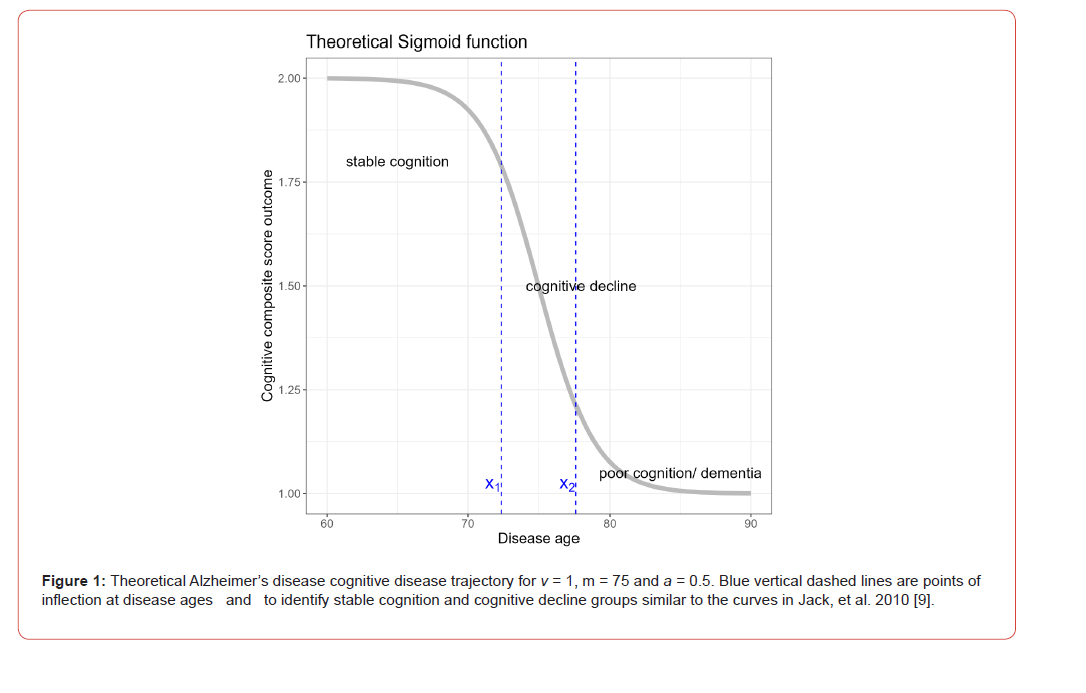

Table 1: Number of Subjects at Each Site.

Both approaches agree that 1050 (70%) of synthetic patients were cognitively stable and 154 (10%) of the cohort had cognitive decline. Discrepancies detected found that there 199 (13%) of participants were categorized as having cognitive decline, but the sigmoid approach classified these individuals as stable cognition. A visual comparison of this group in Supplementary Figure 10, shows that trajectories for these individuals were very noisy with many following a ‘W’ or ‘N’ longitudinal trajectory or many placed just left of the sigmoid inflection point (at 66.95 years), and hence, narrowly missed the cut-off to be considered as cognitive decliners. These results illustrate an advantage of the sigmoid method, that such thresholds are data driven by the entire cohort, including those individuals who show clear and rapid deterioration, and hence, our approach can untangle between normal or negligible decline from those observed with rapid cognitive deterioration, using only age and outcome measures.

Similarly, Supplementary Figure 6 shows the trajectories for 72 (5%) synthetic individuals classified as cognitive decline by the sigmoid method, but stable cognition via the traditional approach. Via the sigmoid approach these individuals were split into two groups, those with trajectories that crossed the first inflection point at them later follow-up stages and those with lower-than-average outcomes, who crossed the second inflection point. Furthermore, we note that under the traditional approach, participants who have low cognition are considered as having cognitive decline, whereas the sigmoid approach identified these individuals as being in the poor cognition/dementia continuum, with a much later disease adjusted age as shown in Supplementary Figure 7 as these individuals did not show rapid annual rates of decline, however their overall mean outcome was lower than average.

Simulated bootstrapped results

There were 1, 418 (95%) synthetic individuals who had consistent cognitive classification throughout all bootstrapped iterations. The proportion of participants with cognitive decline, in Supplementary Figure 9, shows the consistency of the sigmoid algorithm to categories individuals. The uncertainty for each bootstrapped sigmoid parameter allowed for the computation of 95% confidence intervals, as shown on Supplementary Table 3, which included the stable cognition and cognitive decline group cut-off values x1 and x2 . These results show the bootstrap results were very similar to the whole synthetic data application. We found 82 (5%) of participants with non-consistent classifications. The bootstrapped trajectories of these individuals and respective cut-off thresholds are shown in Supplementary Figure 10. These results show that majority of these individuals had either ’W’ or ’N’ shaped longitudinal trajectory, meaning their estimated annual rates of decline was close to zero or positive, and they did not have a consistently high or low synthetic outcome mean. Other misclassified individuals had disease adjusted ages near the cut-off values, resulting in different classifications at different bootstrapped iterations.

Sigmoid approach on AIBL case study

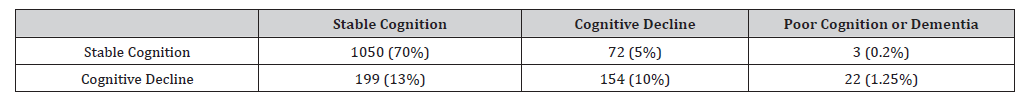

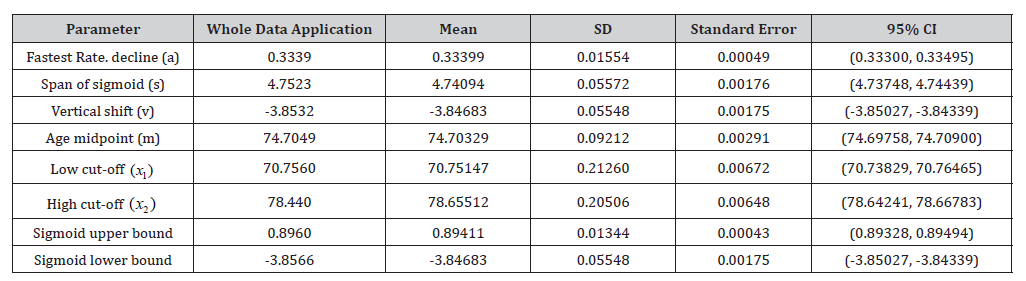

Our approach was applied to longitudinal AIBL PACC scores of N = 1, 199 individuals. Data was obtained at baseline and at collections approximately 18 months apart for a minimum of two and a maximum of ten follow-up visits. Only participants 55 years or older with three or more AIBL PACC scores at each collection were retained. The 1% quantile (-0.3967) over participant slopes was selected as z in expression (2), see Supplementary Figure 11. Other empirical summaries were used to compute the remainder of the sigmoid parameters, as shown on Table 3. Once the sigmoid curve was derived for the cohort, the respective derivatives and cutoffs were computed. The cut-off from stable cognition to cognitive decline was x1 = 70.76 and poor cognition/ dementia individual’s cut-off was x2 = 78.74 disease adjusted years. We can infer that the difference in these cut-off values, 7.99 years, is an approximate duration at which participants decline in AIBL PACC scores. Using the first derivative Supplementary Figure 12, participants were mapped onto the sigmoid curve, as shown in Figure 3. Using the AIBL PACC, we identified 777 (65%) and 390 (33%) as having either stable cognition or cognitive decline respectively. Table 2 shows the cohort sizes across various clinical diagnosis groups.

Table 2: Sample sizes for clinical and sigmoid methodology groups and proportion in parenthesis. Abbreviations: cognitively unimpaired (CU), mild cognitive impaired (MCI), Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Table 3: Longitudinal AIBL study and bootstrapped sigmoid parameter summaries including standard deviation (SD) and 95% confidence interval (CI) reported.

There were also 32 (3%) individuals in the poor cognition/dementia group who had positive or small annual rates of decline as well as overall low AIBL PACC means. As shown in Supplementary Figure 15, the chronological age trajectories show these individuals to have lower than average mean AIBL PACC scores and their noisy trajectories do not fit the standard cognitive decline profile. The left of [Figure 2A] shows the raw chronological age participant disease trajectories, and via the algorithm, we shifted these trajectories as shown in Figure 3. Note that y-axis (AIBL PACC score) remains unchanged in both plots, the only change via the sigmoid method is the shifting of participant to a younger (left) or older (right) disease adjusted age. The participant means versus slope scatter plot [Supplementary Figure 14] shows ranges and variability in the cohort, as well as the selection of slope and mean outcome values used to define the distinction of the stable cognition from the poor cognition/dementia group the outcome value of f (m) . For further analyses on the utility of our method, we explored cognitive decline individuals who underwent a PET amyloid scan.

As accumulation of amyloid can begin up to 30 years before full clinical AD is diagnosed, this biomarker is increasingly of interest in early AD intervention. A subset of 965 AIBL individuals analyzed in this work also underwent at least one PET scan. These participants were categorized as PET Αβ positive (Αβ +) if at any visit their PET amyloid accumulation measured by centiloid (CL) was greater than 15. In total there were 450 individuals identified as Αβ + . Of the 390 cognitive decline individuals, 322 had at least one or more PET scan and 68 cognitive decliners did not undergo any PET scans. To assess centiloid levels for cognitive decliners over increasing disease age, we categorized disease age into six age bands and reported mean CL values and respective standard deviation for each age band, refer to Supplementary Figure 13. Mean CL was low in the first two age bands (less than 63 disease age years) with overall means of 10.9 & 9.7 CL. There was a notable increase in CL with increasing age bands towards the inflection point of 16.6, 30.9 to 45.1. The age band after the inflection point, with a disease age of 72 and onwards, had a mean CL of 72.2.

Bootstrapped AIBL results

Cognitive classification concurrence can be seen in Supplementary Figure 17, as shown by the proportion of classification for each AIBL participant. In this work, we found N = 1, 154 (or 96%) individuals with consistent cognitive classification. There were 45 (4%) individuals with multiple cognitive classifications, Supplementary Figure 18 shows their disease adjusted age longitudinal trajectories, as well as the bootstrapped cut-offs. Similar to the simulated analyses, we found that individuals with ’W’ or ’N’ shaped trajectories to be misclassified, as well as individuals whose disease adjusted ages were close to the cut-off values. Interestingly, our results also identified five individuals with steep upward AIBL PACC trajectories, whose mean outcomes were close to f (m) in value. These individual’s classification varies at the two extremes of the disease stages, from stable cognition to poor cognition/dementia groups. We note that during each bootstrap iteration f (m) which is used as the indicator variable in expression (4) slightly varies, as do all sigmoid parameter estimates, including cut-off estimates x1 and x2 at every bootstrap iteration. Due to the overall AIBL PACC mean for these individuals being so close to x1 and/or x2 as well as variation in participant age offset via f (m) , these individuals were shifted accordingly. Bootstrapping was used to estimate the mean parameter values and corresponding 95% confidence intervals, shown in Table 3. The bootstrapped estimates align with the estimates of the method applied to the AIBL study cohort.

Discussion

The aim of this project was to develop an application using existing mathematical methodology to classify older adults into three separate groups with respect to a hypothetical cognitive trajectory that was expressed mathematical as a sigmoidal curve. We theorized that by applying the process to longitudinal cognitive data from a large study of ageing, we could identify those older adults whose cognitive scores move past the inflection point on the sigmoid cognitive trajectory prior to formal clinical classification of

MCI. Amongst those participants who were CU for all collections within AIBL, we identified 16% who had cognitive scores which were past the inflection point, and were experiencing objective cognitive decline prior to being formally classified as having MCI. Such participants have cognitive scores then which align with the standard cognitive decline seen in AD and can be monitored closely in future years. Additionally, for those participants with MCI, the method classified 43% with stable cognition. Tracking disease progression has been well characterized over the years, with separate groups providing methods and techniques on how to measure rates of decline, define when the levels of Αβ become abnormal, and then how long it takes between when Αβ become abnormal whilst cognition is still normal (pre-clinical phase) through to when cognition becomes impaired (prodromal disease). The original hypothetical model for disease progression proposed in 2010 by Jack, et al. [9] defined the sigmoid type trajectory, with Αβ becoming abnormal first, followed by taumediated neuronal injury and dysfunction, a loss of brain volume, followed by decline in memory and lastly clinical function.

Updates to this model, along with data from the DIAN study [11] demonstrated changes in CSF Αβ 42 and tau from 15-30 years prior to the estimated year from expected onset. Villemagne et. al. (2013) [3] demonstrated that using 3-4 years of PET-Αβ data from participants of the AIBL study was enough to provide a reliable model of change in Αβ across the full AD continuum, determining rates of change per year, and disease time for each participant. Another method by Jack et. al. (2013) [46], although slightly different, achieved similar results and demonstrated the pattern of change in Aβ over the disease continuum fit a sigmoid type curve. More recently a method to align participants to an AD trajectory and define and amyloid time or amyloid clock was published [47]. The method derived an estimated time symptom onset, which has been used across cognition [48], CSF and blood biomarkers [49]. All methods describe either the trajectory of the biomarker of interest, or the time to symptom burden, without a formal classification at a point on the curve by which a participant can be said to have progressed from a theoretical “stable” state, to a disease progression state. The inflection point identified here (bootstrap average) for the PACC score occurred at an average population disease age of 70.8 years of age (SD: 0.2), which was almost the same as from using the single run estimate (70.76 years of age).

For participants who remained cognitively stable over the study, the average follows up time ranged between 3 and 15 years, with PACC scores slowly decreasing Figure 3, indicating a long enough follow-up time to discern AD-related cognitive decline. Given the inherently complex nature of the disease, it is important to be able both track individual cognitive decline and define optimal points for participants to be treated. Due to the short clinical trial period with respect to a disease which may span three decades, successful trials have thus far focused on participants who were at a very specific disease stage, either MCI due to AD or mild AD in addition to testing positive for specific AD biomarkers. End points for these trials include cognitive assessments which target a measurement on the progression of established AD such as the Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of boxes. Trials for a different group of participants with preclinical AD are currently under way, and these use very different cognitive outcome measures such as the PACC score. Using the application of this method allowed the identification of participants with a cognitive trajectory consistent with that leading towards AD, both in pre-clinical and prodromal stages. It also identified those participants who had scored lower on cognition at baseline, but who failed then to progress to MCI or AD in the coming years.

One benefit of using longitudinal cognitive data from the AIBL study is that for those with cognitive decline, we were able to follow their cognitive trajectories for up to 12 years prior to the sigmoid inflection point. For participants with cognitive decline as defined here, assessment of centiloid levels across three-year age bands demonstrated the mean centiloid level to reach abnormal levels (>15CL) approximately seven years prior to the inflection point for the PACC score, with a mean centiloid level at the inflection point at approximately 45CL (SD: 49.5). The large standard deviation around each of the mean centiloid levels indicated a large proportion of variation in centiloid level for participants at the inflection point. In this work we tested the method on simulated data, using parameters derived from the AIBL study, and then compared the results from a standard approach of using a 1.5 SD decline in two or more cognitive domains. Whilst this simulated transition between CU and MCI, and MCI and AD does not mimic a real-life classification transition, it was able to validate the performance of classification using a simulated data set. Bootstrapped results from the simulated data showed approximately 5% of participants to have inconsistent classifications, with patterns of cognition representing either “M” or “W” shaped patterns, which were also seen in the AIBL data set.

Such participants were correctly classified in both simulation and AIBL data sets into the poor cognition/dementia category, whereby their cognitive trajectories do not match the typical AD trajectory. Data causing these patterns could be from natural variability of the measure, or that participants sometimes perform poorly, not due to the disease, but for other reasons unexplained by traditional measures. A major strength of this work is the simplicity of the implementation of this method. Only longitudinal participant chronological age and cognition are needed for implementation. As a minimum, we recommend at least three observations per participant, for a period of 36 or more months as an appropriate duration of to observe substantial change in AD related outcome measures. The method has utility in both research and in the clinic, whereby participant data can be added to the method, and a classification can be extracted as to where the participant is on the population trajectory. Estimates of either how long it will take to reach the inflection point, or how long ago the person passed the inflection point can be derived.

This can become complex whilst taking into account the presence of confounders such as genetic factors such as APOE ϵ4, baseline age and gender, however given these are present in the underlying data, estimates can be derived for each specific subgroup. A disadvantage of this method, due to its simplicity, is the fact that other important factors affecting AD trajectories are not included in the derivation of the participant trajectory, such as APOE ϵ4 carrier status, gender or clinical diagnosis. Furthermore, for a robust sigmoid curve and hence identification of participant groups via the inflection point, information on participants across the entire AD spectrum is needed. In summary, the work here demonstrates the application of a method which can allocate participants to groups based on their non-linear cognitive trajectory. Estimates based on the population curve can be derived to estimate where exactly on the AD trajectory they sit, and if their cognitive trajectory fits what would be expected given the population. Future work will implement the current methodology into an online application which will classify participants given a single cross-sectional point of data.

Acknowledgment: We would like to acknowledge and thank all AIBL participants and their families.

Funding: This study was funded by Biogen.

Role of Funder/Sponsor

An employee of Biogen had a role in the analysis plan, review, and revision of the manuscript but had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, and interpretation of the data; approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

CG and NM are employees of and may own stock in Biogen. HS has received research funding or personal reimbursement for research related work with Biogen, Alnylam Pharmaceuticals and Alector Therapeutics and is a director of the SMarT Minds, WA, Australia.

Appendix

Appendices for this work and R code to implement method can be found at the following link: https://data.csiro.au/collection/ csiro:70027v2.

References

- (2020) Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017-2025. World Health Organization and others.

- Koscik RL, Betthauser TJ, Jonaitis EM, Allison SL, Clark LR, et al. (2020) Amyloid duration is associated with preclinical cognitive decline and tau Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring 12(1): e12007.

- Villemagne VL, Burnham S, Bourgeat P, Brown B, Ellis KA, et (2013) Amyloid β deposition, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet Neurology 12(4): 357-367.

- Jack Jr CR, Lowe VJ, Weigand SD, Wiste HJ, Senjem ML, et al. (2009) Serial PIB and MRI in normal, mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: implications for sequence of pathological events in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 132(5): 1355-1365.

- Cespedes M, Gillis C, Maruff P, Maserejian N, Fowler C, et al. Sigmoid method- ology allows early prediction of cognitive decline towards Alzheimer’s disease across several cognitive domains. 14th Conference Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease, The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease 8(4): S142-

- Petersen RC (2010) Alzheimer’s disease: progress in The Lancet Neurology 9(1): 4-5.

- Aisen PS, Cummings J, Jack CR, Morris JC, Sperling R, et (2017) On the path to 2025: understanding the Alzheimer’s disease continuum. Alzheimer’s research & therapy 9(1): 1-60.

- Cox T, Shishegar R, Lim YY, Robertson J, Lamb F, et al. (2021) Supplement: Clinical manifestations. Alzheimer’s and Dementia 17(S6):

- Jack CR, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Shaw LM, Aisen PS, et al. (2010) Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s pathological The Lancet Neurology 9(1): 119-128.

- Bilgel M, An Y, Lang A, Prince J, Ferrucci L, et al. (2014) Trajectories of Alzheimer disease-related cognitive measures in a longitudinal sample. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 10(6): 735-742.

- Jack Jr CR, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Weiner MW, et al. (2013) Tracking Pathophysiological Processes in Alzheimer’s Disease: An Update on hypothetical model of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. The Lancet Neurology 12(2): 207-216.

- Risacher SL, Saykin AJ (2013) Neuroimaging and other biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease: the changing landscape of early Annual review of clinical psychology 9: 621-648.

- Dukart J, Sambataro F, Bertolino A (2016) Accurate prediction of conversion to Alzheimer’s disease using imaging, genetic, and neuropsychological biomarkers. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 49(4): 1143-1159.

- Li D, Iddi S, Aisen PS, Thompson WK, Donohue MC, et al. (2019) The relative efficiency of time-to-progression and continuous measures of cognition in presymptomatic Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions 5: 308-318.

- Budgeon CA, Murray K, Turlach BA, Baker S, Villemagne VL, et al. (2017) Constructing longitudinal disease progression curves using sparse, short- term individual data with an application to Alzheimer’s Statistics in Medicine 36(17): 2720-2734.

- Betthauser TJ, Bilgel M, Kosick RL, Jedynak BM, An Y, et al. (2022) Multi-method investigation of factors influencing amyloid onset and impairment in three Brain 145(11): 4065-4079.

- Schindler SE, Li Y, Buckles VD, Gordon BA, Benzinger TLS, et al. (2021) Predicting symptom onset in sporadic Alzheimer disease with amyloid PET. Neurology 97(18): e1823-e1834.

- Burnham SC, Fandos N, Fowler C, Perez-Grijalba V, Dore V, et al. (2020) Longitudinal evaluation of the natural history of amyloid-β in plasma and Brain communications 2(1): fcaa041.

- Capuano AW, Wagner M (2023) nlive: An R package to facilitate the application of the sigmoidal and random changepoint mixed models. BMC Medical Research Methodology 23(1):

- Dhillon S (2021) Aducanumab: first Drugs 81(12): 1437-1443.

- Hoy SM (2023) Lecanemab: first Drugs 83(4): 359-365.

- Mintun MA, Lo AC, Duggan Evans C, Wessels AM, Ardayfio PA, et al. (2021) Donanemab in early Alzheimer’s New England Journal of Medicine 384(18): 1691-1704.

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of psychiatric research 12(3): 189-198.

- Lynch CA, Walsh C, Blanco A, Moran M, Coen RF, et al. (2005) The clinical dementia rating sum of box score in mild dementia. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders 21(1): 40-43.

- Temp AGM, Ly A, van Doorn J, Wagenmakers EJ, Tang Y, et al. (2022) A Bayesian perspective on Biogen’s aducanumab Alzheimer’s & Dementia 18(11): 2341-2351.

- Rafii MS, Sperling RA, Donohue MC, Zhou J, Roberts C, et al. (2023) The AHEAD 3- 45 study: Design of a prevention trial for Alzheimer’s Alzheimer’s & Dementia 19(4): 1227-1233.

- AHEAD 3-45 study: A study to evaluate efficacy and safety of treatment with lecanemab in participants with preclinical Alzheimer’s disease and elevated amyloid and also in participants with early preclinical Alzheimer’s disease and intermediate amyloid, 2023.

- Bischof GN, Jacobs HI (2019) Subthreshold amyloid and its biological and clinical meaning: long way ahead. Neurology 93(2): 72-79.

- Burke AD, Goldfarb D (2023) Diagnosing and treating Alzheimer disease during the early stage. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 84(2): 46292.

- Sims JR, Zimmer JA, Evans CD, Lu M, Ardayfio P, et al. (2023) Donanemab in early symptomatic Alzheimer disease: the TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 330(6): 512-527.

- Van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, Bateman RJ, Chen C, et (2023) Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. New England Journal of Medicine 388(1): 9-21.

- Donohue MC, Sperling RA, Salmon DP, Rentz DM, Raman R, et al. (2014) The preclinical Alzheimer cognitive composite: measuring amyloid-related JAMA neurology 71(8): 961-970.

- Bransby L, Lim Y, Ames D, Fowler C, Roberston J, et al. (2019) Sensitivity of a Preclinical Alzheimer’s Cognitive Composite (PACC) to amyloid β load in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Journal Clinical Experimental Neuropsychology 41(6): 591-600.

- Swanson CJ, Zhang Y, Dhadda S, Wang J, Kaplow J, et al. (2021) A randomized, double-blind, phase 2b proof-of-concept clinical trial in early Alzheimer’s disease with lecanemab, an anti-Aβ protofibril Alzheimer’s research & therapy 13(1): 1-14.

- Fowler C, Rainey-Smith SR, Bird S, Bomke J, Bourgeat P, et al. (2021) Fifteen years of the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) study: progress and observations from 2,359 older adults spanning the spectrum from cognitive normality to Alzheimer’s Journal of Alzheimer’s disease reports 5(1): 443-468.

- Porsteinsson A, Isaacson R, Knox S, Sabbagh MN, Rubino I (2021) Diagnosis of early Alzheimer’s disease: clinical practice in The journal of prevention of Alzheimer’s disease 8(3): 371-386.

- Donohue MC, Sun CK, Raman R, Insel PS, Aisen PS, et al. (2017) Cross-validation of optimized composites for preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions 3(1): 123-129.

- (2022) R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

- Wickham H, Francois R, Henry L, Muller K, Voughan D (2023) dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation.

- Wickham H (2016) ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag New York.

- Wickham H (2007) Reshaping data with the reshape package. Journal of Statistical Software 21(12): 1-20.

- Bates DM, Machler M, Bolker B, Walker S (2015) Fitting linear mixed- effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67(1): 1-48.

- Nash JC, Varadhan R (2011) Unifying optimization algorithms to aid software system users: optimx for R. Journal of Statistical Software 43(9): 1-14.

- Kassambara A (2020) ggpubr: ’ggplot2’ Based Publication Ready Plots. R package version 0.4.0.

- Gohel D, Skintzos P (2023) flextable: Functions for Tabular Reporting. R package version 0.9.2.

- Jack CJ, Wiste H, Lesnick T, Weigand SD, Knopman DS, et al. (2013) Brain β-amyloid load approaches a plateau. Neurology 80(10): 890-896.

- Schindler SE, Li Y, Buckles V, Gordon BA, Benzinger TLS, et al. (2021) Predicting Symptom Onset in Sporadic Alzheimer Disease with Amyloid PET. Neurology 97(18): e1823-e1834.

- Yu L, Wang T, Wilson RS, Guo W, Aggarwal NT, et al. (2023) Predicting age at Alzheimer’s dementia onset with the cognitive clock. 19(8): 3555-3562.

- Li Y, Yen D, Hendrix R, Gordon BA, Dlamini S, et al. (2024) Timing of biomarker changes in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease in estimated years from symptom onset. Annals of Neurology 95(5): 951-965.

-

Marcela Cespedes, Timothy Cox, Cai Gillis, Nancy Nairi Maserejian, Hamid Sohrabi, Christopher Fowler, Paul Maruff, Stephanie Rainey-Smith, Colin Masters, Jurgen Mejan-Fripp and James Doecke. A Mathematically and Clinical Interpretable Approach to Identify Disease Sub-Groups from Longitudinal Patient Trajectories. Annal Biostat & Biomed Appli. 7(1): 2025. ABBA. MS.ID.000653. DOI: 10.33552/ABBA.2025.07.000653.

Longitudinal analyses; clustering; Alzheimer’s disease; logistic model; iris publishers; iris publisher’s group

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.