Research article

Research article

Prevalence of Toxoplasma Gondii in Sheep and Goats in Multan (Punjab), Pakistan

Mahnoor Khan Jamali1, Rida Tabbasum1, Abdul Latif Bhutto2, Sindhu2, Muhammad Ramzan3, Shah Jahan Musakhail3, Khalil-ur-Rehman3, Allah Bachaya, Faiza Habib3, Mammona Arshad1, Tayyba Awais1, Asfa Sakhawat1, Inayatullah Sarki2, Sahar Fatima1, Muhammad Fawad1 and Adnan Yousaf2*

1University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences Lahore, Pakistan

2Sindh Agriculture University Tandojam, Pakistan

3Department of Livestock and Dairy Development, Quetta, Pakistan

Adnan Yousaf, Sindh Agriculture University Tandojam, Pakistan.

Received Date: September 03, 2021; Published Date: October 05, 2021

Abstract

Toxoplasmosis, a protozoan illness caused by Toxoplasma (T.) gondii, is prevalent in humans and other animals, having been observed in a variety of nations and climates. There is no data on this element of food animals in Pakistan. The goal of this study was to find out how common T. gondii infection is in sheep and goats. A total of n = 300 serum samples from sheep (n =230) and goats (n = 170) were collected and tested for Toxoplasmosis using a commercial latex agglutination kit (Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd. Japan) in the Multan. Toxoplasmosis prevalence was 20.33% overall. Goats had a substantially greater P<0.01 prevalence 22.94% than sheep 16.92%, and females 30.55% had a significantly higher P<0.01 prevalence than males 16.92% for both species. Male sheep and goats were shown to be less seropositive to T. gondii in this investigation than female sheep and goats. Adult sheep had a considerably higher prevalence P<0.01 than younger animals. In both sheep and goats, the group aged 1–2 years is strongly seropositive compared to the group aged less than one year, followed by the group aged 2–3 years, and the group aged more than three years is least seropositive.

Keywords:Toxoplasma gondii; Sheep; Goat; Prevalence; Multan; Punjab

Introduction

Toxoplasmosis, an infection caused by the Apicomplexa protozoan Toxoplasma (T. gondii), is common in humans and other animals.

The disease has been documented in a wide range of countries and climates. Ingestion of sporulated oocysts, cyst-contaminated meats, especially from pig and sheep contact with free tachyzoites, or congenitally by trans placental transit infect intermediate hosts of the parasite [1]. Sheep and goats are more commonly infected with T. gondii in livestock, while infection in cattle has also been observed. This parasite is a leading cause of abortion in small ruminant breeders, resulting in large financial losses; infection does not normally cause clinical signs in cattle. Furthermore, goats infected with T. gondii are a major source of human infection due to the consumption of infected animals’ meat and milk [2]. Because goat milk consumption is higher among children with cow/buffalo milk allergies in certain rural parts of Pakistan, this information is vitally relevant for disease control and, more importantly, public health. According to recent research, only a small percentage of people infected with T. gondii obtain it through their uterus, while the majority get it from undercooked or raw meat harboring tissue cysts, oocysts shed by infected cats, or contaminated drinking water or fresh vegetables [3]. In many countries, T. gondii has been found in mutton and beef [4,5]. In Pakistan, there is no information on the prevalence of Toxoplasma infection in food animals. As a result, ensuring the presence of this parasite in animal species designated for human consumption is very beneficial. The purpose of this study is to determine the prevalence of T. gondii in sheep and goats in Multan; the findings may aid in the development of effective anti- Toxoplasmosis treatments for humans.

Methods and Materials

T. gondi had not been reported in Multan. In this study, n= 300 blood samples were obtained from mixed local breeds of sheep (n=130) and goats (n=170) in the urban region of Multan (Punjab), Pakistan, using a simple random sampling procedure between July 2020 and June 2021. Sera were extracted from 5 mL venous blood samples using a centrifuge at 2000g for 10 minutes and stored at -20 °C until needed. Sera were separated and tested for latex particle agglutination using a commercial kit (Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd., Japan) following the manufacturer’s protocol. In a U-shaped 96 well microtitration plate, latex agglutination buffer (25 μl) was applied to each well. In each well, 25 μl of diluted sera (1:8) was introduced and thoroughly mixed. Then, in each well, 25 μl of T. gondii-antigencoated latex beads were added. After a gentle shake, the plate was incubated at room temperature overnight. In comparison to the positive control, the agglutination pattern was examined (provided in the commercial kit). The information gathered was statistically examined [6].

Results and Discussion

Toxoplasmosis prevalence varies around the world, with rates ranging from 0% to 100% in different nations [7,8] depending on local customs, traditions, residents’ lifestyles, weather conditions, animal age, and husbandry practices [9]. Apart from that, the presence of cats that deposit oocysts, which after sporulation become infectious to humans and animals, may be linked to the prevalence rate [10]. Toxoplasmosis prevalence was 20.33% overall. It’s worth noting that the sampled area is Pakistan’s semi-arid zone, where fodder is scarce throughout the year and animals frequently become nutritionally deficient, increasing their vulnerability to infections. T. gondii is far less common in sheep than it is in goats. The increased prevalence rate in goats compared to sheep may be due to the goat population’s greater sensitivity to T. gondii infection. Previous research in Pakistan’s south-west region found that 2.5 percent of sheep and none of the goats tested positive for Toxoplasma antibodies [11]. The prevalence rate of 28.9 to 92% in Brazil [12,13] 42% in Germany [14], 59.8% in Bulgaria [15], and 80.61% in the Van region of Turkey [16] is lower than that observed by several authors in goats from various parts of the world. On the other hand, the current study’s prevalence rate was higher than the 19.3% infection rate observed in Iran [17] and the 5.9% prevalence rate found in the Lara State region of Venezuela [17]. [18,19] reported a prevalence rate of 23.7 percent in Iran and 3.2 percent in India [20] both lower than the prevalence rate established in the current study.

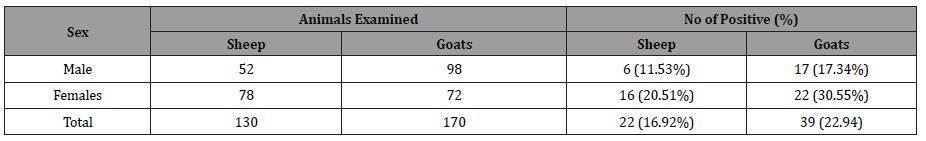

Because goats are commonly employed in rural parts of Pakistan, the current study’s high prevalence of Toxoplasmosis in goats is critically important for public health. T. gondii tachyzoites have been found in the milk of naturally infected goats [21], and a statistically significant link has been shown in the literature between positive T. gondii serology in humans and goat milk consumption [22]. The prevalence of Toxoplasmosis detected in sheep in this study was lower than that seen in other regions of Iran 22.5–35%, Turkey 33.2–55.6%, Ghana 33.2%, Greece 23%, Morocco 27.6%, Ethiopia 22.9%, Italy 28.4%, India 30%, and Canada 57.6% [17,19,23-31]. Various disparities in positivity between nations suggest that animals reared in these areas were exposed to varied levels of T. gondii oocyst contamination. It could also be related to the different procedures employed to monitor the T. gondii antibodies in each investigation. Contrary to our findings, sheep have a higher prevalence of Toxoplasmosis than goats in various parts of the world [17,23, 27, 30-33] the variation could be due to breed differences as the animals sampled were mixed local Female animals have been found to be more sensitive to protozoan infections than male animals [27,34]. Male sheep and goats were shown to have lower T. gondii positivity than female sheep and goats in this investigation (Table 1).

Table 1: Sex wise distribution of Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in sheep and goats

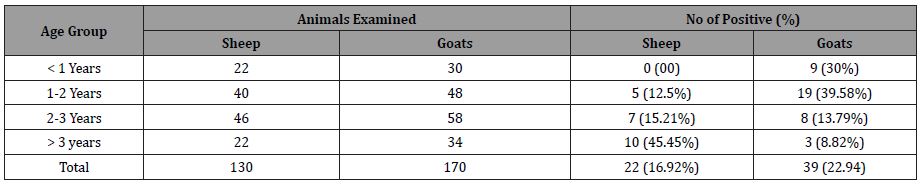

Table 2: Age wise distribution of Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in sheep and goats.

These findings are in line with those of a number of earlier investigations [26,35]. It is widely assumed that animals acquired Toxoplasma infection as they grew older by ingesting infective oocysts from the environment [27,36-37], as the chance for T. gondii exposure is seemingly abundant. The likelihood of an animal becoming exposed increases as it ages. As a result, animal age is thought to be a key factor in influencing the prevalence rate of Toxplasmosis in animals [38]. In both sheep and goats, the older are highly seropositive when compared to the groups of less than one year of age, 2–3 years of age, and 1–2 years of age, but the group of more than three years of age is least seropositive (Table 2).

It’s worth noting that all of the animals sampled were older than seven months and hence lacked maternal passive immunity. In the current investigation, no link was discovered between sheep and goats’ health and T. gondii infection positivity [39-41]. The majority of the animals identified positive appeared to be in good health and appeared to be normal. Furthermore, no link was discovered between T. gondii positive sheep and goats and companion animals such as dogs and cats. Cats undoubtedly play a key part in the transmission of Toxoplasmosis to humans, but food animals could potentially constitute a link in the chain of disease transmission to humans via raw milk and meat [2]. The significant seroprevalence of T. gondii antibodies reported in this study revealed that sheep in general, and goats in particular, had been exposed widely in District Multan. More research is needed to check food animals across the country [41-43].

Acknowledgements

Authors of this research are thankful to all farmers and farms staff for their support and cooperation in collection of sampling.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest for this research work.

References

- Pepin M, Russo P, Pardon P (1997) Public health hazards from small ruminant meat products in Europe. Rev Sci Tech 16(2): 415-425.

- Garcia VZ, Crus RR, Garcia GD, Baumgarten OH (2002) Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii infection in cattle, swine and goats in four Mexican states. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 17: 127–132.

- Ghazaei C (2005) Serological Survey of Antibodies to Toxoplasma. The Internet Journal of Veterinary Medicine 2.

- Jittapalapong S, Sangvaranond A, Pinyopanuwat N, Chimnoi W, Khachaeram W, et al. (2005) Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii infection in domestic goats in Satun Province, Thailand. Vet Parasitol 127(1): 17-22.

- Oncel T, Vural G (2006) Occurrence of Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in sheep in Istanbul, Turkey. Veterinarski Arhiv 76(6): 547-553.

- Steel RGD, Torrie JH (1992) Principles and procedures of statistics. McGraw Hill Book Co. Inc., New York, USA.

- Olivier A, Herbert B, Sava B, Pierre C, John DC (2007) Surveillance and monitoring of Toxoplasma in humans, food and animals: a Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Biological Hazards. The EFSA Journal 583: 1-64.

- Tenter AM, Heckerroth AR, Weiss LM (2000) Toxoplasma gondii: from animals to human. International Journal of Parasitology 30(12-13): 1217-1258.

- Smith JL (1999) Foodborne Toxoplasmosis. Journal of Food Safety 12: 17-57.

- Dubey JP (2004) Toxoplasmosis - a waterborne zoonosis. Veterinary Parasitology 126: 57–72.

- Zaki M (1995) Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in domestic animals in Pakistan. Journal of Pakistan Medical J Pak Med Assoc 45(1): 4-5.

- Bisson A, Maley S, Rubaire Akiiki CM, Wastling JM (2000) The seroprevalence of antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in domestic goats in Uganda. Acta Trop 76(1): 33-38.

- Ragozo AM, Yai L, Oliveira L, Dias RA, Dubey JP, et al. (2008) Seroprevalence and Isolation of Toxoplasma gondii from sheep from Sao Paulo State, Brazil. J Parasitol 94(6): 1259-1263.

- Seineke P (1996) seroprevaleze of antibodies against Toxplasma gondii in sheep, goats and pigs in Lower Saxony. Thesis, Dr. Vet. Med. Tierarztliche Hochschule, Hannover.

- Prelezov P, Koinarski V, Georgieva D (2008) Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii infection among sheep and goats in the Stara Zagora Region. Bulgarian Journal of Veterinary Medicine 11: 113-119.

- Karaca M, Babur C, Celebi B, Akkan HA, Tutuncu M, et al. (2007) Investigation on the Seroprevalence of Toxoplasmosis, Listeriosis and Brucellosis in Goats living in the region of Van, Turkey. Yyu Vet Fak Derg 18(1): 45-49.

- Hasemi Fesharki R (1996) Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in cattle, sheep and goats in Iran. Vet Parasitol 61(1-2): 1-3.

- Nieto SO, Melendez RD (1998) Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in goats from arid zones of Venezuela. J Parasitol 84(1): 90-91.

- Hamzavi Y, Mostafaie A, Nomanpour B (2007) Serological prevalence of toxoplasmosis in meat producing animals. Iranian Journal of Parasitology 2: 7-11.

- Sharma SP, Baipoledi EK, Nyange JF, Tlagae L (2003) Isolation of Toxoplasma gondii from goats with history of reproductive disorders and the prevalence of Toxoplasma and chlamydial antibodies. Onderstepoort J Vet Res 70(1): 65-68.

- Chiari CA, Neves DP (1984) Human toxoplasmosis acquired by ingestion of goat's milk. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 79(3): 337-340.

- Skinner LJ, Timperley AC, Wightman D, Chatterton JM, Ho-Yen DO (1990) Simultaneous diagnosis of toxoplasmosis in goats and goatowner’s family. Scand J Infect Dis 22(3): 359-361.

- Sharif M, Gholami S, Ziaei H, Daryani A, Laktarashi B, et al. (2007) Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in cattle, sheep and goats slaughtered for food in Mazandaran province, Iran, during 2005. Vet J 174(2): 422-424.

- Oncel T, Vural G, Babur C, Kilic S (2005) Detection of Toxoplasma gondii seropositivity in sheep in Yalova by Sabin Feldman Dye Test and Latex Agglutination test. Turkiye Parazitol Derg 29(1):10-12.

- Sevgili M, Babur C, Nalbantoglu S, Karas G, Vatansever Z (2005) Determination of seropositivity for Toxoplasma gondii in sheep in Sanliurfa province. Turkish Journal of Veterinary Animal Science 29: 107-111.

- Acici M, Babur C, Kilic S, Hokelek M (2008) Prevalence of antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii infection in humans and domestic animals in Samsun province, Turkey. Trop Anim Health Prod 40(5): 311-315.

- Puije WNA, Bosompem KM, Canacoo EA, Wastlaing JM, Akanmori BD (2000) The prevalence of anti-Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in Ghanian sheep and goats. Acta Trop 76(1): 21-26.

- Stefanakes A, Bizake A, Krambovites E (1995) Serological survey of toxoplasmosis. in sheep and goats on Crete. Bulletin of the Hellenica Veterinary Medical Society 46: 243-249.

- Sawadogo P, Hafid J, Bellete B, Sung RT, Chakdi M et al. (2005) Seroprevalence of T. gondii in sheep from Marrakech, Morocco. Veterinary Parasitology 130: 89-92.

- Bekele T, Kasali OB (1989) Toxoplasmosis in sheep, goats and cattle in central Ethiopia. Vet Res Commun 13(5): 371-375.

- Masala G, Porcu R, Madau L, Tanda A, Ibba B (2003) Survey of ovine and caprine toxoplasmosis by IFAT and PCR assays in Sardinia, Italy. Vet Parasitol 117(1-2):15-21.

- Mirdha BR, Samantaray JC, Pandey A (1999) Seropositivity of Toxoplasma gondii in domestic animals. Indian J Public Health 43(2): 91-92.

- Amin AM, Morsy TA (1997) Anti-Toxoplasma antibodies in butchers and slaughtered sheep and goats in Jeddah Municipal abattoir, Saudi Arabia. J Egypt Soc Parasitol 27(3): 913-918.

- Alexander J, Stinson WH (1988) Sex hormones and the course of parasitic infection. Parasitology Today 4(7): 189-193.

- Ntafis V, Xylouri E, Diakou A, Sotirakoglou K, Kritikos I, et al. (2007) Serological survey of antibodies against Toxoplasma gondii in organic sheep and goat farms in Greece. Journal of the Hellenic Veterinary Medical Society 58: 22-33.

- Figueiredo JF, Silva DAO, Cabral DD, Mineo JR (2001) Seroprevalnce of Tixoplasma gondii infection in goats by the indirect heamagglutination, immunofluorescence and immunoenzymatic tests in the region Uberlandia, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 96(5): 687-692.

- Figliuolo LPC, Rodrigues AAR, Viana RB, DM Aguiara, N Kasaia, SM Gennar (2004) Prevalence of anti-Toxoplasma gondii and anti-Neospora caninum antibodies in goat from Sao Paulo State, Brazil. Small Ruminant Research 55(1-3): 29-32.

- Dumetre A, Ajzenberg D, Rozettea L, Mercier A, Darde ML (2006) Toxoplasma gondii infection in sheep from Haute-Vienne, France. Veterinary Parasitology 142: 376-379.

- Anonymous (2006) Livestock census (Punjab Province), Govt of Pakistan. Pp. 4-58.

- Gaffuri A, Giacometti M, Tranquillo VM, Magnino S, Cordioli P, et al. (2006) Serosurvey of roe deer, chamois and domestic sheep in the Central Italian Alps. J Wildl Dis 42(3): 685-690.

- Rodriguez PE, Molina JM, Hernandez S (1995) Seroprevalence of goat toxoplasmosis on Grand Canary Island (Spain). Preventive Veterinary Medicine 24(4): 229-234.

- Vesco G, Buffolano W, La Chiusa S, Mancuso G, Caracappa S et al. (2007) Toxoplasma gondii infections in shepp in Sicily, southern Italy. Vet Parasitol 146(1-2): 3-8.

- Waltner Toews D, Mondesire R, Menzies P (1991) The seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in Ontario sheep flocks. Can Vet J 32(12): 734-737.

-

Tayyba Awais, Asfa Sakhawat, Inayatullah Sarki, Sahar Fatima, Muhammad Fawad, Adnan Yousaf etc al.. Prevalence of Toxoplasma Gondii in Sheep and Goats in Multan (Punjab), Pakistan. Arch Animal Husb & Dairy Sci. 2(4): 2021. AAHDS.MS.ID.000541.

-

Toxoplasma gondii; Sheep; Goat; Prevalence; Multan; Punjab, infection, Toxoplasma antibodies.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.