Case Report

Case Report

Mange in an Adult Domestic Short Haired Cat-Case Report

Wyckliff Ngetich, Department of Clinical Studies, Egerton University, Egerton, Kenya.

Received Date: August 05, 2019; Published Date: August 21, 2019

Abstract

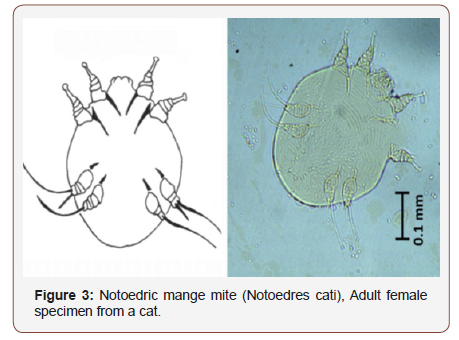

Notoedric mange is a common parasitic skin condition in cats. Notoedres cati is a burrowing mite that infest cats and the clinical manifestations start from the head and spreads throughout the body. Owners’ complaints are usually alopecia, lethargy and inappetance. The case presented here is of an adult shorthaired cat presented at the small animal clinic for management of skin condition. Hair plucking and microscopic examination revealed somewhat oval shaped parasites with two forelimbs extending beyond the body with the two hinds not projecting beyond the body margin. These are characteristic features of Notoedres cati. Blood smear showed toxic granulations and lymphocytic intracytoplasmic inclusions. A diagnosis of a co-infection of mange and Erlichiosis was therefore made. Management of the case was initiated immediately with fluid therapy, Ivermectin and Imidocarb diproprionate but it succumbed on the night of the third day. Early diagnosis of parasitic infections in cats is essential for proper and appropriate management and control.

Keywords: Cat; Mange; Ehrlichia; Management

Introduction

Mange is a persistent skin condition of mammals caused by infestation with parasitic mites [1]. Mites are tiny arthropods, usually less than 1 mm in length and difficult to see with the naked eye [1]. Adult mites have eight legs, and larvae have six. The effect of the mites on the animal’s skin (mange) is the most visible sign of an infestation [2]. Several skin conditions commonly caused by parasitic mites in domestic animals include sarcoptic, notoedric, demodectic, otodectic, and psoroptic mange [3]. Of these forms of mange, only sarcoptic and notoedric mange are caused by female mites burrowing in the skin [1]. Sarcoptic mange commonly occurs in dogs and notoedric mange in cats [2].

The adult female notoedric mite burrows in the skin and deposits eggs, which hatch after three to four days [3]. The entire life cycle from egg to adult takes 6–10 days. The females also may invade hair follicles or sebaceous glands and lay eggs [2]. The common symptoms of mange are redness and itching of the skin and hair loss. The irritation of the skin is due to an allergic response to molecules associated with the mite’s bodies, secretions (e.g., saliva), and fecal material [1,4]. Skin scrapings or hair plucking aid in diagnosis of mange in companion animals. The case presented here is of an adult female cat brought to veterinary clinics for weakness, progressive body weight loss and abnormal skin lesions.

Case History

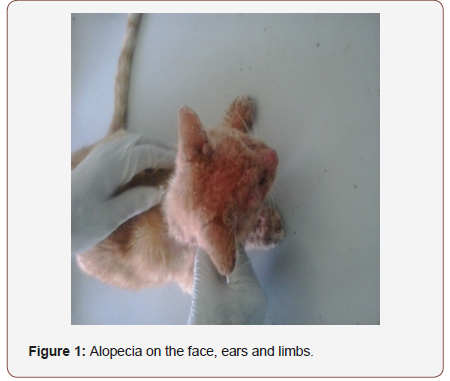

An adult, female Domestic Short Haired cat was brought to the University of Nairobi, Small Animal clinic with a history of alopecia, lethargy and body weight loss for almost a month. On presentation, the cat was in poor body condition, scratching against objects (pruritus), alopecic area on pinnas of the ears and head Figure 1, the neck, shoulders, back and the limbs and hyperemic muzzle. Clinical examination revealed severe dehydration, thickened and wrinkled skin of the alopecic areas; crusts and some parts were moist Figure 2. The mucous membranes were pale, capillary refill time of more than 2 seconds and a temperature of 39.6°C, heart rate of 120 beats per minute, respiration of 32 breaths per minute. The hair was loose and easily fell off. Skin scrapings revealed parasites with roughly circular outline, long and unsegmented pedicel, four pairs of legs with the 3rd & 4th pairs not projecting beyond the margin of the body similar to what has been describe by Butler Figure 3. A blood smear revealed toxic granulations and intracytoplasmic inclusions in the lymphocytes (morullae). Diagnoses of mange and Erlichiosis were made (Figure 1-3).

Management

Rehydration was done with warm 100ml Lactated Ringer’s solution subcutaneously. She was also given 1.2mg Ivermectin (Ivermet® 1% w/v by Metrovet Kenya Limited) and 24mg Imidocarb dipropionate (imizol® 12% w/v by Vet Pharma Friesoythe GmbH) and admitted for further management. The following day, she showed slight improvement but was still dehydrated and had pale mucous membranes. The condition worsen on the third day, with subnormal temperature, 37.8°C, Heart Rate of 96 beats per minute, very pale mucous membranes, closed eyes with swollen eyelids, severe dehydration with uncoordinated movements. Auscultation revealed harsh lung sounds with faint heartbeats. Intravenous catheter was placed and a total of 100ml Lactated Ringer’s solution given and 6 mg dexamethasone administered to relief shock and 50mg Enrofloxacin (Enroflox-150® by Interchemie), given intramuscularly and 2ml EDTA blood collected for hematology. The cat died at night of the third day and the owner was not willing for postmortem to be carried out.

Discussion

Notoedric mange is a highly contagious mite infection caused by Notoedres cati in the skin of domestic and wild cats [1]. It is the most common mite of domestic cats in North America, Europe, and Africa [3]. This mite has also been isolated from rats, squirrels, rabbits, and bats [5]. Notoedric mites rarely infest dogs or other canids, but they occasionally and temporarily infest humans [4]. Even under a microscope, these mites appear very similar to the sarcoptes mites, but there are differences that can be used to tell the two apart using a compound microscope and identification keys [1]. It is smaller than sarcoptes and its anus is on the dorsal surface instead of the posterior margin of the body. Notoedric cati occurs chiefly on the ears, & back of the neck, but may extend to the face, foot, hind paws & in young cats, to the whole-body Mullen GR and Connor BMO [1] which is similar with the manifestations in this case. The skin reaction in the animal is caused by the presence of the mites and their excrement in the burrows [3]. The first symptoms usually appear three weeks after the animal becomes infested, although the delay decreases with repeated exposures. Symptoms of notoedric mange usually begin on an animal’s head, the ears, face, neck and shoulders and then spread across the entire body Walker et al. 1994. This description concurs with the signs manifested in this particular case. The irritation is intense; the skin becomes itchy, with reddening, scaling, hair loss and formation of gray/yellow crusts [3]. The infested skin becomes thick, folded, and wrinkled. The irritation causes the animal to scratch, resulting in removal of skin and further irritation. This case was a chronic case because it has been there for more than a month and it agrees with what Soulsby EJL [4] reported that chronic Notoedric mange may lead to debilitation and death.

The burrowing mites cause the skin to ooze serum, which dries and forms crusty scabs. Scratching spreads the infestation and often leads to secondary infection of wounds. These infections cause the unpleasant odor often associated with “mangy” animals. Infested animals may suffer from weight loss, lack of appetite, and poor hearing and vision [1]. Ear mange, caused by the otodectic ear mite, is common among cats and dogs [3]. The mites also infest the ears of other carnivores such as foxes and raccoons. All of the otodectic mite’s life stages are found within the ear canal, though in some cases otodectic infestations can spread beyond the ear to the rest of the body, particularly the head, tail, and feet [3]. Otodectic mites do not burrow into the skin, living instead on skin surfaces deep inside the external ear canal. These mites feed primarily on skin but occasionally pierce the skin to feed on blood, serum, and lymph [4].

Psoroptic mange mites occur in the ears of domestic and wild animals, particularly rabbits [3]. These ear mites do not burrow but instead feed on skin tissue, which irritates the skin and causes lesions [1]. The lesions produce scabs, and the scabs protect the mites from the environment and shield them from removal by the animal when it scratches [4]. It manifests as scratching, shaking its head, losing its balance, and tensing its neck muscles [3]. The infestation may spread to other parts of the body, and the lesions may become infected with bacteria [4]. Mange-causing mites spread through direct contact from infested to non-infested animals; however, the development and severity of mange will depend upon the type of mite and the animal’s health [3].

Temporary animal mange may be contracted by the owners and handlers of infested animals, although this is typically limited to the burrowing mites that cause sarcoptic and notoedric mange [1]. Humans are not appropriate hosts for these mite species, and infestations in humans are short-lived because the mites do not form burrows or reproduce in human skin. When a cat or dog is treated, any reactions in humans who have contact with the animal will clear up quickly [1]. Diagnosis of incriminated mites species in companion animals involve species affected (species specificity), clinical manifestation of the condition and microscopic examination for confirmation and therefore this diagnosis was made based on the above principles. The treatment options of mite infestation in cats involve a number of steps. One is removing the scabs and debris with mild shampoo followed by application of 2-3% lime sulphur dip weekly for 6-8 weeks. Two topical selamectin applications can also be done 4 weeks apart to treat Notoedric mange in cats [6].

The mixed infection with Erlichia bacteria may have worsen the prognosis since it affects the immune system of the animal by attacking granulocytes (Lymphocytes and Neutrophils) that play an important role as the line of defense [7,8]. Ehrlichia canis (E. canis) and Ehrlichia risticii (E. risticii) are believed to be the primary causative agents in the cat [9]. They enter various cells of the body and behave as tiny parasites, morullae, eventually killing the cell [10]. Ehrlichiosis has been detected in cats in the United States, Europe, South America, Africa, and the Far East [7,8]. It manifests as Lethargy, depression, anorexia Adaszek L, et al. [7], weight loss, vomiting and diarrhea Heikkilä HM, et al.[8], fever, pale mucous membranes from anemia Bown KJ, et al. [9], breathing difficulty, swollen glands (enlarged lymph nodes), swollen and inflamed joints and discharge from the eyes and inflammation inside the eyes [10]. These signs overlap with those shown by Mange and the co-infection might have complicated this case and led to death.

Conclusion

Mange in cats can be fatal especially in case of co-infection with an immune-compromising condition such as Erlichiosis. Therefore, control of ectoparasite is essential to control parasitic and tickborne infections.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflicts of interest.

References

- Mullen GR, Connor BMO (2009) Mites (Acari). In: Mullen GR, Durden LA (eds.), Medical and Veterinary Entomology, Elsevier, USA, pp: 433-492.

- Whitlock JH (2003) Diagnosis of Veterinary Parasitism. Lea & Febiger, USA.

- Weeks ENI, Kaufman PE (2003) Mange in Companion Animals, University of Florida press, USA, pp: 289.

- Soulsby EJL (2000) Helminths, Arthropods & Protozoa of Domesticated Animals. 7th (edn), England.

- Gakuya F, Rossi L, Ombui J, Maingi N, Muchemi G, et al. (2011) The curse of the prey: Sarcopetes mite molecular analysis reveals potential prey-to-predator parasitic infestation in wild animals from Maasai Mara, Kenya. Parasites & Vecors 4: 193.

- Emily Rothstein (2011) Notoedric Mange. Saunders, an imprint of Elsevier Inc.

- Adaszek L, Górna M, Skrzypczak M, Buczek K, Balicki I, et al. (2012) Three clinical cases of Anaplasma phagocytophilum infection in cats in Poland. J Fel Med and Surg 5: 34-39.

- Heikkilä HM, Bondarenko A, Mihalkov A, Pfister K, Spillmann T (2010) Anaplasma phagocytophilum infection in a domestic cat in Finland: Case report. Acta Veterinarie Scandinavia 52: 62.

- Bown KJ, Lambin X, Ogden NH, Begon M, Telford G, et al. (2009) Delineating Anaplasma phagocytophilum ecotypes in coexisting, discrete enzootic cycles. Emerg Infect Dis 15(12): 1948-1954.

- Cruz AC, Zweygarth E, Ribeiro MF, Da Silveira JA, De la Fuente J, et al (2012) New species of Ehrlichia isolated from Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus shows an ortholog of the E. canis major immunogenic glycoprotein gp36 with a new sequence of tandem repeats. J Parasit Vect 5: 291.

-

Ngetich Wyckliff. Mange in an Adult Domestic Short Haired Cat-Case Report. Arch Animal Husb & Dairy Sci. 1(4): 2019. AAHDS. MS.ID.000520.

-

Cat, Mange, Ehrlichia, Management, Domestic, Parasitic skin, Skin, Infections, Sarcoptic, Notoedric, Demodectic, Otodectic, Irritation

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.