Review Article

Review Article

Dairy Production and Milk Consumption in Pastoral Areas of Ethiopia

Ignacio Ciampitti1, Mary Challender1 and Jim Gaffney*2

1Department of Agronomy, Kansas State University, USA

2Department of Agricultural Science, USA

Corresponding AuthorTewodros Alemneh, Woreta City Office of Agriculture and Environmental Protection, South Gondar Zone, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia, Email:tedyshow@gmail.com

Received Date: October 10, 2019; Published Date: October 22, 2019

Abstract

Dairying is one of the livestock production systems practiced in almost all over the world including Ethiopia, involving a vast number of small, medium, or large sized, subsistence or market-oriented farms. Pastoral communities are acutely aware of the nutritional value of milk. In pastoral area, milk from camels and goats, is the most beneficial for children’s overall health, strength and growth. In the wet season, milk consumed by pastoral children can account for 67% of the mean daily energy they require and 100 % of their protein requirements. However, due to lack of availability and access to milk in the dry season, daily milk consumption decreases in pastoral areas. In view of such a large number of dairy cows and the important number of producers engaged in the dairy sector, the development efforts so far made have not brought a significant impact on the growth of the sector. The milk marketing system is not-well developed giving the large majority of smallholder milk producers, limited access to the market. In most of the cases, existing dairy cooperatives are operating in areas that are accessible to transportation and markets. This means that a substantial amount of milk does not reach to markets and a number of producers keep on producing at a subsistence level. Therefore, this review focuses on the dairy production and milk consumption practices in pastoral areas of Ethiopia.

Keywords: Pastoral communities; Milk; Dairy cows

Introduction

Ethiopia holds large potential for dairy development due to its large livestock population, which comprises 60.3 million cattle, 31.3 million sheep, and 32.7 million goat populations [1]. There are about 10 million dairy cows in Ethiopia producing approximately 3.2 billion liters on average of 1.54 liters per cow per day over a lactation period of 180 days [2]. The farm-level value of the milk is an estimated Birr 16 billion. Estimated calf consumption and wastage of milk is 32% of the milk produced [3].

Dairy production is one of the livestock production systems practiced throughout the world including our country Ethiopia, involving a vast number of small, medium, or large-sized, subsistence or market-oriented dairy farms. Based on climate, landholding and integrated with crop production; dairy production can be; classified into pastoralism, highland smallholder, urban and peri-urban and intensive dairy farming system are recognized in Ethiopia. There are over six distinguishable, indigenous cattle breeds in Ethiopia; mainly Arsi, Barca, Boran, Fogera, Horro, and Ogaden are evolved as a source of natural selection [4].

In the pastoral area of Ethiopia, livestock owners who exploit natural grasslands mainly in the arid areas; the herd is dominating with unimproved Zebu animals and milk production is of subsistent type. It is mainly operating in the rangelands where the peoples involved follow animal-based lifestyles, which requires them to move from place to place seasonally, based on feed and water availability. Livestock doesn’t provide inputs for crop production but they are the very backbone of their owners providing all of the consumable and saleable outputs and regard as insurance against adversity, milk production is dependent on season due to the rainfall pattern that influenced feed availability [5]. The main objective of this review paper is to review; dairy production and milk consumption trends in the pastoral area of Ethiopia.

Milk and Milk Product Consumption in Pastoral Areas

Women in Somali Region get milk from different species like camel and goat to be the most beneficial for children’s overall health, strength, and growth. During the rainy season, milk consumed by pastoral children can account for 67% of the mean daily energy they require and 100% of their protein requirements [6]. Lack of availability and access to milk in the dry season decreased daily consumption amounts by almost 25% with milk contributing only 16% and 50% of energy and protein requirements respectively. In dry season, children’s milk consumption will drop an average of 50% [7].

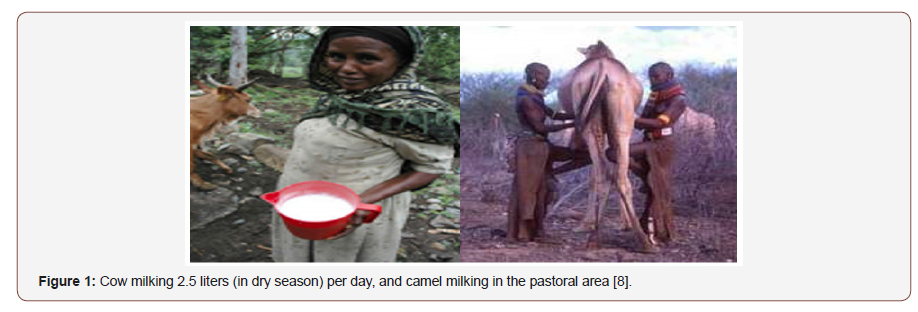

Households are estimated to collect 5 liters (wet season) and 2.5 liters (dry season) of cattle milk and 13 liters (wet season) and 8 liters (dry season) under this production system [6]. Camel milk is cited as being more important for household food security because the lactation period extends longer into the dry season with a total average lactation period of 9 months. However, in most pastoralist cultures, camels are not an asset commonly held by poorer households [7,8] (Figure 1).

Livestock owners who exploit natural grasslands mainly in the arid areas, even though information on both absolute numbers and distribution is varied, it estimated that about 30% of the livestock populations are found in the pastoral areas [9]. The herd is dominating with unimproved Zebu animals and milk production is of subsistent type. It is mainly operating in the rangelands where the peoples involved follow animal-based lifestyles, which requires them to move from place to place seasonally, based on feed and water availability [9].

Livestock production in pastoral areas system that supports an estimated 10% of the population covers 50-60% of the total area mostly lying at altitudes ranging from below 1500 m.a.s.l, is the major system of milk production in the low land. However, because of the rainfall pattern and related reasons shortage of feed availability milk production is low and highly seasonally dependent. In this system indigenous stock grazing in pastures in extended rangeland throughout the year and milked twice a day. No supplementary feeding is provided [9].

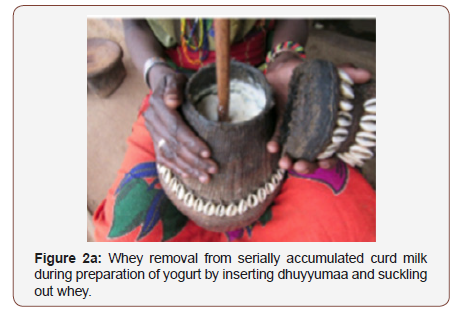

Borana is a pastoral area in southern Ethiopia where milk is a common food. The observation of milk handling and processing practices revealed apparent unhygienic conditions and high pathogen loads. Pastoral women considered proper smoking of containers and utensils, using various plant species, as an important traditional practice for assuring the quality and safety of milk and dairy products. Other reasons for smoking mentioned are increased shelf-life of products, good consistency of curdled milk, and pleasing flavor and health benefits [9] (Figure 2a,2b).

The pastoral and agro-pastoral communities have different animal resources and stockbreeding complex. The prevailing ones are the cattle-sheep and camel-goat complexes. The cattle-sheep complex is characterized by grazing and reared in the grassland, whereas camel goat complex is characterized by the browsing of trees and shrubs. The livestock resources and stock-breeding complex has a direct relation with milk production and productivity. Analysis of livestock resources and stock-breeding complex of the Borana Zone is considered to take advantage of this [9,10].

Milk production from milking animals (Cattle, camels, sheep and goats) is influenced by their population and distribution, and the availability of natural pasture and water. Besides, types of animal breeds, the composition of milking animals in herd are one of the most important factors influencing milk production in the pastoral systems. The milk production also directly correlated with the environmental situation. The better the environment/climate the better is the milk production and vice versa [9].

The animals milking frequency per day varies based on the type of livestock species and seasonal calendars of the year. In addition to this traditionally newly birth gave animals are not milked up to 2 to 3 weeks until the calves getting more milk and colostrum which helps to develop immunity and to get stronger. In wet season, where forage and water are relatively available, lactating cows are milked twice a day during early in the morning before grazing time and evening after grazing. Traditional cows that lost their calf due to death will not be milked even though they are able to supply milk. On the other hand, during prolonged dry periods where feed and water are highly scarce, the pastoralists do not milk the lactating cows rather focusing on cows and calves live-saving as much as possible [9].

Quantity of milk produced

Out of the total cattle population in Borana pastoralists, the mature female animals kept for milk production are identified and it is found to be 38.42% and of these about 60% assumed is milk-producing animals annually [10]. Besides this proportion the productivity of milk i.e. milk liter/ animal /day is also identified ranges between 0.5 litters and 2.5 litters and an estimated average of 1.5 litters/cattle are taken. The lactation length also ranges between 120 to 270 days based on availability of feed and water as well as length of dry seasons and an average of 180 days is considered [10].

Most pastoralists did not follow milking procedure during milking, had no appropriate and permanent milking place they are moveable place to place, most of the pastoralists do not milk animals on treatment, did not wash hands before and after milking, did not cover the milk and had no potable water for washing hands and milking materials. Moreover, some of the pastoralists deliver mastitis milk to the consumer and use poor facilities for drying container. Tying of the tail is important in the local setting because cows carry a lot of dust or mud from the stable on their bodies. During milking, a lot of this dust is dislodged by the constant waving of the tail to driveway flies. This constitutes one of the most direct methods of milk contamination [11].

Milk products

The pastoralists and agro-pastoralists of the Borana Zone have been doing a traditional milk processing practices at the household level and produces butter, skimmed milk, yoghurt and Ayib particularly from cow’s milk. Borana pastoralists produce milk products like butter to cope the problem of short shelf life of fresh milk. This is because the fresh milk will not stay fresh in some areas even until they reach to the market hence, they are forced to process it to butter to cope with the risk of Perishability. The study revealed that the more the pastoralists are far from the market they tend to process the milk and produce butter [12].

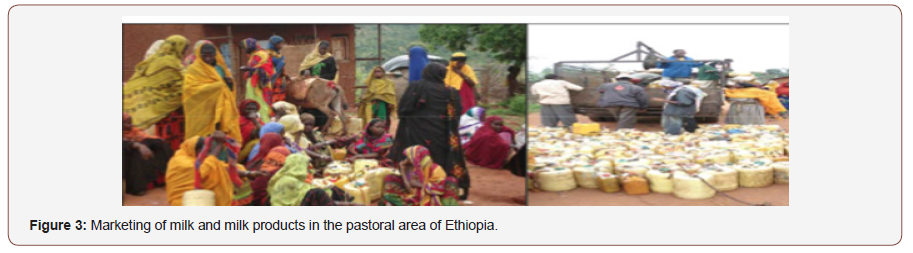

Women and milk marketing in the pastoral areas of Ethiopia

Milk and milk product marketing is entirely done by the women in Borana pastoral area. Not only milk and milk product marketing but also the management of these products at home is exclusively the responsibility of women. Women have decision power on milk and milk product-related activities. Most of milk traders in pastoralist markets are women, showing how all activities related to milk is exclusively left for women. Therefore, improving milk and milk product marketing has great implication in economically empowering women in Borana pastoral areas [12] (Figure 3).

Overall goal of the intervention on the milk and milk subsector value chain is to reduce poverty in the pastoral community of Borana. On average about 73.5% of the pastoral population constitutes destitute and poor wealth category. Out of which 38.7 are destitute with no livestock and milking animals and the remaining balance 61.2 % are poor pastoralists who have 1-5 livestock. During the data analysis the poor have at least 1 milking cow in the year. The poor produce milk expensively than the middle, rich and very rich wealth category pastoralists [12].

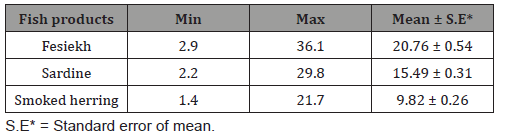

Accordingly, the poor cost Birr 0.79 per which is 33% greater than the cost spent by the middle category, 29.5% than the rich and 92% than the very rich wealth category. This implies that the poor get lower margin than the other wealth category fellow pastoralists. In view of that the poor pastoralists get 14% less margin than the middle group, 12.5% less than the rich and 26.5% less than what the very rich category gains. This means poor women earn fewer margins from milk sales than the middle, rich and very rich pastoral women categories. Hence interventions based on wealth category have to be appreciated at all levels to attain livelihood improvement to those poor target groups [13,14] (Table 1).

Table 1: Plant Spices used in the Preparation of Metata Ayib in Ethiopia.

Conclusion

Ethiopia has the highest livestock populations in Africa and accounts for 17% of cattle, 20% of sheep, 13% of goats and 55% of equines in Sub-Saharan Africa. Livestock production in Ethiopia is mainly of smallholder farming system with an animal having multipurpose use and accounts for approximately 30% of the total agricultural Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and 16% of national foreign currency earnings. Pastoral women have no awareness of milk-borne diseases. Instead, they emphasized on the advantages of consuming raw milk. Milk-related health problems are mentioned only a few times, and these are mostly not directly related to microbiological safety. This can be either due to the adaptation of the local communities to unhygienic raw milk consumption or the presence of effective risk mitigation strategies.

Acknowledgement

Authors most gratefully thank Debre Berhan University staffs and the Communities at large.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare that no conflicts of interests.

References

- CSA (2018) Agricultural Sample Survey 2016/2017: Report on Livestock and Livestock Characteristics (private peasant holdings) Addis Ababa Ethiopia 2: 9-13.

- Tefera TL, Puskur R, Hoekstra D, Tegegne A (2010) Commercializing dairy and forage systems in Ethiopia: An innovation systems perspective. Improving Productivity and Maket Success (IPMS) of Ethiopian Farmers, pp. 17.

- Berhanu A, Tsehayneh G (2014) Fermented Ethiopian Dairy Products and Their Common Useful Microorganisms: A Review. World Journal of Agricultural Sciences 10(3): 121-133.

- Tadesse G, Mengistie A (2016) Challenges, Opportunities, and Prospects of Dairy Farming in Ethiopia: A Review. World Journal of Dairy & Food Sciences 11(1): 1-9.

- Zegeye WW (2003) Imperative and challenges of dairy production, processing and marketing in Ethiopia. In: Y Jobre & G Gebru(eds), Challenges and opportunity of livestock marketing in Ethiopia. Proceeding of the 10 annual conferences of the Ethiopian Society of animal production (ESAP), Ethiopia, pp. 61-67.

- Sadler and Catley (2009) Milk Matters: the role and value of milk in the diets of Somali pastoralist children in Liben and Shinile, Ethiopia.

- Land O Lakes (2011) The next stage in dairy development for Ethiopia Land O’Lakes, Ethiopia.

- Hussen K, A. Tegegne MY, Kurtu B Gebremedhin (2008) Traditional cow and camel milk production and marketing in agro-pastoral and mixed crop-livestock systems: The case of Mieso Diestice, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. Improving Productivity and Maket Success (IPMS) of Ethiopian Farmers Project, Ethiopia, pp. 1-58.

- Getachew F, Geda G (2001) The Ethiopian dairy development policy: A draft policy document. Food and Agriculture Organization, Ethiopia.

- HussenK, Tegegne A, Yousuf M, Gebremedhin G (2008) Cow and camel milk production and marketing in agro pastoral and mixed crop livestock system. A paper presented on conference of international research on food security, natural resource management and rural development. Europe, pp. 1-4.

- Abraha S, Belihu K, Bekana M, Lobago F (2009) Milk yield and reproductive performance of dairy cattle under smallholder management system in north-eastern Amhara region of Ethiopia. Trop Anim Health Prod 41(7): 1597-1604.

- Patrice G, Mohamed LS, Nelly G (2007) An evaluation of milk quality in Uganda: Value chain assessment and recommendations. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development 7(5): 1-16.

- Zegeye WW (2003) Imperative and challenges of dairy production, processing and marketing in Ethiopia. In: Y Jobre & G Gebru (eds): Challenges and opportunity of livestock marketing in Ethiopia. Proceeding of the 10 annual conferences of the Ethiopian Society of animal production (ESAP), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, pp: 61-67.

- Tsehai GK, Amiha, Berhanu A (2013) Microbial profile of metata (fermented cheese) and the role of spices as an antimicrobial agent against spoiling microorganisms in traditional fermentation process. Ethiopia, pp. 1-34.

-

Mebrate Getabalew, Tewodros Alemneh. Dairy Production and Milk Consumption in Pastoral Areas of Ethiopia. Arch Animal Husb & Dairy Sci. 1(5): 2019. AAHDS.MS.ID.000522.

-

Pastoral communities, Milk, Dairy cows, Strength, Growth, Environment, Treatment

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.